The Supreme Court has upheld a Madras High Court judgment which denied permission to foreign lawyers to practice in the country but allowed them to visit for a temporary period to give advice to clients

~By Venkatasubramanian

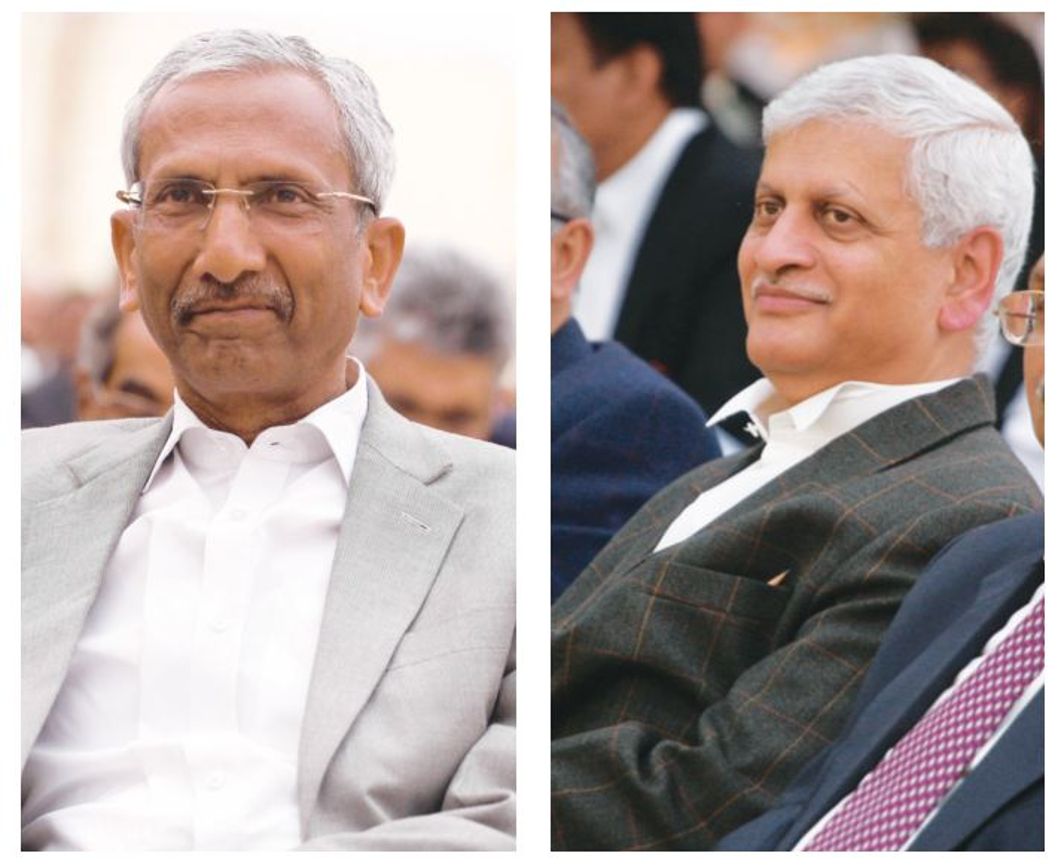

On March 13, a Supreme Court bench of Justices Adarsh Kumar Goel and Uday Umesh Lalit upheld the view that foreign law firms or foreign lawyers cannot practice the profession of law in India on either the litigation or non-litigation side. However, the bench made it clear that there is no bar on them visiting India for a temporary period on a “fly in and fly out” (FIFO) basis for the purpose of giving legal advice to their clients in India regarding foreign law or their own system of law and on diverse international legal issues.

The expression “fly in and fly out” the bench clarified, will only cover a casual visit not amounting to “practice”. The Bar Council of India (BCI) or the centre will be at liberty to make appropriate rules in this regard, including extending a code of ethics to be applicable to such cases, the bench held.

On the issue of conducting of arbitration proceedings by foreign lawyers in India, the bench held that they would be governed by a code of conduct applicable to the legal profession in India, and that the BCI or the centre could frame rules in this regard.

Modifying the direction of the Madras High Court, the bench held that BPO (Business Process Outsourcing) companies must be asked to lift the corporate veil. And if, in pith and substance, their services amount to practice of law, then the provisions of the Advocates Act (AA) will apply, and therefore foreign law firms or foreign lawyers will not be allowed to operate in the garb of such companies.

The main argument of foreign lawyers is that they are keen on non-litigious practice, which does not involve appearances before judicial fora in India, and therefore they should not be subjected to disciplinary control of regulatory bodies like the BCI.

STICK TO ETHICS

This the Supreme Court has rejected, saying that the ethics of the legal profession apply not only when an advocate appears before the court, but to regulate practice outside the court. “Adhering to such ethics is integral to the administration of justice. The professional standards laid down from time to time are required to be followed. Thus, we uphold the view that practice of law includes litigation as well as non-litigation,” the bench held.

The Supreme Court also rejected the other argument of foreign lawyers that the AA applies only if a person is practicing Indian law. The Court therefore found the view untenable that a foreign lawyer is entitled to practice foreign law in India without subjecting himself to the regulatory mechanism of BCI rules. The bench also did not find merit in the contention that the AA does not deal with companies or firms and only individuals. “If prohibition applies to an individual, it equally applies to a group of individuals or juridical persons,” it held.

In 2012, AK Balaji, the petitioner before the Madras High Court, had sought a direction to the central government, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Bar Council of Tamil Nadu to take appropriate action against 32 foreign law firms or foreign lawyers who, he alleged, were illegally practicing in India. Balaji argued that the procedure for Indian lawyers to practice in foreign countries is far more cumbersome and very costly, and there are also many restrictions like qualifying tests, prior experience, work permits and so on, but no such procedures are contemplated in the Advocates Act with respect to foreign lawyers who intend to practice in India.

ADVISORY ROLE

The AA provides that a foreigner may be admitted as an advocate if Indian nationals are permitted to practice law in his/her country. Balaji had also submitted that in the absence of enrolment in any of the state bar councils, in accordance with the provisions of the AA, the foreigners are not entitled to practice law in India on account of the bar contained in Section 29 of the AA. The Madras High Court, as a compromise between contending claims, had approved FIFO to facilitate foreign lawyers to come to India for a limited period to offer advice on foreign law to their Indian clients.

In a related case before Bombay High Court, Lawyers Collective had challenged the permission granted by RBI to some foreign law firms to open liaison offices in India. The High Court held that liaison activities were nothing but practicing the law in non-litigious matters. Both Bombay and Madras High Courts were clear that establishing liaison offices in India by foreign law firms could not be permitted since it was opposed to the AA and BCI Rules. The Supreme Court has disposed of appeals against both the High Court verdicts.

In its judgment on March 13, the Supreme Court has held that practice of law includes not only appearance in courts, but also giving of opinion, drafting of instruments, participation in conferences involving legal discussion. Chapter IV of AA makes it clear that advocates enrolled with the Bar Council alone are entitled to practice law, except as otherwise provided in any other law. All others can appear only with the permission of the court, authority or person before whom the proceedings are pending.

The centre initially took the stand that if foreign law firms are not allowed to take part in negotiations, settling of documents and arbitration in India, it would obstruct the aim of making India a hub of international arbitration. Many cases of arbitration with Indian judges as arbitrators and Indian lawyers are held outside India where foreign and Indian law firms advise their clients. Barring the entry of foreign law firms for arbitration in India would result in many cases of arbitration shifting to Singapore, Paris and London, contrary to the declared policy of the government and against national interest, it was pointed out by the centre.

However, the centre subsequently changed its stand, and favoured amendment of Section 29 of the AA, permitting foreign law firms to practice law in India in non-litigious matters on a reciprocal basis with foreign countries after consultations with the BCI. The centre then finally saw merit in the BCI’s stand that AA would apply with equal force to both litigious and non-litigious practice of law.

The BCI told the Supreme Court that the ethics it prescribes covers not only conduct in appearing before a court or authority but also in dealing with clients, including giving legal opinion, drafting or participating in law conferences. If a person practices before any court, authority or person illegally, he or she is liable for imprisonment which may extend to six months. The BCI, therefore, opposed Madras High Court’s endorsement of FIFO to give advice on foreign law or to conduct arbitration in international commercial cases of arbitration as erroneous.

BCI OPINION

The BCI also told the Court that Section 24 of AA lays down qualifications for admission on the roll of a State Bar Council. These qualifications include the citizenship of India, unless a person is a national of a country where citizens of India are permitted to practice.

The BCI had contended before the Supreme Court that the ethics for the profession as applicable in India are different from those applicable in other countries. The Supreme Court did not find it necessary to dwell on the ethical dimension of this debate, and confined itself to the legal and practical aspects of the controversy.

Much depends on the rules to be framed by the BCI or the centre to regulate the FIFO, and the role of foreign lawyers and their firms in arbitration in India. The Court has given the BCI the required discretion to determine whether in a particular case, a foreign firm or a lawyer has illegally practiced law in India. This is likely to open the doors for further litigation on this issue.