The Kerala High Court upholds a government order to shut down a school that admitted only Muslim students and imparted exclusive religious instruction

By NV Ravindranathan Nair in Thiruvananthapuram

On August 2, 2017, the Kerala government ordered the closure of a school run by the Hidaya Educational and Charitable Trust based in Thiruvananthapuram. The school was ordered to be shut following reports that only students belonging to a particular community were being enrolled there for studies. The Trust approached the Court, challenging the state government’s decision to close down the school for allegedly promoting exclusive religious instruction.

In a significant judgment, the Kerala High Court ruled that in a pluralistic society like India which accepts secularism as the basic norm in all spheres, including education, schools must desist from imparting religious instruction in only one religion while excluding all other faiths.

Justice Muhamed Mustaque upheld the closure of the school which admitted only Muslim students, saying the institution imparted religious instruction exclusively for Islam, something that cannot be allowed. While disposing of the writ petition, the Court observed that cultural rights, as protected under Article 29, would include nature of education as well. “The state government can initiate action for closure and de-recognition of the schools if they are found violating the order. No school, which is required to have recognition under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, is entitled to impart religious instruction or religious study of one religion exclusively in preference to other religion,” the Court ordered.

It, however, said that private schools could provide religious instruction keeping in mind religious pluralism. “A private school which requires recognition is entitled to impart religious instruction or study based on religious pluralism after obtaining permission from the state government,” the ruling said. “Our Constitution accords special protection to the minorities under Article 25, Article 29 and Article 30. Cultural rights, as protected under Article 29, would include nature of education as well. The right to establish and administer educational institutions under Article 30 would also include the right to choice of education, subject to any restriction imposed under law,” the order read.

However, these rights do not extend to dilute the secular nature of education, it added. “These rights cannot override the basic values of the Constitution. It can be exercised only in consistent with the fundamental values of the Constitution. The status of minority institutions in relation to imparting elementary education is relatable to state function. Minority institutions, therefore, cannot shrug off their role as state functionaries and protect sectarian education under the garb of Articles 29 and 30,” it further said.

The Court, while deciding the fate of the writ petition considered it against the backdrop of declaring right to elementary education a fundamental right under Article 21A of the Constitution and the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009. “Do private unaided schools which require State recognition have the right to promote a particular religion to the exclusion of other religions while imparting elementary education?” it observed and went on to examine the matter in detail.

The government had stated that the school was functioning without recognition or CBSE affiliation and had admitted more than 200 students, all of them Muslims. Acting on intelligence reports, the government ordered its closure. It noted that admission was being given exclusively to children from Muslim families. The Deputy Director of Education (DDE), Kerala government, then issued the order to close down the school. The DDE, who conducted the inspection, found that the syllabus was in accordance with the curriculum prescribed by Millet Foundation Education Research and Development (MFERD), a Hyderabad-based organisation.

The Court observed that on browsing the website of the Foundation, it was seen that the portal was providing a common platform for Muslim educational institutions for sharing, networking, co-ordinating and co-operating among themselves, to complement the efforts of individuals, professionals and organisations to achieve excellence in the field of education within the boundaries of the Islamic Shariah. “Our aim is to address various challenges faced by Muslim educational institutions and find solutions through collaboration, research and development. One of our major objectives is to provide quality education by formulating and designing a value-based curriculum for schools to nurture and culture our future generations with Etiquettes (tarbiyat), Education (taleem) and Excellence (miyaar),” claims MFERD.

The Court observed that it clearly showed that apart from achieving excellence in temporal education, an attempt was being made to promote the individual identity of the pupil based on the Islamic Shariah which would necessarily be possible only by imparting religious instruction in institutions.

It went on to talk about the role of educational institutions, saying “the role of educational institutions which require recognition under the RTE Act, therefore, must be to promote constitutional values to shape the character of the pupil based on fundamental values of the Constitution, and not by denouncing it. Thus, educational institutions can impart religious instruction or study based on religious pluralism instead of exclusivism.”

Under Article 28(1) of the Constitution, there is a complete embargo on educational institutions run wholly out of State funds imparting religious instruction. However, the Constitution does allow educational institutions having State recognition or using funds from the State to give religious instruction with the consent of the guardian [Article28(3)]. This enables educational institutions to give religious instruction to minor students with the consent of the guardian.

The Court emphasised the need to keep in mind the fact that this enabling clause existed in the Constitution at a time when elementary education was yet to be declared a fundamental right. Further, this does not enable schools to give religious instruction of one religion to the exclusion of other religions.

“The Supreme Court in Ms Aruna Roy and Others vs Union of India and Others [(2002) 7 SCC 368] did not negate religious education based on religious pluralism but it cautioned against religious education based on religious exclusivism. There exists a substantial distinction between religious instruction and religious study. The embargo in the Constitution is on educational institutions imparting religious instruction. There is no embargo on educational institutions imparting religious study in the Constitution,” the judgment said.

“Exclusivism in religious study, if promoted by educational institutions will, therefore, have to be tested against the backdrop of the secularist ideal of the Constitution. The Constitution nowhere permits to impart exclusive religious instruction or study. It is in this background that the issue in this writ petition subsequent to the incorporation of Article 21A, which declares right to education as a fundamental right among children in the age group of 6 to 14, will have to be considered,” the Court said.

The Court further noted that Parliament, on realising the threats and challenges being posed to the pluralist character of the nation on the basis of religious identity, included secularism as a basic feature in the Preamble to the Constitution through the 42nd Amendment.

“In a multi-religious and multicultural society, the students need an educational system that equips them to acknowledge and accept diversity in society. Multicultural education must reflect upon coexistence for mutual benefit and the nation’s benefit. It must be capable of integrating diverse needs without affecting the distinct identity which they own for a unified vision of the society and the State. It must focus on reduction of prejudices, bias and promotion of democratic values. This would create an atmosphere of mutual respect and intimacy among students,” the judgment said.

“A private body that discharges public functions must adhere to constitutional values in regard to the discharge of public functions. It cannot adopt any character contrary or repugnant to constitutional morality or value. Individual freedom available to a private body to promote his own belief or faith is not available to a private body when it discharges public function. It is bound by public morality conceived in the Constitution. Every public functionary is, therefore, bound to sustain the shared morality of a multicultural society,” the verdict said.

The Court was of the opinion that in this case there is a clear finding that the school was imparting religious instruction exclusively relating to the Islamic religion. “This cannot be permitted. Since it offends the very fabric of the secular society, the Government is justified in ordering closure of the school. However, taking note of the peculiar facts and circumstances of the case, this Court is of the view that an opportunity should be given to the petitioner to desist from imparting religious instructions or study without permission from the Government.”

The Court ordered that the state general education department ask all recognised private schools in the state to desist from imparting religious instruction or religious study without permission from the government. If in spite of the direction, schools continue to violate the order, the government can initiate action for closure and derecognition of such schools, the Court said.

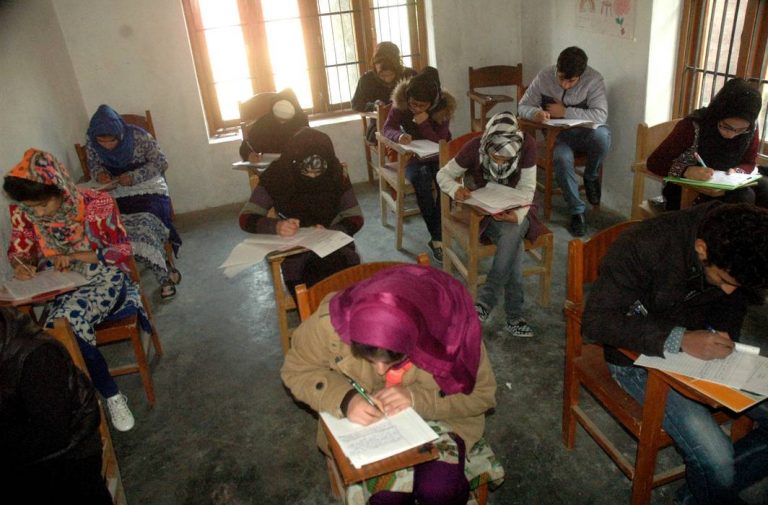

Lead pic: The HC considered the case against the backdrop of the Right to Education Act/Photo: UNI