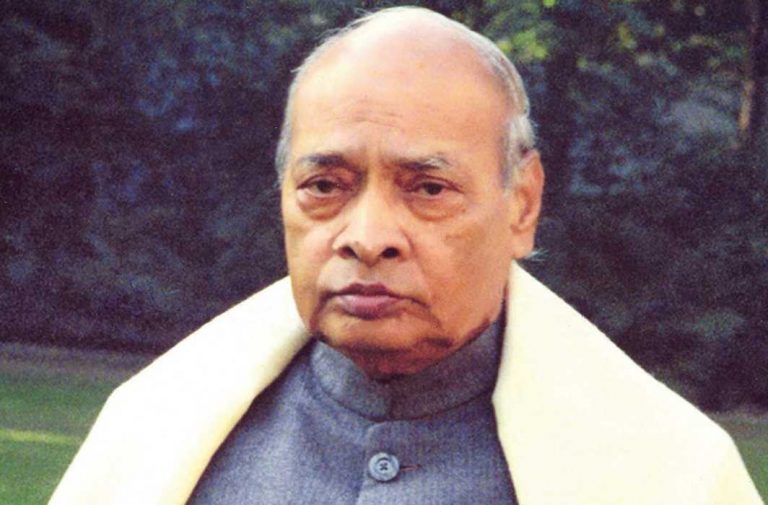

Even as the centre gropes for a coherent policy to tackle exploding Kashmir, it can learn lessons from former PM Narasimha Rao’s diplomacy which won the confidence of Kashmiris and kept the dialogue going with Pakistan

~By S Narendra

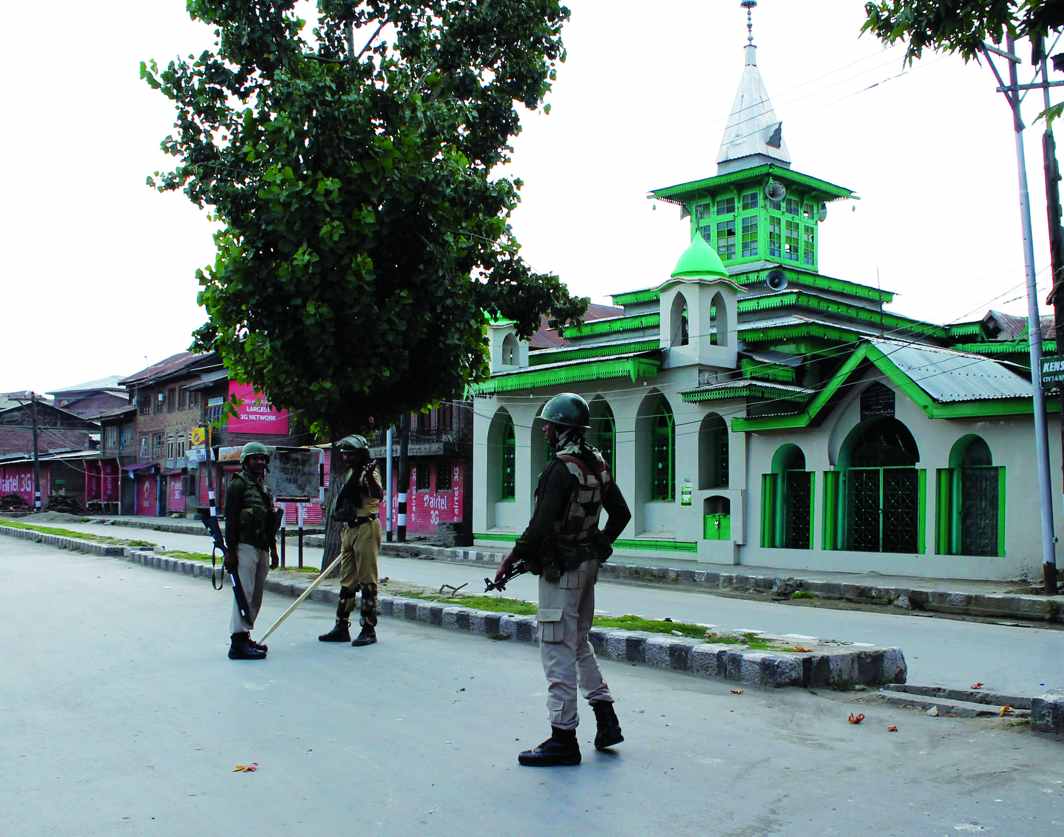

The holding of elections to three parliamentary seats from J&K in 1996, followed by state assembly polls in September-October were both considered a political masterstroke in bringing normalcy back into the militancy hit state.

Barely six years earlier, a parliamentary delegation that visited J&K for assessing the security and political situation there, came to the conclusion that India had lost the state to gun-wielding separatists. The sea change that occurred was not due to any witchcraft but adroit statecraft and a calibrated three-year-long quiet internal diplomacy. The Chanakya behind this transformation was none other than the so-called “indecisive” prime minister, PV Narasimha Rao.

The PM faced several setbacks but he persevered. For example, when he was to make a critical broadcast announcement over AIR and Doordarshan laying down the government’s approach to restoring autonomy to J&K, the officials goofed up. This broadcast on November 4, 1995, now famously referred to as “sky is the limit (for J&K autonomy) but within the Indian constitution”, had to be made from Burkina Faso in Africa which Rao was visiting. The TV cameraman who recorded the broadcast had forgotten to insert the recording tape!

Then, in early 1995, terrorists occupied the Charar-e-Sharif holy shrine situated in a crowded neighbourhood of Srinagar. There was a two-month-long stand-off between the well-armed terrorists and the Indian security forces. On May 10, the terrorists set fire to the shrine, compelling the security forces to counter-attack. They succeeded in whipping up anti-India protests and reversing a normalising situation. A similar terrorist attempt had been made in 1993 by destroying the shopping mall in the capital’s Lal Chowk.

Strategically, Pak-supported terrorists were targeting state political institutions and leaders in order to scare the latter from participating in reviving the democratic political process preceding any election. During a parliamentary debate on the incident in May 1995, almost all parties opposed the conduct of assembly elections.

The PM’s response to this opposition was measured, conciliatory and filled with humility. But he reaffirmed his commitment to ending President’s Rule sooner but through the process of democratic dialogue. For sending an unequivocal message to separatists and their patrons everywhere, Rao engineered the introduction of a parliamentary resolution by the opposition declaring J&K as an integral part of India.

In Rao’s opinion, the prolonging of President’s Rule in J&K was proving counter-productive. It could help Pakistan revive its case for a plebiscite.

Not many remember the “weak PVN” declaring in parliament that India had not forgotten its “unfinished business” in J&K, a reference to India’s claim for Pak-occupied Kashmir. This was a riposte to statements from Islamabad that it would wage 1,000 years of war for wresting J&K.

Surprisingly, Narasimha Rao began his moves for dealing with the J&K problem when he was in the political dog house weeks after the Babri Masjid demolition on December 6, 1992. A routine political affairs committee meeting had ended late in the evening around the end of the year. Among other things, the PM directed the concerned officials that the centre and the J&K government should spare no effort in ensuring adequate supplies of essential items like fuel and food to people during the coming winter months. He also signalled that development works should not be stalled by budgetary constraints or by militant activity.

After the meeting, he confided to some of us that he was keen to revive the democratic activity in the state, He directed me to work towards reviving the state media outlets that had come under both government and militant pressure.

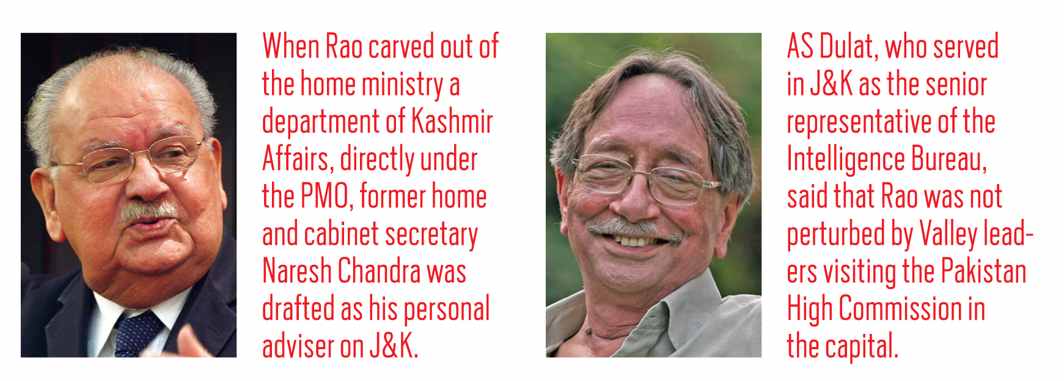

An important signal went out when he carved out of the home ministry a department of Kashmir Affairs that was made to work directly under the PMO. Former home and cabinet secretary Naresh Chandra was drafted as his personal adviser on J&K. Another close confident, Rajesh Pilot, was made MoS in charge of this new set-up. Pilot was given the freedom to open new channels of communication with anyone in J&K who was willing to talk to the government. Previously, only the intelligence wings were communicating with the agitating Kashmiris.

The MoS in the PMO, Bhuvanesh Chaturvedi and the PM’s secretary, KR Venugopal were entrusted with the task of undertaking frequent visits to the state (accompanied by secretaries of development departments) for nudging the state officials to implement key development works. Both the minister and Venugopal were free to meet not only officials but also ordinary people in different parts of the state and hear their grievances and demands.

During some of the meetings, people openly complained about corruption in the bureaucracy and their use of militancy as an excuse not to deliver development. It was extraordinary to hear people suggesting that the government should look at providing solar power to isolated habitats and their willingness to work for building roads to their villages. Plans were also initiated for opening new routes for bypassing Banihal tunnel, prone to blockage by snow and new railway lines to the state.

The low-profile, step-by-step initiatives were never in the limelight, yet probed many fronts for opening doors there and closing it for Pakistan and its proxies. In Rao’s opinion, the prolonging of President’s Rule in J&K was proving counter-productive. Besides undermining India’s democratic credentials, it could help Pakistan to revive its case for a plebiscite.

In early 1993, restriction on foreign media from visiting the Valley for reporting was relaxed. Expectedly, the initial flood of reporting was critical but soon, such reporting also focused on the prevailing violence and disruption of ordinary people’s lives.

The opening of the locked-down state to media was followed by permitting foreign diplomats to visit the state. The militants had not only silenced the state media but the entry of outside newspapers had also been blocked. A special effort was made to make available such newspapers to opinion-makers and others in the state.

BBC and Charar-e-Sharif

While the government had given clear instructions to avoid storming the shrine, the media house reported otherwise

It was a holiday. I had attended a meeting in the PM’s house reviewing the situation created by the takeover of the holy shrine of Charar-e-Sharif by terrorists. Almost in every situation review meeting, the government’s directive to the security agency chiefs was to avoid storming of the shrine as well as prevent civilian causalities. The strategy was to wear out the terrorists and not provoke them to destroy the shrine.

What was unsaid was that there should not be a repeat of Operation Blue Star of 1984.

I was watching BBC news late in the afternoon. To my shock, BBC announced that Indian security forces had stormed Charar-e-Sharif. The BBC correspondent, an Indian, in a voice-over described the attack on the shrine and compared it to the storming of the Golden Temple in Amritsar during Operation Blue Star. I immediately contacted the home ministry’s control room but the officer there had no such information. BSF forces deployed in the outer perimeter of the shrine had not moved an inch, according to the BSF chief.

My calls to the BBC office in Delhi were not answered. As the spokesperson of the government, I directly contacted BBC London. On my insistence, a senior official came on line. I told him that the BBC news was not only incorrect but could lead to riots and untold violence across India causing loss of lives, and India would hold BBC responsible for the untoward happenings. I demanded that BBC immediately carry my denial, if necessary by breaking into their normal programme. I also told him that India would be forced to take this up at the diplomatic level.

After dithering a bit, the official asked me to give him a few minutes and promised to call me back. Within minutes, the head of BBC India, Andrew Whitehead, called me from an STD booth in Agra. He had married a few days earlier and was on his honeymoon. Profusely apologising, Andrew asked me whether I was officially denying the story. When I confirmed my denial of BBC’s story, he promised to get the story out as soon as possible.

As I put down the phone, BBC London called me to assure me that they would immediately correct the story. And within minutes, BBC put out my denial.

Three days later, the terrorists who had captured the shrine started a big fire inside the shrine and also started firing at the security forces cordoning it in order to create a diversion and their leader, Gul Mast, escaped. Security forces were thus compelled to return the fire. The wooden structure of the shrine was burnt down and the cross-firing claimed innocent lives and damaged civilian property. According to most reliable versions, the Indian security forces had exercised maximum restraint and had not stormed the shine.

The prime minister was active in soliciting the assistance of opposition leaders and parties’ in reviving the political process in the state. His own Congress party office was locked. Rao wanted his state party chief (Rasool Kar) to lead the process, but he was mortally scared of becoming a target of militants. In several rounds of meeting with the opposition, the latter advised against holding assembly elections until the return of normalcy in the state. It was obvious that political leaders were unprepared to risk their own or their party workers lives. Many even argued that even if elections were eventually held, there could be very low voter turnout. Rao’s poser to such apprehensions was whether no poll was a better option than low poll. He offered top-level security protection to any leader wanting to tour the state.

Both the militants and Pakistan had succeeded in enlisting the support of international human rights organisations. But they tended to focus only on the alleged abuse of human rights by Indians forces, ignoring the violence perpetrated by militants on ordinary people. Amnesty International was in the forefront of this campaign.

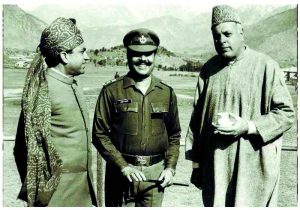

The prime minister took the opportunity of a Delhi conference for setting in motion efforts to set up the Indian Human Rights Commission. This came into being through a Presidential Ordinance in October 1993. Headed by a retired chief justice of India, the Com-mission proactively began to address complaints of human rights abuse. In a brilliant diplomatic move, the prime minister persuaded then opposition leader, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, to lead a delegation (that included National Conference leader Farooq Abdullah) to the UN Human Rights Commission’s 50th session in Geneva. Here, Pakistan, with the support of the US, was debating human rights issues, including their alleged abuse in J&K. The delegation presented a united front and succeeded in beating back Pakistan’s efforts to corner India.

Not many remember the “weak PVN” declaring in parliament that India had not forgotten its “unfinished business” in J&K, a reference to India’s claim for PoK.

Encouraging opposition leaders to engage in parleys with the Valley’s separatist leaders and receiving their feedback for tweaking his approach added to Rao’s strength. The leaders of separatist movement were released in batches for facilitating their dialogue with opposition leaders and other go-betweens. AS Dulat, who served in J&K as the senior representative of the Intelligence Bureau, in his book Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years records that Rao was not perturbed by Valley leaders visiting the Pakistan High Commission in the capital. According to him, Rao had said “if they want to go there (Pakistan High Commission), let them. It’s no big deal”.

Often people talk about confidence-building measures (CBMs) for bringing separatists to the conference table. Here was an example of how to use CBMs without much ado and anticipating demands for CBMs by people feeling alienated.

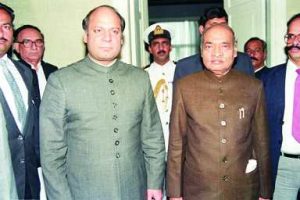

The prime minister’s internal diplomacy was matched by his external outreach. Despite continuous hostile acts and noises coming from Pakistan, Rao did not let go of opportunities to meet Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif at international meets such as the UN General Assembly (UNGA). In fact, the two prime ministers met six times. After the last such one-on one meeting in 1995, Rao told some of us that his counterpart had hinted to him that he was unable to deliver on of any of the mutually agreed key points (India had presented “non-papers”).

Rao’s willingness to keep the dialogue door open with Pakistan despite its attempts to sabotage the revival of the political process in the Valley had conveyed a positive message to the Kashmiris. According to the prime minister, the then US ambassador to India, Frank Wisner, who visited J&K in early 1996, had told him that the Valley people were fed up of militancy and given a chance, they would come out to cast their ballots. He had also conveyed that ordinary people were not inclined towards Pakistan.

I was a member of the prime minister’s delegation to the UNGA (its 50th anniversary) in November 1995. On the plane returning to India, he sent for me. Among other things, he brought up the subject of preparing for J&K assembly elections as well as the general elections. In a musing mood, the prime minister remarked: “It is time my party and others think of bringing fresh leaders in the state. It is going to be a long haul.”

When eventually the assembly elections were held in September, Rao was succeeded by HD Deve Gowda. The National Conference under Farooq Abdullah, which had boycotted the parliamentary polls held earlier, now participated in the state poll only after the new PM reiterated Rao’s pledge to accord maximum autonomy.

—The writer was former Principal Information Officer

and served as Information Adviser to the PM