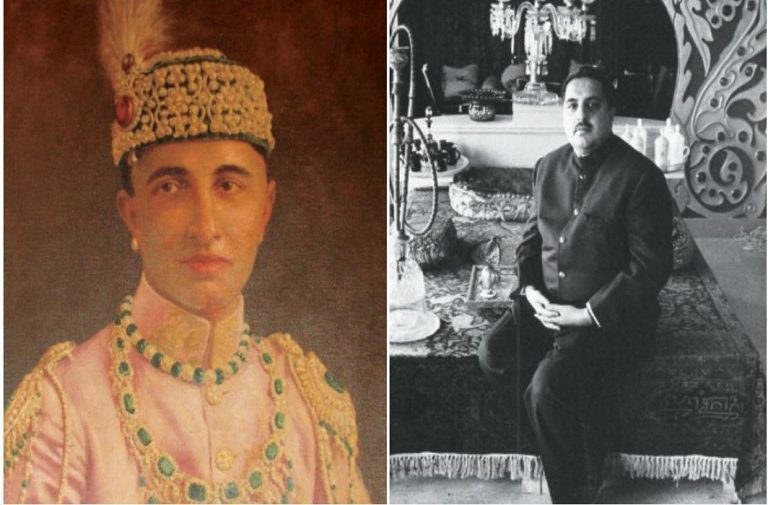

Above: (L-R) The last Nawab of Rampur, Nawab Raza Ali Khan, and his eldest son, Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur/Photo: geni.com

The apex court has brought to closure one of India’s longest running civil cases and given its consent to split the private properties of the ruler of Rampur state among all his heirs

By Govind Pant Raju in Lucknow

The Supreme Court has given a major decision on the succession of princely states which merged with the Indian Republic post-Independence. The judgment came as an answer to the predicament placed before the Court over the succession of private properties of Nawab Raza Ali Khan, ruler of Rampur.

Rampur, a princely state of British India, was merged with India on May 15, 1949. The state, which was birthed out of a treaty with Oudh in 1774, was merged with the Indian Union along with other nearby princely states such as Benares and Tehri-Garhwal. The state of Rampur was established by Nawab Faizullah Khan and remained a pliant state under British protection thereafter. Khan, a great patron of music and art, ruled for 20 years. The Nawabs of Rampur sided with the British during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and continued to play a role in the social, political and cultural life of northern India.

The case was one of India’s longest running civil suits, which the Supreme Court finally brought to a close after 47 years of trial and tribulation. It was appealed that the private property of a Nawab cannot be treated as the personal property of any other common citizen. Therefore, the property should be passed on to the “eldest male heir” while others should not get any stake in it. The bench rejected this argument and said that the decision has to be as per the Muslim Personal Law (Shariah) Application Act, 1937, as Nawab Raza Ali Khan was a Shia.

Khan, who acceded to the Indian Union in 1949, was, in turn, entitled to the full ownership of all private properties belonging to him on the date of the accession. The government also guaranteed succession to the “gaddi” or rulership of the state based on the customary law which conferred the property rights solely on the eldest son. Royal families that had acceded to India were also to receive a payment from the government known as the privy purse. Khan died in 1966, leaving behind three wives, three sons and six daughters.

As per the custom, his eldest son, Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur, succeeded as the head of the state. The government also recognised him as the sole inheritor of all his father’s private properties, issuing a certificate to this effect. However, his younger brother challenged this in a civil court and was later joined by three of his sisters. Thus began the great Indian royal property dispute in which the courts were to decide if the inheritance should be based on Muslim personal law or the customary “gaddi” system followed by the royal family.

In December 1969, the Delhi High Court quashed the certificate. This was challenged by Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur in the Supreme Court. The apex court chose not to intervene. Meanwhile, in 1970, using the Delhi High Court judgment, Talat Fatima Hasan, daughter of one of Raza Ali Khan’s daughters, moved a petition in a civil court in Rampur, requesting a division of the properties. This court then issued an interim order freezing all the assets.

The family squabble went into a further downward spiral: in December 1971, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi amended the Constitution and abolished privy purses. Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur lost out on his income, in addition to the estate being stuck in litigation. For the next 20 years, the suit remained pending before the civil court. In 1995, the Allahabad High Court withdrew the suit from the civil court and placed it before itself but Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur had died by then.

The Instrument of Accession made a distinction between Rampur state’s public properties, which had been acquired by the government of India, and the Nawab’s private properties, which were part of his inheritance. Lawyers representing Murtaza Ali Khan and his legal heirs argued that the private properties of the ruler were not entirely private—they were attached to the gaddi or the rulership. Therefore, their rightful ownership lay with the person nominated by the Nawab.

The apex court has now given its consent to split the private properties of the ruler of Rampur state among all his heirs. This means that now the women of the family are also entitled to a share in the inheritance. The Court stated that after the merger of the Indian Union, the rulers of princely states were Maharajas without sovereignty, and the state and other princely states had received the benefit of privy purses, personal property and privileges due to the provisions of the Constitution; otherwise they were equivalent to ordinary citizens. The Court said: “When they were actual sovereigns, their entire State was attached to the gaddi and not any particular property. There are no specific properties which can be attached to the gaddi. It has to be the entire ‘State’ or nothing. Since, we have held that they were rulers only as a matter of courtesy, to protect their erstwhile titles, the properties which were declared to be their personal properties had to be treated as their personal properties and could not be treated as properties attached to the gaddi.”

The Court has asked the trial court to appoint a commissioner for the division of the movable assets. It also said that the trial court may appoint a commissioner for disposal of the immovable properties. After the Supreme Court’s order, the property is likely to be divided into more than eight parts. However, many family members of the current generation have left Rampur. Mohammad Ali Khan, one of the members of Murtaza Ali Khan’s family, said in a media interview that if the decision of the apex court had gone in their favour, they could have done a lot with the property. But now that the decision has changed, the future seems uncertain.

Rampur estate is imbued with history and culture. The successors of Mirza Ghalib, Begum Akhtar and Tansen continued to get shelter in the state, resonating the claim of “Ganga Jamuni Tehzeeb”. There has always been an almost equal population of Hindus and Muslims here, but no riots have ever taken place. Murtaza Ali Khan Bahadur and Murad Ali Khan Bahadur were the last two heirs of this family, from whom the Nawabat was taken away in 1971. Now many palaces and buildings of this Nawabi clan are almost desolate or deserted. Some buildings such as Noor Mahal still have a few members of the royal family, including Murtaza’s brother, Marhum Zulfiqar Ali Khan alias Mikki Mian’s wife, Noor Bano, and her son, Kazim Ali Khan.

The fall of this once all-powerful dynasty is etched in Indian court procedures.