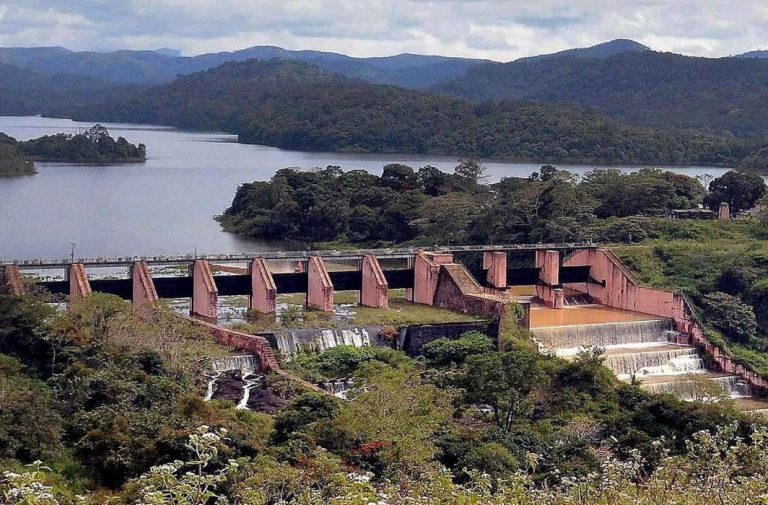

Above: The 100-year-old Mullaperiyar dam is located near the Tamil Nadu-Kerala border

In the wake of the devastating deluge, Kerala and Tamil Nadu once again take their fight over water levels in the dam to the Supreme Court

By Stephen David in Bengaluru

As a unit of measure, three feet is the height of a normal cricket bat. But that’s exactly the height over which flood-devastated Kerala and neighbouring Tamil Nadu are fighting each other—the bone of contention being what constitutes dam safety levels at the Mullaperiyar dam. Built in the upper reaches of Western Ghats in Kerala, it is operated by Tamil Nadu under a British-era lease. Kerala says 139 feet is one safety level. For Tamil Nadu, it is 142 feet.

For Kerala, three feet is not just a unit of measurement but the difference between life and death. Three feet could mean safety to three million people living downstream of the dam on the Periyar basin. For Tamil Nadu, increasing the water level by three feet to 142 feet means irrigating more land in the arid parts of the state.

With no stopping the flood of charges and counter-charges, the Supreme Court, which has been hearing the dispute, has now asked Tamil Nadu to reduce the water level to 139 feet till August 31, while posting the matter for further hearing to September 6 and asking other southern states including Puducherry and Karnataka to also file their responses.

On August 23, in a 10-page affidavit before the apex court, Kerala blamed the sudden release of water from the Mullaperiyar dam for the deadly deluge in God’s Own Country that killed over 300 and displaced nearly nine lakh people.

However, Tamil Nadu, seeking time to file its counter, denies that charge. “We are only concerned with the safety and lives of people,” Chief Justice Dipak Misra told the Tamil Nadu legal team even as the top court decided to take up the case again on September 6.

With the rains grinding to a halt and post-flood relief and rehabilitation measures taking centristage, Kerala is hoping that the apex court will come up with a new formula to ensure that there are proper mechanisms and regulatory bodies to cap the water level at the Mullaperiyar dam at lower levels—anywhere between 136 feet and 139 feet— preferably constantly monitored by a supervisory committee comprising the Central Water Commission chief and the secretaries of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Even a management committee from the centre to manage the daily operations at the dam will be helpful.

Kerala let go of an opportunity to stake claim to at least partial ownership to operate the 17-storey-high dam when the agreement was revisited in 1970 long before it took the 2006 legislation enactment route to force lowering the dam water levels to what it termed safe levels: 136 feet from the 152 full reservoir level that the dam is designed for. Tamil Nadu has kept the water levels at 142 feet for a long time after intervention from the judiciary.

The apex court will also ask for a detailed flood disaster management plan apart from submissions on future flood threats from the dam. The new info before it will help state governments and key central agencies to consolidate a pan-India foolproof disaster management plan to deal with calamities—natural or what prominent ecologists like Madhav Gadgil said about Kerala, “man-made disaster”.

Professor Gadgil’s 522-page report to the centre in 2012 had warned of the catastrophic threats from deforestation and illegal plundering of the Western Ghats, one of the world’s top biodiversity hotspots, to other parts of Kerala abutting the Ghats.

Gadgil had headed a 14-member panel which included five from top central government bodies including the national biodiversity board which, among other recommendations, called for establishing a separate policing force, Western Ghats Ecology Authority, which many say could have helped stave off the crisis that Kerala is crippled with today.

Many years ago eminent water expert Ramaswamy Iyer, a specialist in inter-state water disputes, had said that every dam has a shelf life: the dam in question was built in 1895 by a British army engineer and his team, braving nature’s fury.

Most dams, said Iyer, are meant to last a century and even with some engineering structural strengthening, it cannot be there forever. That’s one line of thought that Kerala hopes to leverage to hammer home the point of dam water level safety.

Way back in 1979, media reports on Mullaperiyar dam safety caught the attention of the centre. Later that year, the Central Water Commission held a meeting with top representatives from Kerala and Tamil Nadu and initiated some emergency measures for strengthening the dam. After additional engineering work on the dam, it was decided to raise the water level to 145 feet.

Kerala, hoping to get some relief, lost it again. The matter became sub-judice with several petitions until, on the apex court directive, a June 2000 expert committee was asked to study the safety of the dam. This committee’s March 2001 report added to Kerala’s woes: with some dam strengthening, it said, 142 feet is a safe water level. It threw in a kicker too: Tamil Nadu could raise it to 152 feet—another 10 feet—after additional strengthening measures.

In its February 2006 orders, the Supreme Court permitted Tamil Nadu to raise the dam water level to 142 feet and carry out the remaining strengthening measures. The following month, Kerala hit back by passing the Kerala Irrigation and Water Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2006 (on March 18, 2006) which prohibited the raising of the water level beyond 136 feet in the Mullaperiyar Dam and placed it in the Schedule of “Endangered Dams”.

Tamil Nadu filed a suit in the apex court on March 31, 2006, calling Kerala’s Act unconstitutional. The centre played referee by convening an inter-state meeting of the Kerala and Tamil Nadu chief ministers on November 29, 2006 but it was a dead ball. No consensus. Even with the then prime minister intervening in December 2007, it ended in a deadlock.

In April 2010, an empowered committee was set up headed by Justice Dr AS Anand. After holding more than 20 meetings including site visits, the Anand Committee in its April 2012 report to the apex court concluded that the “dam is hydrologically safe and that the proposal of the State of Kerala to build a new dam requires reconsideration by State of Kerala”.

The Anand-led empowered committee also suggested two options: Kerala could construct a new dam and the existing dam may not be dismantled, demolished or decommissioned till the new dam construction is completed and it becomes operational. The second alternative is to repair, strengthen and restore the existing dam.

Following this, a constitution bench of five judges of the Supreme Court heard the Mullaperiyar Dam Case in July-August 2013, and in its May 5, 2014 judgment declared the Kerala Irrigation and Water Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2006 unconstitutional and directed the Union government to set up a three-member Supervisory Committee on the safety of the Mullaperiyar Dam on restoration of the FRL (full reservoir level) to 142 feet.

The following month, a three-member Supervisory Committee on Mullaperiyar Dam was set up with its office at Kumily, Kerala. Central Water Commission Chief Engineer (Dam Safety Organisation) LAV Nathan (the two other members included Tamil Nadu PWD principal secretary and Kerala Water Resources Department additional chief secretary) headed this team.

It was tasked with inspecting the dam periodically and recommending all the necessary measures to keep the Mullaperiyar dam functioning at the highest levels of safety.

For the people of Kerala, the century-old dam is an emotional issue: it is owned and operated by Tamil Nadu although it is located in Kerala.

On August 16, the bench of the Supreme Court—Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justice DY Chandrachud—asked the National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC), Kerala and Tamil Nadu government teams to lower the water level at the Mullaperiyar dam by three feet: from 142 feet (maximum capacity) to 139 feet.

The Supreme Court has asked for a detailed disaster management plan to be filed by August 24. Additional Solicitor General PS Narasimha and Cabinet Secretary Pradeep Kumar Sinha—on behalf of the centre—are monitoring the developments closely; India’s top bureaucrat Sinha, who has video conferenced with the Kerala and Tamil Nadu chief secretaries, will also, with inputs from Delhi-based central agencies, draw up a state-of-the art structural risk mitigation manual.

Whether to lower the dam level or raise it will be a part of the findings for the court that is expected to address all the concerns raised in the August 16 petition, including the charge “that no concrete steps have been taken by any of the States or Central government till date to implement the (court) directions in true letter and spirit”.

Another key charge for the current state of disaster is the “unpreparedness of the state and the central government during this natural calamity as there is no plan which is announced or communicated to the public at large till date”.

Has Tamil Nadu risked the lives of thousands downstream of the Mullaperiyar dam? Could the unprecedented natural calamity in Kerala have been tackled more effectively? Are politicos indifferent to the untold suffering of the people? What kind of warning systems will be effective? What is the ideal disaster management plan to avoid such catastrophic situations again?

Maybe this time the Supreme Court will put to rest all these concerns.