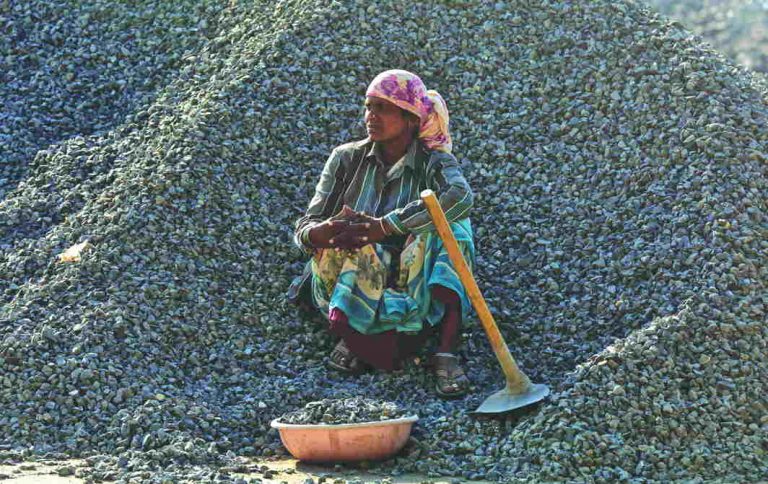

Above: Labourers working at construction sites often work for long hours in unhealthy conditions and get paltry sums of money. Photo: UNI

The lack of concern for these labourers is obvious: Despite the law allowing those freed to get a compensation of up to Rs 3 lakh, no one has received it as yet

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

It is a law that looks wholesome on paper. In two of its landmark judgments, People’s Union for Democratic Rights and others vs Union of India (1982), and Bandhua Mukti Morcha vs Union of India and others (1984), the apex court had said that anyone being made to work for less than the minimum wage is to be considered a bonded labourer. Under the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976, forced labour is prohibited.

Since May 2016, freed labourers are entitled to a sum of at least Rs 1 lakh from the government over and above an immediate assistance of Rs 20,000, which a few have received till date. If they are children/women or Dalits, this amount goes up to Rs 2 lakh and Rs 3 lakh, respectively. Additionally, they are to be given agricultural land, low-cost housing, minimum wage employment, free rations under the public distribution system and free education for children. All this is under the new and improved 2016 centrally sponsored scheme for the rehabilitation of bonded labourers.

However, the hard reality is that not a single freed labourer has availed the benefits of this new scheme even after more than a year of its existence. And though their numbers, especially those pertaining to agricultural debt bondage, have fallen over the years, bonded labour, also termed modern-day slavery, continues to thrive in India.

This is the blind spot of the government. Such is the neglect associated with the subject that there is no consolidated data on how many bonded labourers exist at any given time in India and the few estimates that are available, widely vary. The government can only provide figures of such labourers post release and rehabilitation, which are around 3 lakh and 2.85 lakh, respectively, since 1978. The first year, 18,889 such labourers were identified. That number has since fallen and was 2,607 last year.

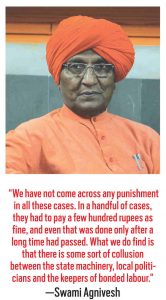

However, Prayas and Bandhua Mukti Morcha (BMM) of Swami Agnivesh, leading NGOs in this field, estimate that the total number of bonded labourers in India is 8.3 million and 20 million, respectively. The last nationwide government survey in this regard was done way back in 1993 and the figure that emerged was of 2.5 lakh.

However, the International Labour Organisation-Walk Free Foundation’s 2017 report says that there are 18.3 million bonded labourers in India, but their figure includes those forced into marriage and human trafficking. Bonded labourers in India work in stone quarries, brick kilns, mines, textiles, small-scale and cottage industries, homes and agriculture. Approximately 86 percent of them are Dalits.

However, the International Labour Organisation-Walk Free Foundation’s 2017 report says that there are 18.3 million bonded labourers in India, but their figure includes those forced into marriage and human trafficking. Bonded labourers in India work in stone quarries, brick kilns, mines, textiles, small-scale and cottage industries, homes and agriculture. Approximately 86 percent of them are Dalits.

Expectedly, loopholes in the law abound. The reason why the benefits of the new scheme have not percolated down to freed labourers is that it contains a clause according to which the consolidated assistance is payable only upon conviction of the employer. Swami Agnivesh, whose BMM has freed 1.78 lakh bonded labourers since 1978, said: “We have not come across any punishment in all these cases. In a handful of cases, they had to pay a few hundred rupees as fine, and even that was done only after a long time had passed. What we do find is that there is some sort of collusion between the state machinery, local politicians and the keepers of bonded labour. So, though the labourers are laid off because of pressure of the law, the employers, who should be charged, prosecuted and convicted, go unpunished.”

“Stringent punishment a must”

A change in mindset and greater engagement of civil society is necessary to eradicate bonded labour, former law minister Bandaru Dattatreya tells Sucheta Dasgupta. Excerpts:

How does your government plan to eradicate bonded labour?

Bonded labour is a harsh reality in India and has been going on for centuries. It is not possible to end it in a single day. We have laws to fight it, but the problem lies in implementation. For this, we require a mindset change and the involvement of civil society, people with new ways of thinking. Stringent punishment of those who carry on with the practice is a must.

Domestic workers still lack a legal definition in our country. They are not covered by the Minimum Wages Act in most states and also don’t have social security. What is your government’s plan to help them?

The centre is currently in the midst of preparing a detailed national policy for domestic workers which will address all these problems. Consultations with state governments are on and that is why it is taking so long to table it. But once they are over, a thoroughly designed policy will be brought out by the government.

By allowing children to work in family enterprises and cutting short the list of hazardous occupations for the employment of adolescents, the government seems to have legalised child labour. The 2016 Child Labour Amendment Act deprives children of the time to learn and play. What are your comments?

I do not think the Act in any way legalises child labour. If you read the Act carefully, you will see that it stipulates that the children may be engaged for only two hours of work, which leaves them enough time for homework and after-school activities. Also, the work they do will be considered as “help” in the family-run enterprise; there is no employer-employee relationship.

Under the 1976 Act, an enforcer of bonded labour is liable to be sentenced to a three-year jail term, and payment of a fine of Rs 2,000 or both. The same applies in the case of anyone who advances a bonded debt and extorts money from the labourer for a lifetime. This could be a money-lender, for instance.

Agnivesh, who was the force behind both the Supreme Court’s landmark judgments pertaining to bonded labour, is now fighting for the removal of this clause. In fact, the immediate assistance of Rs 20,000 was also not being disbursed earlier without conviction of the employer. It was Agnivesh’s talks with the National Human Rights Commission that resulted in the deletion of this criterion from the scheme, thus helping provide the crucial monetary boost to thousands of freed bonded labourers.

A little aid does go a long way. Birender, 30, and Tara Devi, 35, once worked together in the brick kilns of Bhadohi, Uttar Pradesh. While Birender had fallen into a debt trap in 2008 for a paltry loan of Rs 5,000, Tara Devi came from a family of bonded labourers. Both were paid Rs 150 as weekly wages, worked 18-hour shifts without leave and their movements were confined to their work and living areas. Such was their sorry plight that Birender lost his newborn niece at the kilns when she fell ill as the family was too poor to arrange medical treatment for her.

Tara Devi was rescued in 2010, Birender a year later. Both were freed by the efforts of Manav Sansadhan Evam Mahila Vikas Sansthan. Birender is now a mason with a small agricultural income. He has invested the compensation of Rs 20,000 he got from the government wisely by putting Rs 15,000 in a fixed deposit. Tara Devi is a seamstress and a candle-maker. Both were recently felicitated at a function by former labour minister Bandaru Dattatreya.

In the three years that he was labour minister, Dattatreya got some work done to improve the lot of people like Birender and Tara. It is he who initiated dialogue and revamped the rehabilitation scheme with the higher compensation amounts. This scheme was further amended in June-end and, more recently, a standard operating procedure (SOP) for the identification and rescue of these bonded labourers was decided upon. Thanks to the push by Agnivesh, the immediate assistance of Rs 20,000 to the bonded labourer is now to be given irrespective of the actual status of conviction proceedings of their employer.

It is the job of the DM, SDM or the police to file an FIR within 24 hours of the labourer’s release not only under the Bonded Labour System Act but also under the Minimum Wages Act and the Payment of Wages Act, whenever applicable. The summary trial must also commence during this time-span. The labourer must be provided protection during pendency of the trial.

Clearly, the success of the Act is heavily dependent on intent and implementation. Unfortunately, bad policing, bureaucratic red tape and administrative corruption stand in the way. Plus, the government is callous in identifying bonded labourers. It is required by law that at the district level, a vigilance committee should be formed headed by the district magistrate and comprising officials and activists. But often, it is found that the vigilance committee has not even been formed.

The NGOs themselves are strapped for resources. As Bhanuja Sharan Lal, MSEMVS executive director, told India Legal: “We are unable to reach everywhere. In many parts of the country where bonded labour is most prevalent, like the South, especially Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, we do not have a strong presence and have to solely depend on the government. Everyone cannot be helped.”

Thus, besides more legislation to close the loopholes, what is also required is the administrative will for implementation. Minimum wage, too, must be rationalised. Since Independence, it is being fixed by the state government. But the methods used to calculate the minimum wage are unscientific and the wage often too low, typically around Rs 5,000, to make a difference.

While it was Dattatreya who got the Wage Code Bill, 2017 (it consolidates four existing laws—the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, the Payment of Wages Act, 1936, the Payment of Bonus Act, 1965, and the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976) cleared by the cabinet and introduced in parliament in the last session, it has come in for criticism.

While it was Dattatreya who got the Wage Code Bill, 2017 (it consolidates four existing laws—the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, the Payment of Wages Act, 1936, the Payment of Bonus Act, 1965, and the Equal Remuneration Act, 1976) cleared by the cabinet and introduced in parliament in the last session, it has come in for criticism.

The government, for instance, has refused to stick to the Seventh Pay Commission recommendation of Rs 18,000 as the monthly minimum wage. Trade unions and activists fear that this will result in the wage being fixed so low that it will cease to be relevant. Their misgivings take on resonance especially in the light of the disturbing finding that even some of the minimum wages fixed arbitrarily by state governments are actually higher than what the central government has been paying under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA) scheme which also only guarantees 100 days of work annually.

“We need employment guarantee for at least 300 days a year and a national, rational minimum wage,” said Agnivesh. “Let the national minimum wage be fixed at a monthly Rs 26,000 equal to that of junior most employees. They have 30 years service guarantee as per the Seventh Pay Commission, and their work is far less arduous and hazardous than that of unorganised labourers whose average pay comes to only Rs 8,000.”

Citing the case of MNREGA, ASHA, anganwadi and midday meal workers, who are government employees but receive a monthly remuneration of even less than Rs 8,000, Agnivesh adds that the government should make the national minimum wage a movement and start implementing it with its own workers.

Where there is a will, there is surely a way.