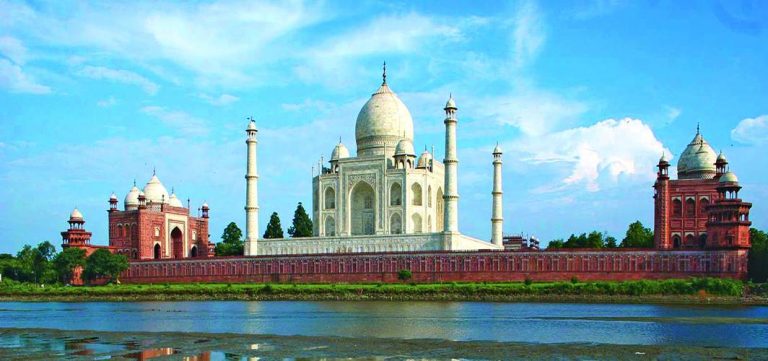

CIC has been asked to clarify if Taj is a mausoleum or a Hindu temple. Photo: wikipedia

In a bid to change the past, the RTI vehicle is being used to give the endeavour new respectability and thereby create a parody of a great legal institution

~By Shiv Visvanathan

Recently, I read a snippet of a report on how the Central Information Commission had been requested through an RTI to clarify by some historians whether Taj Mahal was a mausoleum built by Shah Jahan or a Hindu temple gifted to the Mughal emperor by a Hindu king. I was even more appalled by the normalcy with which the question was treated, as if it was “reasonable doubt” just waiting to be clarified.

My anger was two-fold. Firstly, the request was an insult to our sense of democracy and freedom of information. I felt the question was an insult to intelligence and to the activists who had struggled to enshrine the Right. Second, I felt it was an insult to my sense of history, my sense of the Taj Mahal as one of the wonders of the world.

I was complaining loudly about this to a psychologist friend of mine. He smiled and said impishly that is what makes Indians different. “They do not take dreams to bed, they are wedded to an idiot history. They feel that the only way that they can cure themselves is if they can cure themselves of their imagined history.” He confessed that it makes life interesting for a psychologist. “Looking at the BJP government through legalistic spectacle won’t do. They are trying to legalise their fixations. If law could alter history, they would be happy to use it.”

“Indians are a strange people who want the power and legality of history without the burden of history.” This statement was written by a friend of mine who found the current regime a curiosity. He asked me a set of intriguing questions. Firstly, why does India not have a tradition of science fiction? He answered that our lives and imagination are so full of aliens, gods, giants and monsters that science fiction seems unnecessary, a poor cousin of the colourful myths that we have. He then asked why is it that our attitude to history is so quaint. We have had alternative histories elsewhere but these are playful attempts to look at other possibilities and are used often as heuristics to understand the logic of choices. But our search for alternative histories is of a different kind. We want Akbar to be unseated, wish Rana Pratap had won the battle of Haldighati. We not only want to reverse history but want to include such reverse history in our textbooks.

A section of the Indian elite seemed ashamed of its recent past. It wants the middle periods of history to resonate with the past. We want our colonial and Mughal periods to be as glorious as our civilisational past. We find such history polluting and we want to erase it. My friend added wickedly that we are the only country that wants to sanskritise our history, make it more upwardly mobile than it is.

There are two reasons for this—as a majoritarian community, we seemed embarrassed with the docility and defeat of the past. When its history is embarrassing, the elite cannot hold its head high. Moreover, we want to be seen as a part of a global elite and we realise that we cannot do this without sanitising history. Our attempts to enter the rankings game also stem from a similar obsession. Being seen as part of the top dogs is essential for our political ego. An India that is second-rate and second class won’t do. India as a great civilisation but a third-rate nation state rankles. We want to be supermen leading superstates.

Our search for alternative histories is of a different kind. We want Akbar to be unseated and wish Rana Pratap had won the battle of Haldighati.

Secondly, we are not only embarrassed with our history, we cannot tolerate any group, especially a minority to have a greater history. Muslims can never be forgiven for building the Taj Mahal. To attribute the world’s most beautiful and legendary building with its sheer panoply of romantic stories to the other, would be an act of treason. If it was beautiful, it had to be Hindu. To concede that to the Mughal would be excessive. Such a historical envy needs a cure and the use of RTI to perform the ritual adds the right touch of perversity. To use a human rights vehicle to play around with history gives the endeavour a new respectability. Once the question is fired like an opening salvo, the bureaucratic mentality takes over. The Commissioners are asked to verify beyond “reasonable doubt” whether Taj Mahal was a gift from a Rajput Prince.

The motivation can be threefold. Harassment, paranoia or the sheer act of contempt, creating a travesty of history and the Right to Information Act. To verify such a speculation as a fact may be beyond the competence of the Commissioners. It also litters RTI with idiot problems creating a parody of a great legal institution.

The psychologist explained that often the trappings of enquiry, the ritual of a court proceeding gives an idiot question the gravitas of a scholarly enquiry. One does not need facts or certainty, even the possibility of what is respectably called an alternative narrative will do. All it reveals is the power of the regime to give respectability to such questions.

Yet dismissing them as ignorance or illiteracy will not do. One has to understand the persistence of the question, the empire of a fact built on the scaffolding of rumour. There could have been many Hindu craftsmen who built the Taj, there could be a mix of architectural styles. But to use this to create literally a speculative architecture might be far-fetched. The problem is that in a majoritarian regime nursing all forms of majoritarian resentment, such questions appear legitimate but they need to be treated as symptoms of a psychological syndrome. The psychologist added that during the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution, Russians made similar claims for priority, insisting that they had priority on a whole range of inventions. This epidemic of the pursuit of priority lasted for a while and faded out as Russia became more confident of its industrial and scientific might.

The Taj case is both a case of historical inferiority and political animosity. Such symptoms are deep-seated. They do not disappear when facts are contingent to the question. What one needs is a spectacle of controversy, a political Kangaroo court for a community to enact out its anger with history. Such a syndrome takes longer to disappear as charlatans and quacks as historians have a field day. As a wag referring to PN Oaks theory of the Taj Mahal said: “Only from such strange oaks do such mystifying acorns grow.” Humour and laughter might be a better response than any legal resolution.

—Shiv Visvanathan is a social science nomad