~By Inderjit Badhwar

That the invocation of Karnataka Pride should have become a focal point during the surcharged election campaign should hardly come as a surprise to anybody familiar with the development of linguistic states in independent India, and the constitutional tug-of-war between ideologies which seek a strong centre with the states as mere irritants, and those favouring stronger state rights and autonomy.

Actually linguistic tensions, starting in the 1930s when the idea of a new Indian nation was taking shape under Congress guidance, have been marked by bloodshed, mass agitations, self-immolation, student protests, police bullets, repression, anti-Hindi mass protests until the centre bent and compromised. These mass struggles, many of which matched the fury of the national independence movement against the British, ultimately led to the creation of Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Gujarati, Odia-speaking regional identities.

You just cannot wish away sub-cultural national pride in a diverse land like India. And the flagship of this social phenomenon is language. It bonds. It unifies. It soothes. It comforts. There is a Tamil saying that even if you hurl abuse at the gods in Tamil, they will forgive you. I am sure the people of Kannada have a similar sentiment. So it is no surprise that, taking a leaf from their Tamil brethren next door, the Karnataka Congress under Siddaramaiah wants to unfurl its own state flag. It is a matter for the record that when Hindi was sought to be imposed on the South, Dravidian parties actually threatened to launch an independence movement in 1968 after flying their own flag in Coimbatore.

The government at the centre was in a schizophrenic constitutional quandary. On the one hand, it espoused liberal federal principles (“cooperative federalism”) based on the instruments of accession of independent states under which India became a union. And yet, India’s liberal leader, Nehru, who swore by the doctrines of the Fabians and Utilitarians, scorned “linguisticism” which, he believed, could tear asunder the newly formed and still fragile nation.

Yet, wisdom seemed to have gotten the better of oppression and repression, as successive Congress governments realised that Hindi Raj—the linguistic and cultural domination of the rest of the country—by the heartland would only exacerbate rather than curb fissiparous tendencies. In fact, by the time Rajiv Gandhi came to power, intra-national treaties—pacts and accords—with rebellious regional leaders had become the order of the day: Compacts with Kashmir leaders, with the Nagas, with “Gorkhaland” agitationists, to name a few.

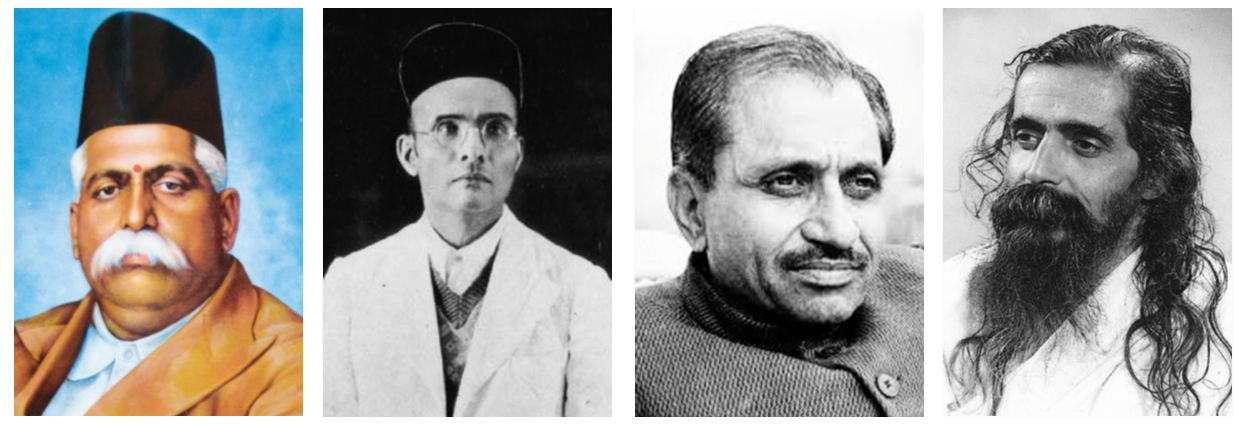

The Sangh Parivar has remained mostly opposed to the idea of diluting central authority. Hindi Raj, as expressed by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, VD Savarkar, Deendayal Upadhyaya and MS Golwalkar, is the only supreme national credo to create a unified resurgent Aryavart. Regional and anti-Hindi aspirations are, logically, anti-national.

But the tide of history, as the Congress realised, is not easy to stem, even with brute force. Narendra Modi recognises this when he dons cattle headgear while campaigning for votes in the beef-eating North-east or speaks of Gujarati “asmita” (pride) in his own home state or of Karnataka pride in Karnataka in order to out-flag Siddaramaiah’s chauvinistic appeal. Here is a man clearly pandering to aspirations which are ideologically anathema to the RSS ideology of Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan.

But wherever convenient, in order to make sure that he remains secure with his base, Modi will back with all the fervour at his command his Hindutva hawks’ condemnation of regional aspirations or autonomy for Kashmir as anti-national, subversive and seditious. This is not very different from how the Congress under Nehru viewed regional-linguistic movements or even Sheikh Abdullah’s mass movement for autonomy, now referred to as “azaadi”.

The architect of the Constitution, Baba Ambedkar, saw far into the future and actually built huge flexibility into the Constitution which would allow the centre to deal in various ways with states according to their particular circumstances, geography and ethnicity. Most people don’t realise that the “special status” for Kashmir isn’t really all that special. Article 370 is part of the Indian Constitution—it is the window through which Indian laws apply to Kashmir; the umbilical cord that binds the state to the Union.

On the one hand, the government espoused liberal federal principles. And yet, India’s liberal leader, Nehru, who swore by the doctrines of the Fabians and Utilitarians, scorned “linguisticism” which, he believed, could tear asunder the newly formed and fragile nation.

It is also not “special” because it derives from the huge latitude given to the centre for admitting new states (after independence was won) into the Indian Union. Article 2 of the Constitution states unambiguously: Parliament may by law admit into the union, or establish, new states on such terms and conditions as it sees fit [my italics]. Further, under Article 3: Parliament may by law a) form a new state by separation of territory from any state or by uniting two or more states or parts of states; b) increase the area of any state; c) diminish the area of any state; d) alter the boundaries of any state; e) alter the name of any state.

Even if you do choose to call the centre’s relationship with Kashmir “special”, it is not really that unique either. Under powers conferred to Parliament under Articles 2 and 3, the National Development Council (NDC) has accorded 11 states, out of 28, the status of “Special Category States” (SCS) to target the funds flow for better balanced growth. They are the seven states of the North-Eastern region (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura), Sikkim, Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. Other states are referred to as General Category States (GCS).

The SCS are highly dependent on grants from the Union government for meeting their financial requirements. These states show a revenue surplus position because any expenditure that they make on creating assets out of grants from the centre is not treated as revenue expenditure. This is contrary to the existing accounting standards which treat all expenditure from grants as revenue expenditure.

Manipur, Nagaland, Sikkim and Uttarakhand have a fiscal deficit which is higher than 3 percent (but less than 6 percent) of their GSDP and the 13th Finance Commission had indicated that they have to make efforts to reduce the fiscal deficit to 3 per cent by 2013-14. Jammu and Kashmir and Mizoram have higher fiscal deficits and require concerted efforts at reducing their debt stock to achieve targets set by the 13th Finance Commission. The other states—Arunachal, Meghalaya, Assam, Tripura and Himachal—have a fiscal deficit which is less than 3 percent of GSDP and therefore need to maintain their position to achieve the targets set out by the 13th Finance Commission.

Although the 12th Finance Commission recommended that all states (including Special Category States) should be permitted to borrow from the open market at market rates, the special dispensation given to Special Category States continues for external loans. In the case of the externally aided projects to SCS, the Union government treats 90 percent of the amount borrowed as a grant and only the remaining 10 percent is a loan. [Source of last three paras: Indian Economic Service.]

Further, Article 371 contains special provisions for Maharashtra and Gujarat establishing special development boards and priorities for technical education and training. Article 371-A, concerning Nagaland (in language similar to that pertaining to Kashmir), provides that no act of Parliament shall apply to religious or social practices of the Nagas, Naga customary law and procedure, administration of civil and criminal justice involving decisions according to Naga customary law and ownership or transfer of land and its resources “unless the legislative assembly of Nagaland by a resolution so decides”.

This is by no means a comprehensive list which includes Goa and the erstwhile Andhra Pradesh. But it indubitably indicates that aspects of autonomy and federalism are neither alien to nor enemies of the Indian State or Constitution. And regional satraps like Siddaramaiah and the TDP’s N Chandrababu Naidu are not out of line in asserting regional pride and demanding special provisions for their states.

As the BJP appears to be on an over-centralisation drive, the counter forces will only accelerate political moves to decentralise. The demands from the southern states are already becoming an undergirding political principle of opposition unity. Even more interesting, West Bengal’s Mamata Banerjee is spearheading an incipient movement for a “Federal Front” to combat and contain what she sees as the BJP’s ideology of a homogenous, unitarian, and majoritarian India. Bihar is joining the demand for special status and so is Odisha. Ironically, politically in this regard, Kashmir can no longer be singled out as the bad boy of the “appease us” brigade.

West Bengal’s Mamata Banerjee is spearheading an incipient movement for a “Federal Front” to combat and contain what she sees as the BJP’s ideology of a homogenous, unitarian and majoritarian India. Bihar is joining the demand for special status and so is Odisha.

Even though BJP leaders may play the “asmita” card when it suits them locally, at a national level, the trend is worrisome for them. While the Congress has produced regional leaders of gigantic, iconic standing and following—K Kamraj, C Rajagopalachari, Sucheta Kriplani, ND Tiwari, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Margaret Alva, KM Munshi, Morarji Desai, GK Moopanar, Vayalar Ravi, K Karunakaran, Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad, BC Roy, Jagannath Pahadia, Madhavsinh Solanki, YS Rajasekhara Reddy, Biju Patnaik, Dr YS Parmar, Mufti Mohammed Sayeed, Motilal Vora, YB Chavan, Pratap Singh Kairon, Bansi Lal—sons and daughters of the soil capable of handling and guiding regional aspirations, the BJP’s appeal, except for anti-Congressism and ideological religious polarisation, has been its heartland mobilisation.

The upshot of current trends was summed up by Garga Chatterjee in what is perhaps the most original and prescient piece I have read on the subject. He wrote:

“The distance between West Bengal and the Dravidian states is more psychological than geographical. In the Dravidian narrative, the ‘north’ is larger than north itself. The east too becomes ‘north’ in a narrative where north and south make up the whole domain. But no narrative fully covers reality. The east exists, often in a similar ideological stance against the north. The south doesn’t exist in that narrative. But if one looks at the map of non-BJP states in the Indian Union, it is the south and the east that form a continuous belt that prevents the spilling over of the [Sangh Parivar] Hindi-Hindu-Hindustan ideology into the holy waters of the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean.

“This continuity is not incidental. This is the zone of the politics of federalism. This is the zone whose absence would have created a Hindu rashtra called Hindustan with Hindi as its national language in 1947. This is the zone whose presence created the flawed but still nominally federal democratic entity called the Indian Union as it exists. It is in this context that the proposed Federal Front discussions in Kolkata on March 19 between Trinamool supremo and West Bengal chief Mamata Banerjee and Telangana chief minister and TRS supremo K Chandrasekhar Rao assume immense significance. A leader from the south is talking to a leader from the east without any Delhi party’s mediation on forming a political front based on the principles of federalism: a federal front. Whatever be the future of this proposal, this already is a sign of changing times.”

And all within the ambit of the flexibility of the Indian Constitution and established precedents.