Above: Illustration by Anthony Lawrence

Crime against children has gone up over the years with one-third of the cases being sexual offences. Unless systemic flaws are removed, these heinous crimes will continue to make news

~By Chandrani Banerjee

In a shocking incident on December 2, two teachers of GD Birla Education Centre in Kolkata were arrested under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act for allegedly sexually assaulting a four-year-old student.

There are numerous such cases of children being sexually assaulted across the country.

Yet, the Union law ministry says that pending child sexual abuses cases number only 27,558 till July this year. This is just the tip of the iceberg, as National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) figures show that such spine-chilling cases are on the rise.

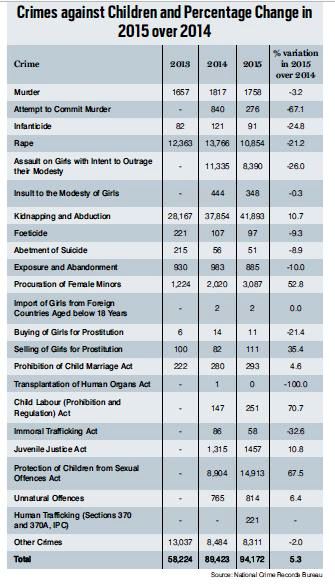

According to the NCRB’s latest figures for 2016, released by the home ministry on November 30, crimes against children have shown an increasing trend over the last three years. There was an increase of 13.6 percent in 2016 from 94,172 cases (in 2015) to 1,06,958. Kidnapping and abduction of children accounted for 52.3 percent of the cases, followed by cases under the POCSO Act at 34.4 percent, the number of which stood at 36,022.

The maximum number of cases of crime against children was reported from Uttar Pradesh with 4,954 cases, followed by Maharashtra at 4,815 cases and Madhya Pradesh at 4,717. In fact, the MP assembly recently passed a bill which allowed courts to award the death penalty to anyone found guilty of raping a girl aged 12 years or younger.

As for child sexual abuse cases, there are 12,990 of these pending in Maharashtra, followed by Kerala with 3,991 cases and then Rajasthan with 3,828 cases. While Uttar Pradesh has 890 pending cases, West Bengal has 283 and Uttarakhand is the last on the list with just four cases.

UNREPORTED CASES

Tara Narula, a pro bono lawyer who represents victims in child abuse cases, told India Legal: “The number of pending cases is certainly low compared to the actual rise in such cases. That’s because many cases go unreported. Child sexual abuse cases are different from regular rape cases. The duration of a case is vital in a matter where a child is a victim. If the crime is committed when the child is four years old and the case goes on for another two years, her thought process changes. It affects the case in a big way. The scenario here is such that even if someone is convicted in a lower court, he eventually gets an acquittal from a higher court.”

December 2, 2017: Two teachers of GD Birla Education Centre in south Kolkata arrested under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act for sexually assaulting a four-year-old student.

November 3, 2017: A one-year-old girl is raped by her 33-year-old neighbour in outer Delhi.

May 13, 2017: A 10-year-old girl was found pregnant after being repeatedly raped by her stepfather in Chandigarh.

May 12, 2017: A five-year-old deaf and dumb girl was raped by a 24-year-old man in Varanasi.

May 10, 2017: A 21-month-old baby was raped by a 40-year-old friend of her father’s in Delhi’s Gandhi Nagar area.

Seeing the growing sexual exploitation of children, the POCSO Act was introduced in 2012. Special courts were set up to deal with such cases. And the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) was asked to monitor and co-ordinate with the central and state governments as well as various ministries.

However, the recent spurt in child sexual abuse cases makes us wonder if the figures released by the home ministry are indeed correct. Child rights activist Sanjay Singh told India Legal: “These figures are very low. The reason is that sometimes the cases are registered under regular sections of the Indian Penal Code in small towns. In many cases, the accused is known to the victim, so due to family pressure, the cases are withdrawn after a couple of months. Most of the cases remain unreported. The social stigma is huge. For a mother to report that a father was sexually abusing her daughter would be an uphill task. And even if she reports it, she will often succumb to family and social pressures later.”

However, the recent spurt in child sexual abuse cases makes us wonder if the figures released by the home ministry are indeed correct. Child rights activist Sanjay Singh told India Legal: “These figures are very low. The reason is that sometimes the cases are registered under regular sections of the Indian Penal Code in small towns. In many cases, the accused is known to the victim, so due to family pressure, the cases are withdrawn after a couple of months. Most of the cases remain unreported. The social stigma is huge. For a mother to report that a father was sexually abusing her daughter would be an uphill task. And even if she reports it, she will often succumb to family and social pressures later.”

As senior advocate Kirti Singh, who has been instrumental in pushing for a change in laws pertaining to sexual harassment and assault, tells India Legal: “Apart from government agencies, there are many child rights activists who monitor and point out systemic flaws. But in small towns, this may not happen, so they remain unaccounted for and outside of the system. But more and more such crimes are happening and at a fast pace, and NCRB figures are proof of that. Reporting a case is not enough, it needs to be taken to its final stage.”

SPECIAL COURTS

The government, however, claims that every possible step is being taken to strengthen the special courts. There are special public prosecutors and special juvenile police units being set up. The law ministry works in tandem with NCPCR in such matters.

Speaking to India Legal, Stuti Kacker, chairperson, NCPCR, said: “To deal with sensitive cases of crimes against children, we have appointed 459 special public prosecutors, 727 special juvenile police units and 591 special or children courts in 694 districts. The effort is constant and we are trying to work towards creating a safe world for children.”

Narula said that there were other issues that were slowing down the process of accessing justice for such juvenile victims. “In November-end, the Delhi High Court noticed a pattern in acquittals by a POCSO court. All these stages are crucial when someone is fighting for justice.”

It may be recalled that in this case, the Delhi High Court noticed a string of acquittals by a POCSO judge in Saket district court, ASJ Sunil Choudhary, and decided to examine all verdicts delivered by him.

Justices Vipin Sanghi and PS Teji of the Delhi High Court, while hearing an appeal against one such acquittal, noticed a “fundamental error” in the verdicts. The bench said it would examine each judgment minutely.

It is obvious that the road to justice for child victims is long and tortuous.