Above: Former SC judge J Chelameswar/Photo: Anil Shakya

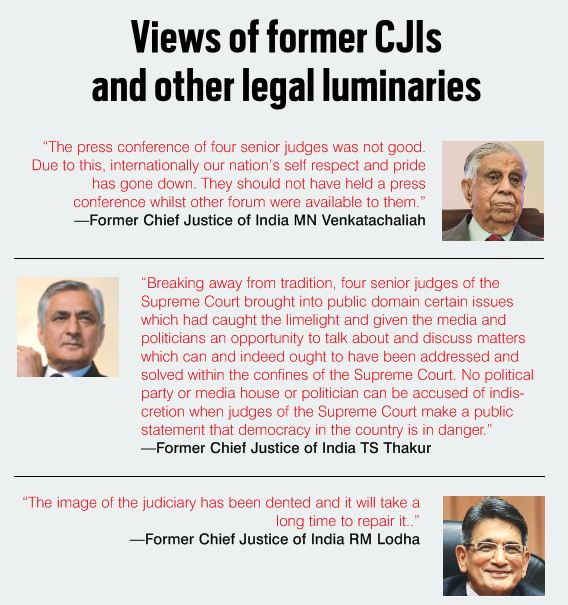

The question several judges and legal luminaries are now still pondering about is whether Justice Chelameswar should be lauded as a whistleblower who espoused a cause higher than his own personal ambitions, or as a person engrossed in pursuing a private agenda

~By India Legal Bureau

Comparisons are easy to make. They can also be far-fetched. One obvious one is placing former law minister Shanti Bhushan side by side with the late Justice Hans Raj Khanna and Justice Jasti

Chelameswar. It is like weighing a pebble against a mountain. Justice Khanna stood like a wall of granite against the might of the Indian state which was privatised for personal gain by the politico-bureaucratic machinery that suspended all liberties under Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. This would be chief justice resigned rather than compromise with the Constitution. Justice Chelameswar, the second seniormost judge in the Collegium, retired when his term ended after a controversial innings that brought both opprobrium and politics to the Supreme Court.

Justice Chelameswar may have spoken his mind and ruffled feathers but none of his judgments during these troubled times, when intolerance and authoritarianism hang heavy in the air, can light a candle to Justice Khanna’s judgments which form the basis of modern constitutional law in India.

The question several judges and senior legal luminaries are now still pondering is whether Justice Chelameswar should be lauded as a whistleblower who espoused a cause higher than his own personal ambitions, or a person engrossed in pursuing a private agenda. Actually, he shot into the limelight not because of any earth-shattering judgment that would alter the course of Indian jurisprudence but because he played host at his house to an unprecedented January 12 press conference. Joined by Justices Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph—who then formed the Supreme Court Collegium that appoints judges—the foursome levelled a direct frontal assault on the chief justice of India (CJI) for allegedly assigning case rosters in an ad hoc fashion.

He hit the headlines again when a conveniently leaked letter from him dated March 21 addressed to the CJI and 22 other Supreme Court judges became public. The latest salvo called for unity in resisting what is being seen as another blatant attack on the judiciary’s independence.

While India Legal has been persistent and consistent in defending and fighting for a Judiciary free of Executive interference and control, the magazine has frequently also been critical of the Judiciary when it has made itself vulnerable to even the appearance of manipulation.

In top judicial circles, the four-judge “mutiny” has been simultaneously hailed as a much-needed courageous step and denounced as irresponsible and creating a breach into which the Executive can step in without resistance. Whispers grew louder that Justice Chelameswar was creating a small window for himself to fulfil an old ambition—to become CJI if even for a short period before his retirement.

Sources close to him say he carried a lingering grouse that he had been rob-bed of his chance to become CJI in a seniority system followed by the Collegiums. His supporters claimed that after Justice JS Khehar retired in August 2017, the CJI post should have gone to Justice Chelameswar and not Justice Dipak Misra. They reasoned that the former had become a High Court chief justice in 2007—two years before the latter became a High Court chief justice—before both were promoted to the Supreme Court in 2011.

According to a well-established Collegium precedent, however, seniority in the higher judiciary is determined from the date that a judge takes his oath in the High Court. The record clearly shows that Justice Misra became a judge in the Orissa High Court on January 1, 1996, while Justice Chelameswar was elevated to that position in the Andhra Pradesh High Court on June 23, 1997, thus clearly establishing Justice Misra’s seniority.

It was small wonder that Justice Chelameswar was the sole dissenter in the constitutional bench which negated the legislative creation of the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). He opened himself to the criticism that because of a personal resentment, he had sided with a new law which would have completely thrown open the door to the Executive to control appointments to the Judiciary—especially the Supreme Court.

It is for this reason that members of the judicial community found his “rebellion” and “letter” in defence of judicial independence personally motivated and even hypocritical. The talk that Justice Chelameswar was bent upon sidelining Justice Misra (who retires in October) gained further momentum when allegations were made that the former had drafted the language of the widely publicized impeachment letter against CJI Misra and it was given to a “public interest” lawyer who then circulated it to obtain signatures.

This further vitiated the atmosphere in which politicians from both parties began to view the Supreme Court as a political football. Justice Chelameswar found himself at the receiving end of barbs, once directed against Justice Misra, that he was indulging in politics. His detractors began raking up the past. He was accused of being in touch with top BJP leaders during the NJAC debate in order to block the elevation of Justice Misra to the top post.

When that did not succeed, Justice Chelameswar’s supporters, many of them playing a double game, gave him the hope that if the aborted impeachment motion came to the House, the CJI would have to recuse himself until its final disposition, and he could then become the acting CJI.

That scenario did not work out either. In the end, a sulking Justice Chelameswar refused even to attend a traditional farewell party in the Supreme Court. But he was hardly silenced. He gave post-retirement interviews to selected media houses and drew sharp flak from various legal organizations and retired judges.

In one statement, he said: “Some-times administration of the Supreme Court is not in order and many things which are less than desirable have happened in the last few months.” Unless this institution is preserved, “democracy will not survive” in this country, he added, stunning the nation. Many felt that Justice Chelameswar could have avoided this act and instead, written a personal letter to the president about these issues and leaked that letter to the press, thereby saving the image of the Judiciary.

The Bar Council of India responded: “Such statements and comments are liable to be deprecated. Such statements cannot be tolerated, accepted or digested by the advocates including the rest of the countrymen.” It was also signed by four other office-bearers of the BCI.

Other critics aver that Justice Chelameswar may not be the knight in shining armour his diehard supporters have been projecting because he went along with several Collegium decisions which seemed blatantly unfair or biased.

Perhaps the most blatant case in recent years was that of Karnataka senior judge Jayant Patel. Just before his timely elevation as chief justice was due—and he was found qualified even for a Supreme Court position—he was summarily transferred to the Allahabad High Court in a decision made by the Collegium. This was not the first time. This was the same judge who had ordered a CBI probe in the “fake encounter case” case of Ishrat Jahan when he was at the Gujarat High Court. Then too he was transferred to Karnataka just before his promotion as chief justice. On both occasions, powerful associations in Gujarat and Karnataka threatened agitations and openly accused the Collegium of bending before the wishes of the Dilli Durbar.

As one senior lawyer put it: “One cannot use double standards. After all, Justice Chelameswar was very much in the Supreme Court then. Why did he not talk about the independence of the Collegium then?”

Very often, personal prejudices override the compulsions of merit in the appointment and elevation of judges. The iconic judge AP Shah, former chief justice of the Delhi High Court and Law Commission chairman, could not make it to the Supreme Court because of personal opposition from Chief Justice SH Kapadia.

Another lawyer of eminence, Gopal Subramaniam, who was also headed for the Supreme Court along with Rohinton Nariman, AK Goel, and Arun Mishra, was stopped dead in his tracks by a blizzard of bad publicity engineered in the press about him by the Executive branch.

Subramaniam threw in the towel: He asked his name be withdrawn rather than face what his supporters say was a dirty tricks campaign. These same supporters also secretly wonder whether the Collegium could have been more active in championing his cause.

While there are those who openly praise Justice Ranjan Gogoi for his role in the “four-judge mutiny” staged at Justice Chelameswar’s house, others contrast this with the former’s treatment of Justice Markandey Katju, a former Supreme Court judge. In an unprecedented move, he was served a contempt notice and personally summoned by a bench headed by Justice Gogoi because of his outspoken criticism of judicial behaviour in a controversial case.

Justice Chelameswar also caused a flutter when he refused to hear a petition calling for a new system of rostering instead of the chief justice assigning cases. He said he was about to retire and didn’t want “another reversal” of his order within 24 hours. “You know my difficulty, you understand my problem,” the judge said when lawyer Prashant Bhushan asked him to take up the petition by his father Shanti Bhushan. But insiders indicate that Justice Chelameswar was fully aware in advance that this matter would come to him, and his stance was merely “role-playing”.

Another allegation against him is that he was not apolitical. During his press conference, CPI’s D Raja dropped in to meet him, leading to raised eyebrows. However, Justice Chelameswar said he was an old friend and had just dropped in seeing the huge media presence outside his house that day.

The CPI also clarified that D Raja had paid a visit to Justice Chelameswar in his personal capacity and not as a representative of the party. “Raja went (to Justice Chelameswar’s residence) in his personal capacity, not as a representative of the party,” CPI general secretary S Sudhakar Reddy said. D Raja too said that he paid a visit to the Supreme Court judge as he knew him from his student days.

But insiders insist that Justice Chelameswar often provided access to law enforcement officials, politicians and certain lawyers for informal interactions and also approached four former CJIs regarding the transfer of High Court judges. And, sources confide, he was not above helping out friends. They cite the cases of Justice Chelameswar taking interest in delaying a sensitive case of a chief minister whom he visited in the All India Institute of Medical Sciences where he had been hospitalized, as well as a case of sexual harassment involving the brother of a sitting Supreme Court judge when he (Justice Chelameswar) was chief justice of the Gauhati High Court.

Incidentally, he is the only SC judge to have a heavy vehicle driving license.

Another grouse against Justice Chelameswar was that he had retired without hearing many petitions. In many of the cases, arguments had been carried out but judgments were pending.

During his tenure in the apex court, he took quite a bit of leave due to which cases had to be heard by a single-judge bench. He was infamous for his chronic absenteeism, often taking long family vacations and using the maximum perks allowed to a judge.

When he was chief justice in Guwahati, he made a family trip to Kolkata and was dissatisfied that the Calcutta High Court protocol department did not do any extra running around or pamper him up to his expectations. In retaliation, he ordered that the protocol department under the jurisdiction of the Gauhati High Court should deny all help and facilities to their Calcutta counterpart. Some judges staying in a VIP guest house in that area were requested to vacate.

One of the “perks” he allegedly availed of was a gift of two captured elephants from the wilderness, which were gifted then to temples. A case is still pending “against unknown persons” under various provisions of wildlife preservation laws.