By Sujit Bhar

The custodial death of 84-year-old Jesuit priest and tribal activist Stanislaus Lourduswamy, or Stan Swamy, is shocking, inasmuch as it was a result of pointed misapplication of a draconian law. Even the Bombay High Court lamented: “Despite our best efforts, Father Stan Swamy could not be saved.” Whither lie our fundamental rights, enshrined in the Constitution?

The idea of civil liberties in India is dead, rotting. It suffocated, yet survived the horrible onslaught of the Mughals, but was brutally stabbed and left to die during the Raj. Independence was supposed to resurrect the dead and hope staggered along, albeit with an ugly limp, before political apathy beat it down, again. As liberties were suspended during the Emergency, Amnesty International estimated 1,40,000 arrests, without trial, during those 20 cruel months. Those were the days of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA). Passed in 1971, it gave then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her dispensation broad powers, including indefinite preventive detention, search and seizure of property without warrants, even wiretapping. Poet and activist Varavara Rao was detained during the Emergency, under MISA, as were hundreds of other intellectuals.

As memories of the Emergency faded, in 2002, came the brutal and draconian The Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA), passed on March 26, 2002. This replaced the Prevention of Terrorism Ordinance (POTO) of 2001. It was supposed to be softer than the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) (1985-1995). It was anything but.

Even as POTA came into effect, there were already 200 people behind bars for “supporting Naxals”, including a 12-year-old boy, Gaya Singh and an 81-year-old Rajnath Mahto. Even before the Act was in force, the preceding ordinance had incarcerated 10 children.

Meanwhile, The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) of 1967 was growing past adolescence in government nurseries.

In January this year, the UAPA claimed its first victim, in adivasi Kanchan Nanaware, a 38-year-old students’ rights activist from the Chandrapur district of Maharashtra. She was arrested in 2014 for her alleged role in the Maoist movement, but in just over six years, she was dead, through a heart and brain ailment, at the state-run Sassoon hospital in Pune. She never reached trial. For two years, she petitioned the courts—both, the Sessions Court and the Bombay High Court—for bail. Her lawyer Parth Shah says: “Each time, it was rejected.” It didn’t matter that doctors had recommended a heart transplant for her. That bail application remains pending. The bigger horror was that neither the jail nor hospital authorities had informed the lawyer or her family of a brain surgery secretly conducted on her on January 16.

The second UAPA victim was Stan Swamy. This time, the Bombay High Court condoled the death of the activist and was also critical of the lower court’s lack of proper action. The bail application of Swamy, a Parkinson’s disease patient, was treated with complete contempt by the Special National Investigation Agency (NIA) Court on October 23, 2020. Even when Swamy asked for a sipper—a plain paper straw—because he could not even hold a glass of water, the NIA asked for 20 days to respond. When they did, the NIA said it did not have one—generally available at any fruit juice stall across all cities of India.

Swamy’s second bail application—saying that he was 83 and a Parkinson’s patient, plus with failing health—was adjourned without any proper reasons assigned. The only positive from this—that too after a public outcry—was that his appeal for a straw sipper and warm winter clothes was deemed non-threatening to national security. The Taloja Jail authorities could have, on their own, supplied these.

Also Read: ITBP candidate declared unfit for having tattoo on wrong arm, Delhi HC upholds order

Another bail application by Swamy in November 2020 was dismissed by the Special NIA court on March 22, 2021. The probe agency had already completed its investigation and wanted Swamy in judicial custody, not police custody. This means, that there was no further need for interrogation.

By then Swamy was critical. On May 28, 2021, the Bombay High Court directed the Maharashtra government to get Swamy admitted to a private hospital for 15 days and he was moved to the Holy Family Hospital in Bandra. Swamy had refused to be removed to a hospital, and wanted bail instead, or wanted to die in jail. But that was his pride, his ramrod straight character and his belief in his own innocence.

The system can lament, the system can apportion blame, but the system never interfered, never once tried to understand why a man would want to live among tribals and work for them, ignoring calls to comfort. Death was virtually delivered to Swamy’s cell by the system.

Return to Varavara Rao, 81, a celebrated activist, poet, teacher, and writer from Telangana. He is now an accused in the 2018 Bhima Koregaon violence case, also arrested under the UAPA. He is out on a six-month conditional bail, after his wife kept on petitioning courts, but Rao’s brilliant mind is already corrupted under constant and immense duress. By the time the courts agreed to move Rao, his mind was mush, his spirit was behind a thick mist of dementia and the need for physical or mental torture had been exhausted.

These are not isolated incidents. These are not restricted to one administrative group. It pervades all colours in the political spectrum, all manners of stated ideology.

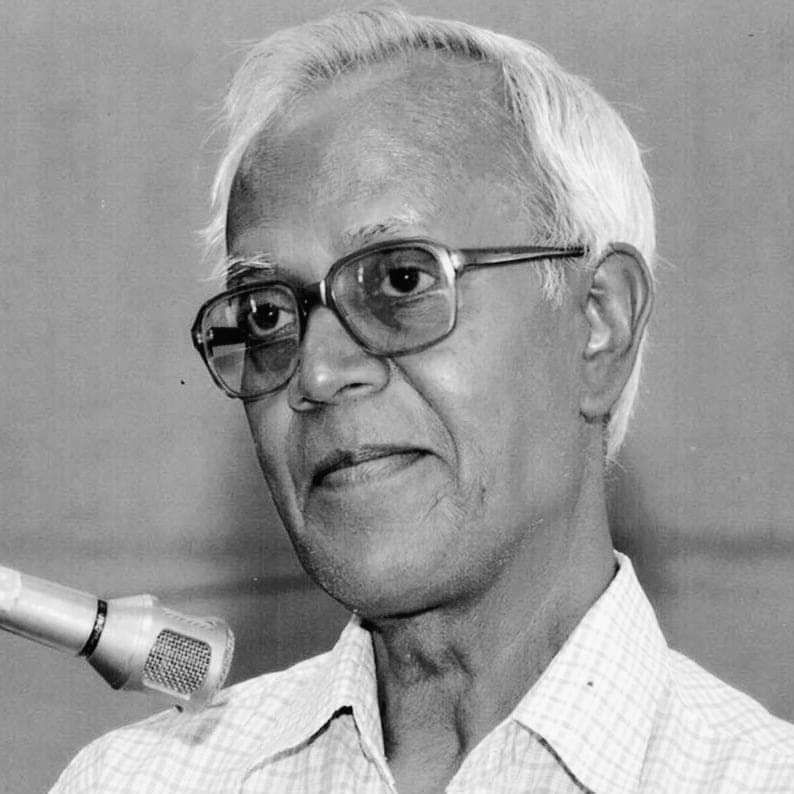

Think of Dr Binayak Sen. A paediatrician of repute and a public health specialist, he was also the national Vice-President of the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL). It didn’t matter that Sen was the recipient of multiple international awards, including the Jonathan Mann Award, the Gwangju Prize for Human Rights and the Gandhi International Peace Award. His flaw was his sympathy for the weak, the downtrodden, the tribals of Chhattisgarh. As Sen practised medicine among the tribal people, he came face to face with the immensity of government insensitivity. He protested, criticised the government on human rights violations during the anti-Naxalite operations through Salwa Judum. He advocated non-violent political engagement, but was picked up and convicted for sedition by a local court, later upheld by the High Court of Chhattisgarh, before being granted bail by the Supreme Court. He was convicted for life. What were the laws used against him? The Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act 2005 (CSPSA) and the UAPA.

Every manner of man protested the incarceration of Sen, who has been published even in the prestigious British medical journal The Lancet (February 2011). Noam Chomsky and several other prominent figures issued a press statement in June 2007, alleging that “Dr Sen’s arrest is clearly an attempt to intimidate PUCL and other democratic voices that have been speaking out against human rights violations in the state”. In May 2009, the Supreme Court released him on bail. The cases continue.

Even at this point of time, behind bars is Hany Babu, admitted at the Breach Candy hospital at his own expense after he tested positive for Covid-19. Also behind bars is Sudha Bharadwaj, Gautam Navlakha, Anand Teltumbde, Rona Wilson, Vernon Gonsalves and Arun Ferreira. Except for Sudha Bharadwaj, all the other accused remain lodged at the Taloja prison in Navi Mumbai.

It is not the alleged crime, but the right to bail that is being scotched by the system. By extension, this is the right to life. Nobody needs to die, just to prove that he/she is too ill to be behind bars, even as his/her crime remains to be proved.

This column is from this week’s India Legal magazine issue with the title ‘Patriot Acts’.