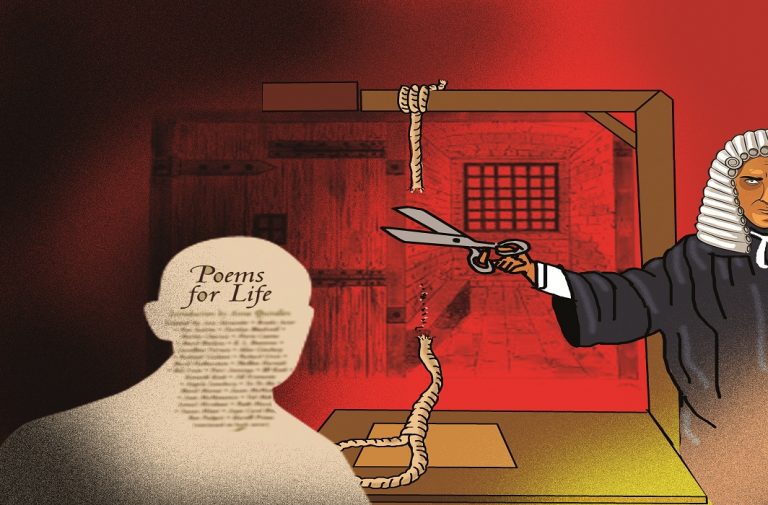

A convict had his death sentence commuted to life after the judges saw his poems and circumstances and felt it did not fit the “rarest of rare” category

By Prof NR Madhava Menon

Courts adopting therapeutic and reformative approaches in administering punishments are not alien to criminal courts in the country. However, in the matter of the death penalty, courts were more restrained and respected the mandate of the legislature. The best they could do was to limit its imposition to the “rarest of rare cases” and leave it to the judgment of individual judges to apply the standards to determine such cases on the lines set by the apex court. Despite many attempts to get the death penalty declared unconstitutional, the Supreme Court felt the need of retaining it in the statute book in the present circumstances. It was left to the Executive to recommend mercy by the president in appropriate cases. The discretion of the president in this regard has also been circumscribed through judicial review of the Executive privilege to give pardon.

The law thus evolved over a period of time got some twists and turns in the hands of “anti-death penalty” and reformist judges of the Supreme Court who found ways and means to commute death sentences to life imprisonment. Such an approach may appear alien to the sentencing jurisprudence obtaining in current times for “rarest of rare cases”.

One such instance was recently reported in a decision rendered by Justices AK Sikri, Abdul Nazeer and MR Shah of the Supreme Court. The media published the news with the headline, “Murder convict’s poem saves him from death sentence”, giving the impression that writing poems while in jail can save one from the gallows. The fact of the matter was that along with other facts and circumstances of the case, the poem with a reformative appeal persuaded the judges to decide that his case was not in the rarest of rare category.

The convict at the time of kidnapping and murdering a minor child was an adolescent. He spent 18 years in jail awaiting the gallows and all these years, conducted himself as a person who repented his crime. He endeavoured to be a civilised individual, continued his studies from jail and completed his graduation. He thus demonstrated to the Court that he was not a professional killer, was unlikely to repeat the crime if given a chance to integrate himself in society and was in no way a continuing threat to society. To add to these facts, his poem written in jail, though not with the hope of commutation of the death sentence, also strengthened the judicial inference of reformative potential. It is on the basis of this evidence that the court concluded that it was not a fit case for the death penalty under the “rarest of rare” principle.

The convict at the time of kidnapping and murdering a minor child was an adolescent. He spent 18 years in jail awaiting the gallows and all these years, conducted himself as a person who repented his crime. He endeavoured to be a civilised individual, continued his studies from jail and completed his graduation. He thus demonstrated to the Court that he was not a professional killer, was unlikely to repeat the crime if given a chance to integrate himself in society and was in no way a continuing threat to society. To add to these facts, his poem written in jail, though not with the hope of commutation of the death sentence, also strengthened the judicial inference of reformative potential. It is on the basis of this evidence that the court concluded that it was not a fit case for the death penalty under the “rarest of rare” principle.

What is the message the decision conveys in the matter of awarding the death sentence? Firstly, the “rarest of rare” principle remains the law of the land and must continue to guide the sentencing judge. Secondly, the purpose of retaining the death penalty in the statute book is not retribution in the conventional sense. It is intended to deter like-minded persons and prevent commission of heinous crimes even though its deterrent/preventive potential is a matter of doubt. Thirdly, reformation serves social goals in criminalising conduct and restorative justice to some extent gives relief to the victims as well. Expiation used to be sufficient punishment in ancient times. Coupled with remorse and compensation to the victim, restorative justice can reduce the gravity of the offence. In fact, this is the principle under which “plea bargaining” is introduced in the Criminal Procedure Code to let people regain their freedom from long incarceration.

One would have appreciated the judgment more if the Court had ascertained the views of the victim’s relatives before commuting the sentence of death. One of the weakest links of the present criminal justice system is its near total neglect of the victim. Alternatively, the Court could have heard the assessment of the case from experts who could have given the extent of reform on the part of the convict. Anyways, the judgment, if circulated among those awaiting death in jails across the country, will certainly help improve prison discipline and the conduct of convicts.

They will invent new ways of demonstrating their reform potential to strengthen their cases for being taken out of the rarest of rare category.

They will invent new ways of demonstrating their reform potential to strengthen their cases for being taken out of the rarest of rare category.

—The author is a former Director of the National Judicial Academy and is at present Hony. Director of the Kerala Bar Council MKN Academy for Continuing Legal Education, Kochi