The UIDAI-promoted Aadhaar is getting more complicated by the day. The on-going hearing in the Supreme Court is focused on potential security breaches. Adding to this is a project called Aadhaar Bridge, promoted by US-based entrepreneur Vinod Khosla. What does it do?

~By Sujit Bhar

On February 22, the Supreme Court constitution bench of Chief Justice Dipak Misra and Justices AK Sikri, AM Khanwilkar, DY Chandrachud and Ashok Bhushan was hearing submissions on several petitions related to Aadhaar linkages and their constitutional validity. Presenting his point of view, senior counsel Gopal Subramanium was pointing out the huge risks involved. He said that The Aadhaar (Targeted Delivery of Financial and Other Subsidies, Benefits and Services) Act, 2016, uses “national security as an umbrella. It is an act for identification, but it doesn’t recognise eligible recipients”.

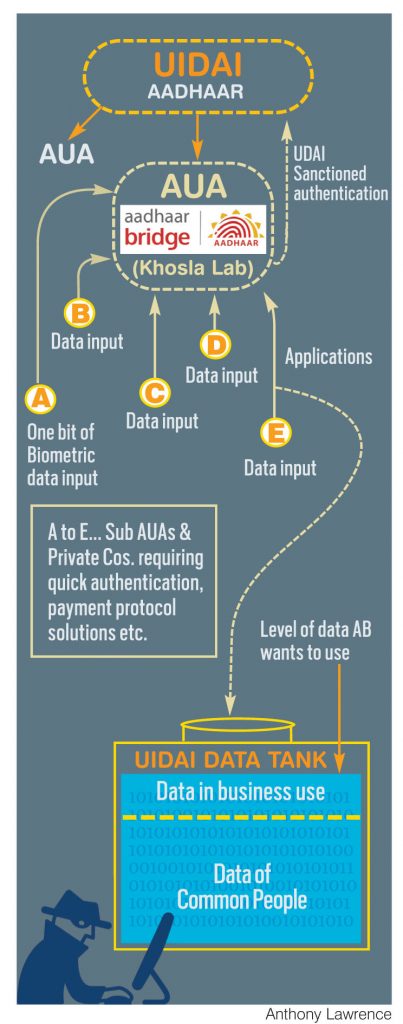

He presented before the court a worrying picture. One Authentication User Agency (AUA), formally registered with the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) and called Khosla Labs, has a ‘product’ called Aadhaar Bridge. The company, through this “Bridge”, is offering what it calls “an online service that makes it easy for companies to access the Aadhaar National ID system”.

What is worrisome in this? As Subramanium pointed out: “Today if you want to see anybody’s profile you can see it through state resident data. Through the Aadhaar Bridge anybody can go across and utilise the data stored in the process of Aadhaar. Earlier there was just an Aadhaar, now there’s an Aadhaar Bridge. It is highly shocking.”

He also said: “Private players are claiming to get you through the data, calling themselves ‘Aadhaar Bridge’. More so, because they are providing authentication process, providing facility of e-wallets, etc. I’ll show the credible documents from the government agency.” He also said that the Act has come into the picture to facilitate private parties. Justice Chandrachud asked at that point: “Does the Act authorise accessing of data? If it doesn’t, then how does Aadhaar Bridge get access to such data?”

That takes one to the complicated scenario that Aadhaar Bridge is. Aadhaar Bridge is a ‘product’ of the private company, Khosla Labs, promoted in India by an icon of the internet, US-based Vinod Khosla. Billionaire Khosla was a co-founder of Sun Microsystems. In India, the “Lab” is headed by Srikanth Nadhamuni, who was also the founding head-of-technology of the Aadhaar project.

Why is this private authentication issue so disconcerting? For one, the UIDAI-promoted and government-supported Aadhaar is getting more and more complicated by the day. It is spreading itself out so thin that it is opening itself up to constant security breaches that undermine its “national security” position, say experts.

According to cyberlaw specialist advocate Pavan Duggal, this is like a “house of cards” and the entire burgeoning ecosystem of Aadhaar has grown with absolutely no legal framework and, hence, no legal oversight. “We are playing with fire here,” he told India Legal (see box for interview).

There are three sides to this. First, if sensitive data is continually being dumped in the open—as has been found on several occasions, including a recent French online hacker’s claim that he took minutes to lay bare huge chunks of data, which he is threatening to dump—what security level will seal leaks and how will Aadhaar and its linkages be of benefit to common users? Second, if such data is allowed to be accessed in any form (however little of it) by a private entity, does that not impinge on a person’s or an organisation’s privacy? How can such sensitive data be packaged and sold by private parties without consent? That was a key question that Justice Chandrachud asked. And third is the complete absence of legal oversight, or even a legal framework.

What “services” does Khosla Labs provide? The platter is large, starting from legal, to auditing activities to management consultancy (see box). And what is its key activity? In defining that, the company refers to the Aadhaar Payment Bridge System (APBS), which is a “…payment gateway platform created by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI). It is used for Aadhaar schemes. It was used for the first time on 1 January 2013 when Direct Benefit Transfer was launched by Government of India.”

What is the width of the NPCI canvas? As per the website, “social security pensions, payments under the employment guarantee scheme, public distribution system, and stipend to the children returned to schools from work, Janani Suraksha Yojana, and scholarships will be covered under the Aadhaar Enabled Payment System…” and more. These are government services and not really what Aadhaar Bridge itself offers.

What this company offers is an access point for “companies to access the Aadhaar National ID system—hosted by the UID Authority of India (UIDAI)… Aadhaar Bridge offers services through online APIs for conducting Authentication and eSign transactions”.

And when much of the debate in the Supreme Court has been woven around the authentication process, this company provides it (quite like many other such registered authentication services or companies in the private sector). How? The simple explanation by this company is that “Aadhaar Authentication… is similar to user id and password being used while logging into say gmail. It is a person’s way of proving who she or he is. The Aadhaar Authentication API only returns a YES/NO response for a verification request.”

Herein lies the problem. When information is entered for verification, there is an “input” point. Some data is entered anyway, says Duggal. Even if the response from the UIDAI database is a simple Yes or a No, the original input is substantial.

The company’s website also refers to alternatives in authentication. It says: “Aadhaar Auths (authentications) come in 3 flavours:

A look into Khosla Labs

The following are details of Khosla Labs Pvt Ltd, as of December 25, 2017

It is a private (non-government) company, incorporated on October 5, 2012. It is registered with the Registrar of Companies, Bengaluru. Its authorised share capital is Rs 1 lakh and its paid-up capital is also Rs 1 lakh. The company is said to be involved in legal, accounting, book-keeping and auditing activities; tax consultancy; market research and public opinion polling; business and management consultancy. The directors at Khosla Labs, situated in Bengaluru East, are Nadhamuni (pictured above), Saraswati Janardana Tumuluri and Subir Mansukhani. Being an unlisted company, its shareholding details are not available.

It is a private (non-government) company, incorporated on October 5, 2012. It is registered with the Registrar of Companies, Bengaluru. Its authorised share capital is Rs 1 lakh and its paid-up capital is also Rs 1 lakh. The company is said to be involved in legal, accounting, book-keeping and auditing activities; tax consultancy; market research and public opinion polling; business and management consultancy. The directors at Khosla Labs, situated in Bengaluru East, are Nadhamuni (pictured above), Saraswati Janardana Tumuluri and Subir Mansukhani. Being an unlisted company, its shareholding details are not available.

Biometric Authentication: Uses the resident’s fingerprint or iris along with the Aadhaar number to verify the person’s identity.

Biometric Authentication: Uses the resident’s fingerprint or iris along with the Aadhaar number to verify the person’s identity.

Demographic Authentication: Uses the resident’s Aadhaar number and demographic details, such as name, address, gender or date of birth to verify the person’s identity.

OTP Authentication: Uses the resident’s Aadhaar number and a One Time Password (OTP) sent to the resident’s registered mobile number to verify the person’s identity.”

These are solutions that have been offered only recently by the Centre, when queried by the Supreme Court on how Aadhaar authentication failure issues were being handled.

India Legal put some pointed questions to Nadhamuni. His answers were almost standardised corporate jargon. He said in his e-mailed reply: “Aadhaar Bridge provides AUA/KUA services as per Section 16 of the Aadhaar Act. UIDAI does not share biometric data with anybody be it Govt or private entities. UIDAI does not allow AUA/KUAs to change Aadhaar CIDR database details. UIDAI has clear guidelines on privacy and security that we rigorously follow.”

He also said that all thoughts regarding security were “incorrect assumptions”. His argument was backed by the statement that “while a government committee had initially decided on collecting only four kinds of basic information—name, address, gender and date of birth, with even e-mail and mobile number being kept as optional—a government-appointed biometric committee decided that 10 fingerprints, two irises, and a photo of the face were needed to accurately de-duplicate the entire population and issue a unique ID.”

It can be inferred that while the original minimalist approach was taken “in order to protect the privacy of the people”, the later development virtually put paid to that idealistic approach.

How does the company facilitate the authentication? In Nadhamuni’s own words: “…the Aadhaar holder can now authenticate herself by entering her Aadhaar-number (user-ID) and one of the demographic/ biometric details (password).”

While this may sound quite like logging into one’s e-mail account, the input values are supposed to be secret. Even if one uses a web keyboard, it is possible to trace back keystrokes for text inputs. For other biometric inputs, such as iris or fingerprint, data can linger in cache files. More important, unlike accessing a bank of e-mails, these sets of biometric data can ultimately lead to a real bank account.

Sean S Costigan, a New York-based strategist and technologist in diverse security and technology fields including cybersecurity and foresight, looks at this from an American point of view and sees similarities.

Replying to an e-mailed questionnaire, Costigan says: “Unfortunately, the State (and by that I mean most all modern national systems of governance) has not shown itself to be a particularly good steward of secret and sensitive information.” (see box for interview)

The Bigger Picture

Reacting to the entire issue, Sean S Costigan (pictured facing page), New York-based strategist and technologist in diverse security and technology fields including cybersecurity (he has led research teams as professor at Harvard and MIT), told India Legal: “Unfortunately, the State (and by that I mean most all modern national systems of governance) has not shown itself to be a particularly good steward of secret and sensitive information.”

“This, despite the state’s mandate to keep people secure and the abundance of procedures and systems designed to grapple with the data it generates and is reliant upon. The reasons for these are varied, but always boil down to uncertainty, change, and failure to anticipate. Other nations are happy to plunder data, including PII, from government databases, as we saw here in the United States with the OPM and Equifax breaches.”

[In June 2015 data of four million people was stolen from the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM). The final estimate of theft was approximately 21.5 million, including records of people who had undergone background checks, though not necessarily government employees. Data stolen included Social Security numbers, names, dates and places of birth, and addresses. The point to note is that the attacker posed as an employee of KeyPoint Government Solutions, a subcontracting company.

Equifax, a consumer credit reporting agency, suffered a massive security breach last May. It has been said that Equifax knew its vulnerability, but did not take protection, resulting in the subsequent release of personal data of more than 800 million individual consumers and more than 88 million businesses worldwide.

Costigan continued: “Years of underfunding have not made the task any easier. So again, the State is behind the curve on security. The analogy I use is to programming: the State was the original full stack security model, dealing with all manner of threats and providing protection for its citizens. With cyber and other long-term hidden in plain view challenges, and the global span of stealthy assaults, the state has lost its way.

“Enter private corporations, which promise the world but can only deliver on what they know and—to be blunt—some won’t even do that. If the final arbiter for proper security is money and contracts, and not loyalty to a higher cause, then we should not wonder why such systems are bound to fray.”

Regarding the overall idea of Aadhaar, though, Costigan shows hope. He says: “Aadhaar shows great promise still. In the United States we have a patchwork of identity authorities, both government and corporate, and regulations and guidelines around personal information and yet that complexity only seems to increase security risk. Accepting my critique of the State and its shortcomings on cybersecurity does not curtail the chance for positive change that India has undertaken.

“To be sure, the system is a massive target and people should count on breaches. It’s like they say about motorcyclists: there are only two kinds, those who have had an accident and those who will.

“The key though, is planning for what is likely and planning for resilience to make sure that faith in the system isn’t reduced.”

—Costigan is the Director of ITL Security. He consults and teaches on cybersecurity and international affairs globally. He also leads a NATO sponsored effort on cybersecurity education and is co-chair of the Economics of Security Study Group.

He hits the nail on the head when he says: “If the final arbiter for proper security is money and contracts, and not loyalty to a higher cause, then we should not wonder why such systems are bound to fray.”

Costigan is not against a system that Aadhaar can provide, with multiple linkages and an almost 360-degree view of the world of a person. Such a system would be the first in the world and even in the US there is no more than a “patchwork” of systems providing data. However, the world is watching to see if security breaches are something that can be handled by this system.

In a later talk, Costigan also pointed out how dangerously simple people data can be used, vis-a-vis the Facebook (and US elections) issue. Artificial Intelligence can analyse very basic data on choices indicated in posts and in click-through records. These, then, can be used to identify political and financial preferences with political and marketing strategists being able to place ‘products’ in place for best effect. How much more can be achieved in deep data mining with AI of vital biometric information is anybody’s guess.

Ravi Shankar Prasad, the Union minister for law and justice and electronics and information technology, has been shouting hoarse from rooftops, alleging that the Congress had a deal with Facebook in electioneering. Congress spokesperson Randeep Singh Surjewala has made counter-claims that the BJP was hand-in-glove with Facebook, doing the same.

The allegations point towards one very critical aspect: if an information aggregator wants to, it can sort and use vast amounts of information towards reaching goals that were unforeseeable even in the recent past. Similarly, the overall picture of Aadhaar Bridge is excellent. It plans to act as authentication pointsman at multiple payment portals and link an array of businesses, without the hassle of repeated representations to different authentication centres. Business can have seamless payment protocols, which is one of the key problems in India in increasing turnover and revenue. Similarly, documentation problems would be ironed out in the same process. That is the big picture. But the data highway in India is as potholed as its roads, as treacherous and porous. The goodness of technology can always be undermined.

“Aadhaar ecosystem poised for disaster”

Pavan Duggal, the top lawyer specialised in the field of cyber law, e-commerce law, etc spoke to India Legal on the complexities of the system and its pitfalls

The entire Aadhaar ecosystem has been built in a tearing hurry by the government, resulting in no legal oversight, he said. “Not only is there no legal oversight, there aren’t even related laws in place to govern activities and deals within the system. It is basically a lawless place. That also makes it a scary place.

“The fact that Aadhaar was initially devised to provide subsidies to the poor, especially to BPL families to avail of entitlements, bypassing intermediaries to avoid corruption, was reason enough to not think of a new law to govern one very positive development initiated by the government,” he said. “When the next government started linking Aadhaar to all and sundry services, the situation changed and no legal oversight meant lawlessness. It is now like a house of cards, ready for a disaster.

“The fact that Aadhaar was initially devised to provide subsidies to the poor, especially to BPL families to avail of entitlements, bypassing intermediaries to avoid corruption, was reason enough to not think of a new law to govern one very positive development initiated by the government,” he said. “When the next government started linking Aadhaar to all and sundry services, the situation changed and no legal oversight meant lawlessness. It is now like a house of cards, ready for a disaster.

“What I think is that we are playing with fire here. India does not have a data protection law, or any related law for that matter,” he said. He also said that when the privacy and linkage issues related to Aadhaar are still being heard in the Supreme Court, it should be natural for the government to wait.

He said that this is how and why the Reliance Jio data theft happened in which one person in Rajasthan called Imran Chippa, a Bachelor of Computer Science dropout, set up a website called Magicapk.com and claimed to be able to provide data of Reliance Jio mobile users. The extent of the breach is yet to be ascertained, but with Reliance Jio’s subscriber base of around 120 million, this could be the biggest data breach in India so far. However, the important thing is that it happened and there are no special laws that can pin the culprit down or help enable setting up of firewalls,” said Duggal. “Dealing with data breach is a legal problem today.”

That is where the problem with Aadhaar Bridge is likely to happen, he said. “As of today, even a school dropout can easily hack into the Aadhaar system. What is stopping him or her from moving in further and into related links?”

He also said that any private association with any government agency where sensitive data is kept has to abide by special laws. These laws are not in place, and the existing laws do not address the issues well.

These are issues of compensation in the case of data theft and what legal assurance a person has regarding his or her data being kept a secret with the government.