The Law Commission’s 273rd Report asks the government to put a stop to endemic torture

~By Venkatasubramanian

It does not require a compilation of a series of reports or judicial pronouncements to show that torture is dehumanising, and its perpetrators must be brought to book. The Law Commission’s 273rd Report does precisely that. The danger that it could be seen as an academic exercise may exist, but if it leads to a positive change in the mindset of our lawmakers, that will be reward enough.

That the inspiration for the Law Commission’s exercise comes from a pending case before the Supreme Court must speak volumes for the degree of judicial intervention in such issues, even if the degree is only perfunctory, and not worth celebration.

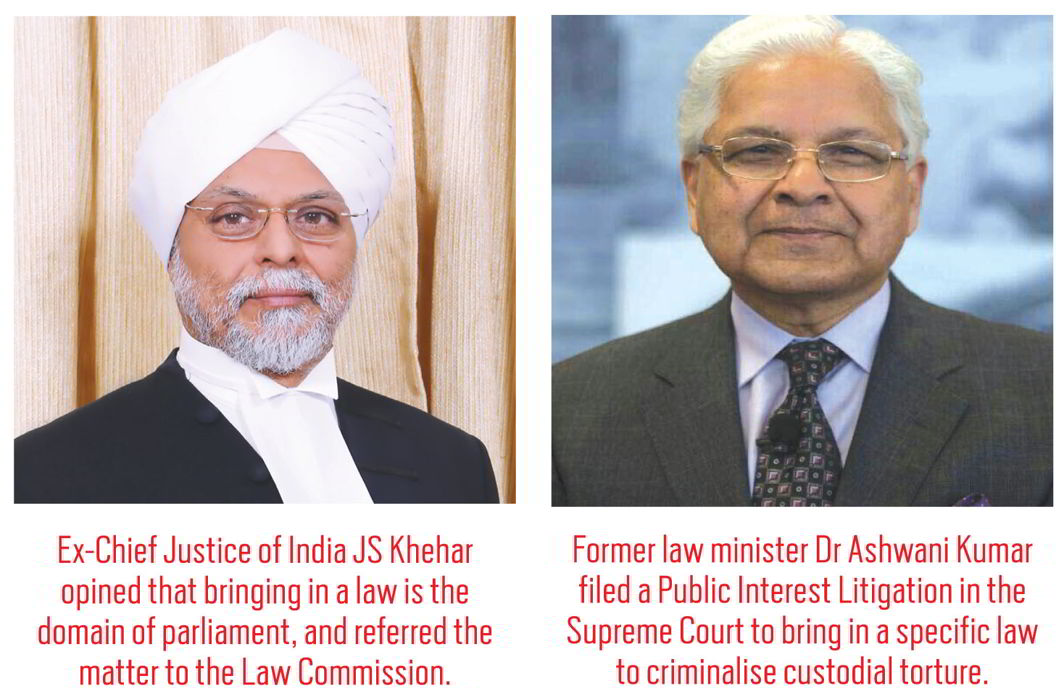

Former law minister Dr Ashwani Kumar filed a writ petition in the Supreme Court in 2016, seeking issue of directions to the centre and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) to ensure an effective and purposeful legislative framework and its enforcement to fulfil the constitutional promise of human dignity and prevention of custodial torture at all levels. The case, which has been listed for hearing eight times so far, is still nowhere near resolution, with the centre seeking adjournments, citing likely consideration of the issue by parliament. In May this year, the then CJI, JS Khehar, observed that the legislative determination is essentially within the domain of parliament, and as such it may not be proper for the court to issue any direction in that behalf.

The writ petition, which is likely to be listed before the Supreme Court on November 27, however, acted as a trigger, propelling the centre to write to the Law Commission in July, to examine the issue of ratification of the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and submit a report on the matter. On October 30, the Commission submitted its 273rd Report to the centre, recommending ratification of the UN Convention against Torture, enactment of stand-alone legislation and amendments to the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), 1973, and the Evidence Act, 1872.

Kumar was justly concerned about the issue, having been the chairperson of the Rajya Sabha select committee which examined the then government’s bill against torture, which was passed by the Lok Sabha without debate.

India signed the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (adopted by the General Assembly of the UN on December 10, 1984, known as the UN Convention Against Torture (CAT)) on October 14, 1997. But it has not yet ratified it, because of its reservations against certain provisions in the Convention, namely, Inquiry by the CAT (Article 20); State complaints (Article 21) and individual complaints (Article 22).

Despite such reservations, the centre introduced the Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010, in the Lok Sabha, to give effect to the provisions of the Convention. The bill was passed by the Lok Sabha on May 6, 2010. The Rajya Sabha referred the bill to a select committee, which had proposed amendments to the bill to make it more compliant with the CAT. However, the bill lapsed with the dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha.

Although the previous UPA government could not enact the bill, which it introduced during its term in office, it did not come in the way of its former law minister, Kumar, filing a writ petition in the Supreme Court, to goad the government into action. “India faces problems in extradition of criminals from foreign countries because of the absence of a law against torture, and it is in our own national interest to have such a law,” he said in his petition, and sought proper guidelines to prevent torture, cruelty, inhuman or degrading treatment towards jail inmates.

Not ratifying the CAT may lead to difficulties in cases involving extradition, as foreign courts may refuse extradition or may impose limitations in the absence of an anti-torture law in line with the Convention, while granting extradition.

Police use torture in order to achieve quick results by short-cut methods. Causing hurt is a punishable offence under Sections 330-331 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, but the atrocities, if committed within the four walls of the police stations, can leave no evidence, and as a result, the conviction for torture of police has been rare.

The Law Commission emphasised the courts have rejected the plea of sovereign immunity, which contradicts the essence of the law of torts. The law of torts provides that liability follows negligence and the individuals and the States are responsible for the negligence of their agents/employees acting in the course of their employment. While dealing with the plea of sovereign immunity, the courts will have to bear in mind it is the citizens who are entitled to fundamental rights, and not the agents of the State, the Commission’s report reads.

SALIENT ASPECTS

The wide definition of “torture” adopted by the Commission in its report would help to determine torture by a public servant. Thus, any act inflicting injury, either intentionally or involuntarily, or even an attempt to cause such an injury, which would include physical, mental or psychological injury, would be covered by the definition of torture.

In the Commission’s view, the CrPC and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 require amendments to accommodate provisions regarding compensation and burden of proof, respectively.

In the Commission’s view, the CrPC and the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 require amendments to accommodate provisions regarding compensation and burden of proof, respectively.

Thus, it recommended an amendment to Section 357B of the CrPC to incorporate payment of compensation, in addition to payment of fine as provided under Section 326A or Section 376D of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.

Similarly, the Commission reiterated its earlier recommendation, as carried in its previous reports, Nos. 113 and 152, that the Indian Evidence Act requires insertion of Section 114B. This will ensure that in case a person in police custody sustains injuries, it is presumed that those injuries have been inflicted by the police, and the burden of proof shall lie on the authority concerned to explain such injury.

But it is in the stringent punishment of the perpetrators of such acts that the Commission’s report makes a huge contribution. The Draft Bill annexed to the Report provides for punishment extending up to life imprisonment and fine, in case of deaths of victims, and up to 10 years rigorous imprisonment in other cases.

The Commission observed that the courts will decide upon justiciable compensation after taking into account various facets of a case, such as the nature, purpose, extent and manner of injury, including mental agony caused to the victim.

“The courts will bear in mind the socio-economic background of the victim and will ensure that the compensation so decided will suffice the victim to bear the expenses of medical treatment and rehabilitation,” the Commission hopes.

External Criticism

India’s steadfast refusal to ratify the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), despite having signed it in 1997, has come in for criticism from various international quarters. Individual countries such as the United States have also been repeatedly criticising India for the rampant use of torture by the police and security forces.

In 2012, at the second Universal Public Review (UPR) before the United Nations Human Rights Council, of the 80 countries participating in the Review, 22 States strongly urged India to immediately ratify the Convention and enact legislation to criminalise the use of torture by State agents.

At the third UPR, which was held in May this year, 36 countries raised the issue of torture during India’s review session, urging the government to ratify the UN Convention against Torture by enacting the Prevention of Torture Bill that has been pending before parliament since 2010. This came after the then Attorney General, Mukul Rohatgi, defended an army officer in Kashmir who had tied Farooq Dar, a civilian, to a military vehicle’s bonnet as a human shield. Rohatgi stated that the officer “did a smart thing and defused a nasty situation,” and that “the army should be applauded”. On May 22, 2017, Major Nitin Leetul Gogoi, the officer who took the decision to use the human shield, was awarded a Chief of Army Staff’s commendation card for “sustained efforts in counter-insurgency operations”.

The International Committee of Jurists (ICJ), in a 2012 report, and global human rights NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW), in a 2016 report titled “Bound by Brotherhood”, came down heavily on India’s practice of granting continued immunity to policemen and security forces personnel involved in custodial torture and custodial killings. The ICJ condemned the “epidemic of torture” in no uncertain terms.

In its India Human Rights Report 2016, the US State Department said that the most significant human rights problems plaguing India involved instances of police and security force abuses, including extrajudicial killings, torture and rape.

The report stated: “There continued to be reports of custodial death cases, in which prisoners or detainees were killed or died in police custody. Decisions by central and state authorities not to prosecute police or security officials despite reports of evidence in certain cases remained a problem.”

COMPARISON WITH 2010 BILL

The Law Commission’s draft bill needs to be compared with the previous bill, introduced by the UPA. This bill, introduced in 2010, was conceived merely as an enabling piece of legislation to ratify CAT, and lapsed the same year.

According to the UPA government’s bill, the word “torture” was defined as an act which must either cause grievous hurt or must cause mental or physical danger to life, limb or health. Article 1 of CAT, in contrast, defines “torture” as “severe pain or suffering whether physical or mental”. The word “severe” has been interpreted to mean “prolonged, coercive and abusive conduct which, in itself, is not severe, but becomes so over a period of time.”

Legal experts had then pointed out that repeated commission of certain acts may constitute torture even though the acts by themselves may not fulfil the criteria of the definition of torture. Thus it was felt that the term “grievous hurt” set the bar too high, with the result that severely hurt persons might not qualify as victims under the bill.

The Law Commission’s draft bill, therefore, defines an act of torture to mean causing grievous hurt or danger to life, limb or health, or severe or prolonged pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, or death. The bill, however, excludes mere mental agony or tension arising due to coercion from its definition of torture.

The Law Commission’s draft bill, therefore, defines an act of torture to mean causing grievous hurt or danger to life, limb or health, or severe or prolonged pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, or death. The bill, however, excludes mere mental agony or tension arising due to coercion from its definition of torture.

Moreover, the UPA Bill did not seek to punish a public servant who abets, consents, acquiesces to or conspires in an act of torture, but was aimed to punish only those who committed the act. The Law Commission’s draft bill fills this void, by including abetment or acquiescence of the public servant of or to the act of torture, within the definition.

In 2010, the Rajya Sabha select committee, while commenting on the UPA’s bill, had recommended enlargement of the definition of public servants to include those employed in government companies, or any institution or organisation, including educational institutions under the control of the Union and state governments.

The Law Commission’s draft bill, however, merely says a public servant would be any person acting in his official capacity under the central government or the state government.

As the UPA bill did not provide for any minimum punishment for torture, the select committee recommended a minimum punishment of three years imprisonment and a minimum fine of `1 lakh to be imposed on the person found guilty of torture. By not prescribing a minimum punishment of imprisonment, the Law Commission’s draft bill paves the way for lighter punishment, which would enable public servants found to have committed torture, to get away. This is an unfortunate dimension, which needs to be remedied before the bill sees the light of day.

The UPA bill was also criticised for laying down that an act of torture was punishable only when it was committed to extract a confession, and on the grounds of religion, race, and so on. Civil society activists had, however, suggested that an act of torture must be punishable irrespective of the reasons behind it.

The Law Commission’s draft bill requires the act of torture to have the purpose of extorting a confession or any information that may lead to the detection of an offence. The Law Commission appears to have missed the loophole here, because the public servant alleged to have committed torture might plead that these purposes were missing.

The bill had imposed a six months’ limitation on the lodging of complaints against torture. The select committee recommended increasing this period to two years, and vesting the courts with the discretion to relax it further to advance the ends of substantive justice. The Law Commission retains the six months’ limitation from the date on which the offence is alleged to have been committed, with a proviso that the court may condone the delay on sufficient grounds being shown.

The UPA bill suffered from another anomaly, that of shielding public servants charged with torture by requiring prior sanction for their prosecution. The select committee therefore suggested that if the required sanction was not granted within three months from the date of application by the prosecution, it should be deemed to have been granted. The Law Commission incorporates this recommendation in its draft bill.

The select committee also recommended a reasoned decision when sanction is declined, and making it appealable. The Law Commission’s draft bill includes both the recommendations.

Conclusion of the trial of offences under the bill within one year from the date of cognisance by the court, and inclusion of provisions to protect victims, complainants and witnesses were other recommendations of the select committee on the UPA’s bill, which have been incorporated in the Law Commission’s draft bill.

It remains to be seen whether the NDA government, led by Narendra Modi, displays the requisite political will to adopt the draft bill of the Law Commission, and invite public comments on it, so as to improve it further, and ensure its expeditious passage.