By Sujit Bhar

Recently, the BBC published on its website a quaint video, showing how the lamplighters of London—a 200-year-old job—are on the brink of being extinguished. Quite like its tottering monarchy, this is a tradition Londoners would like to hold on to but, well, can’t. Times have changed and five men, who still do this ludicrous Victorian era job in the 21st century—dating back to 1812—will be cast aside.

In India, we still hold on to manual scavenging—its justification possibly derived from Manusmriti, from as far back as the 2nd century BCE—and certain other inhuman jobs that should have been abolished with the first light of civilisation. Tradition is a good and a cruel thing. So is high tech.

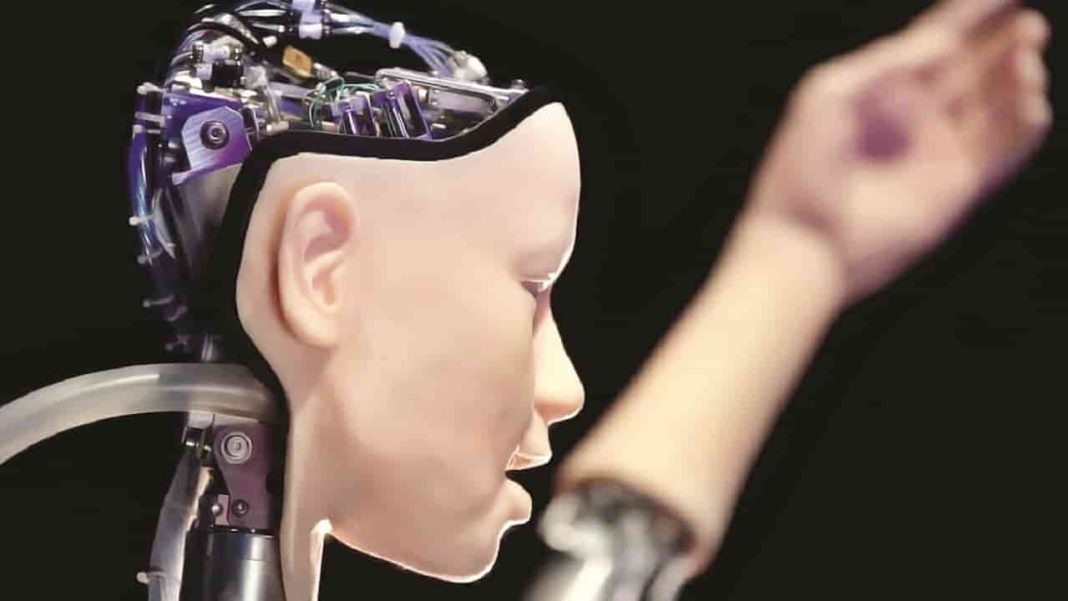

It is a little different with artificial intelligence (AI), though. AI’s prevalence in India will not be about holding on to tradition, but about providing jobs and basic sustenance to the poor, to those who simply cannot be upskilled above or near any level of AI competence. Every dispensation in power has neglected the spread of education in the country, till today “literacy” has become just the ability to sign your name. That will not cut in the new world.

Even before this decade started, it seemed there was hope. A World Economic Forum 2016 report had said: “…overall, our respondents seem to take a negative view regarding the upcoming employment impact of artificial intelligence, although not on a scale that would lead to widespread societal upheaval—at least up until the year 2020.”

While it predicted at that time the possibility of strong employment growth in engineering, architecture, mathematics, and computer jobs, with a moderate decline in production and manufacturing jobs, it also predicted significant decline in office and administration jobs.

Now, in 2023, let us put these predictions in perspective. AI has done little to change the slowdown pattern that India has been afflicted with, from the rest of the world, with all major economies in downturn.

That proves that while selective jobs may suffer, the overall system would trundle along as usual.

Let us look at agriculture, though. There is a problem brewing in the fields, if we look far enough. This is an extreme example, but a possible one, especially when India’s administrative lethargy is put in the backdrop. Trouble started with the mechanisation of agriculture, a character trait imported from the West, but necessitated within the greater objective of feeding a fast growing population. India’s green revolution was mainly due to mechanisation of large tracts of land and also due to the easy and economical availability of chemical fertilisers. These policies of the government have been very fruitful over the years.

ICAR assessment

Farm mechanization levels assessed by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) for major cereals, pulses, oil-seeds, millets and cash crops show that “seedbed preparation operation is highly mechanized (more than 70%) for major crops, whereas harvesting and threshing operation is the least mechanized (lower than 32%) for major crops except for rice and wheat crops. In seedbed preparation, mechanization level is higher in rice and wheat crops as compared to other crops. However, the mechanisation level for sowing operation is the highest for wheat crops (65%).”

These are interesting figures, but one must understand that these averages are availed of when large tract availability in the north of the country is taken into consideration. If one considers the low land holding situation in the east of the country, such as in West Bengal, when, in the name of land redistribution, tracts became so small that mechanisation became near impossible, then the situation changes. And the population density in these areas isn’t anything to ignore.

The other part of ICAR observations says: “The mechanization levels in planting/transplanting operation for sugarcane and rice crops are 20% and 30%, respectively. In the case of harvesting and threshing, the mechanization levels in rice and wheat crops are more than 60% and very less in cotton crop.”

It is always heavier on one side of crop growth cycle. This is more necessitated when you realise that farm labour is cheap and hiring farm equipment is not.

This is the backdrop against which we can consider the advent of AI in agriculture.

The India Initiative

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Artificial Intelligence for Agriculture Innovation (AI4AI) initiative wants India to integrate into the AI trend that is invading the fields across nations. The objective is to allow India to continue feeding its growing population “while also addressing such risks as climate change, pandemics and supply chain disruptions.”

What does this initiative entail? The WEF says that over 7,000 farmers are now using the technology “to monitor the health of their crops, perform quality control and test soil.” That sounds fair enough. However, like all tech, it will not stay put in one or a couple of regions. It will grow.

The forum says: “Led by the Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (C4IR) India and the Platform for Shaping the Future of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, the initiative brings together government, academia and business representatives to collaborate on the development and implementation of innovative solutions in the agriculture sector.”

There was a pilot project in place in Telangana through AI4AI. It was called the Saagu Baagu pilot, and was launched in partnership with the Government of Telangana, India’s first.

The focus of this pilot project is on chilli producers. At this point, these farmers get support “in the form of various AI technologies, including sowing quality testing, soil testing, crop health monitoring, window prediction and tillage estimation, as well as accessing new customers and suppliers in different geographies.”

Chilli produce—including relevant support in produce and associated value chains—was put under the lens because India produces nearly 36% of chilli worldwide, and nearly 23.5% of all chilli production in the country comes from Telangana.

All these developments are fine and should be supported by all. One should also support the use of drones within the system of agriculture, to sow seeds and to oversee large tracts of land. AI will help in these a long way. AI will also help in predicting climate trends and to optimise the use of water in irrigation. To such an extent, AI will be extremely useful.

But what happens when AI’s influence goes beyond the intelligence input? What happens when automated cropping and harvesting techniques accept AI inputs to become more independent? And this is bound to happen over time. Will this result in millions of poor farmers losing their jobs and livelihoods? Will this result in targeted cash cropping trends; will this result in furthering the poverty among the very poor?

These are issues that have to be kept in mind while dealing with AI-related tech in the Indian agriculture sector. We cannot afford to lose out on labour opportunities in this slowing economy. After all, nearly 58% of Indians depend on this for their livelihood. It is good that tech is used in growing more, but in the process we should not lose out on helping the poor benefitting from such developments.

Old jobs, like the London lamplighters will be phased out; but think of a situation where these lamplighters need to be upskilled to a point where they can deal with AI and related tech? A similar situation will arise with displaced Indian farmers. We need to be careful.