With lawyers charging exorbitant fees and frivolous appeals delaying cases routinely, a majority of litigants find that their quest for justice can be a very expensive one. Is there a way out?

~By Usha Rani Das

“India has acquired a reputation of an expensive legal system. In part, this is because of delays but there is also a question of affordability of fees. The idea is that a relatively poor person cannot reach the doors of justice for a fair hearing only because of financial or similar constraints while it’s in our constitutional values and republic ethics. It is a burden on our collective conscience.’’

—President Ram Nath Kovind, on November 25, National Law Day

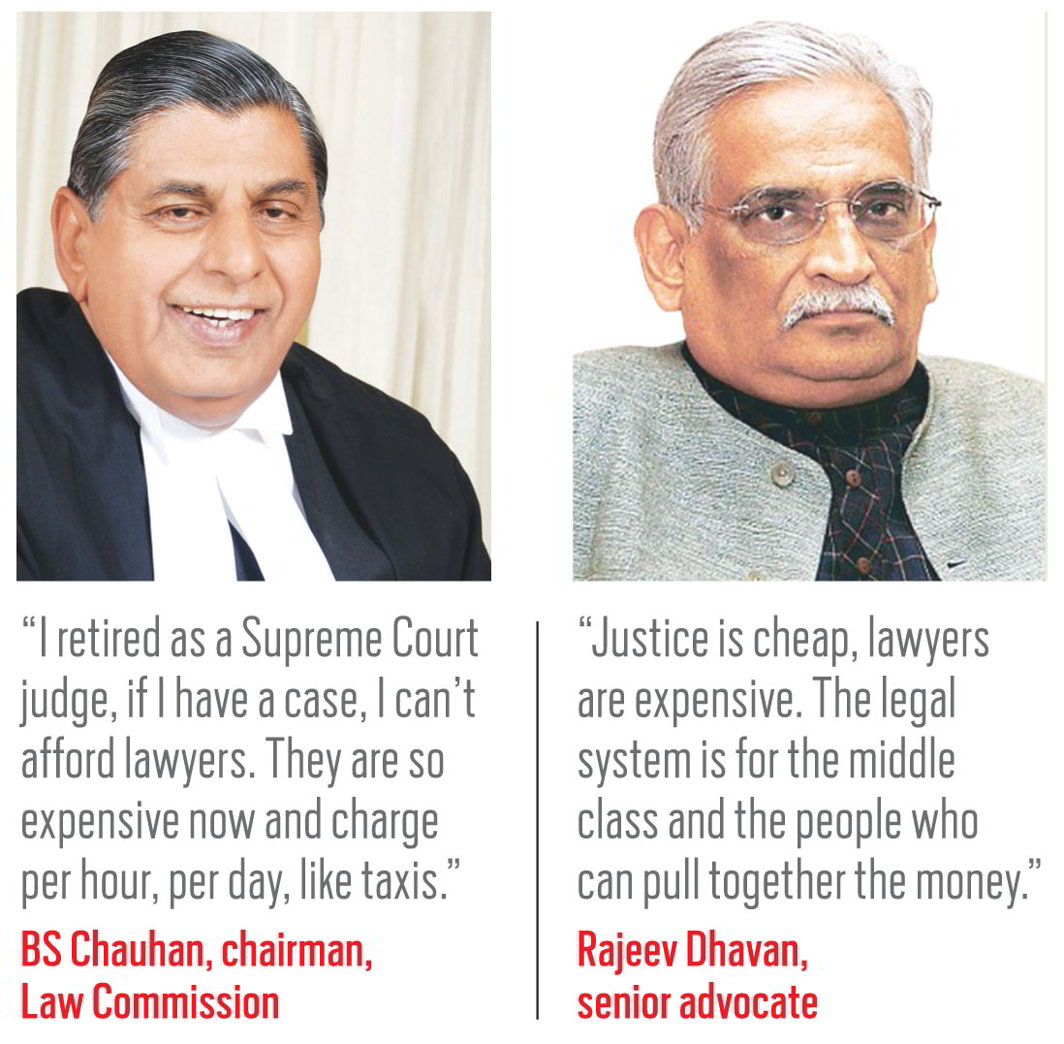

The “burden’’ that the president talked about may be to do with our collective conscience but it is also the financial one that a majority of litigants has to bear when they find themselves entering India’s complex judicial system. Kovind should know: he was a practising lawyer until 1993 before he got into politics. It is quite ironical, literally a travesty of justice, that a poor country like India is saddled with such an expensive legal system. Much of that is to do with the fees that lawyers charge. Law Commission Chairman BS Chauhan, speaking at a seminar last September, said: “I retired as a Supreme Court judge. If I have a case, I cannot afford them (lawyers). They are so expensive nowadays and they charge per hour, per day, like taxis.”

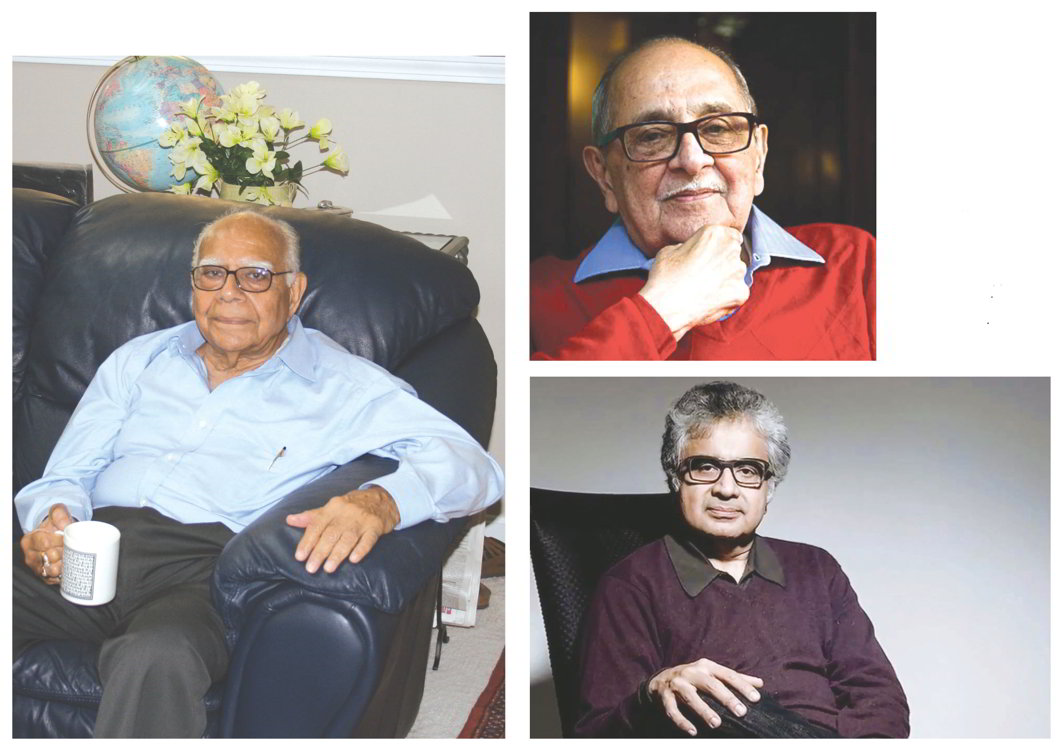

Last July when celebrity lawyer Ram Jethmalani and his client, Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, had a falling out, he quit as counsel and promptly sent his client a bill of Rs 3.5 crore which, he said, was a reduction of his normal legal fees. “I have given a discount, I have not asked for the retainer fee I normally charge my other clients,’’ he said. Jethmalani had originally offered to appear virtually pro bono but once lawyer and client differed on the case being heard in the Supreme Court, he changed his mind and presented a bill which included Rs 22 lakh per appearance in court. This, he declared magnanimously, was also minus what he would charge for client conferences.

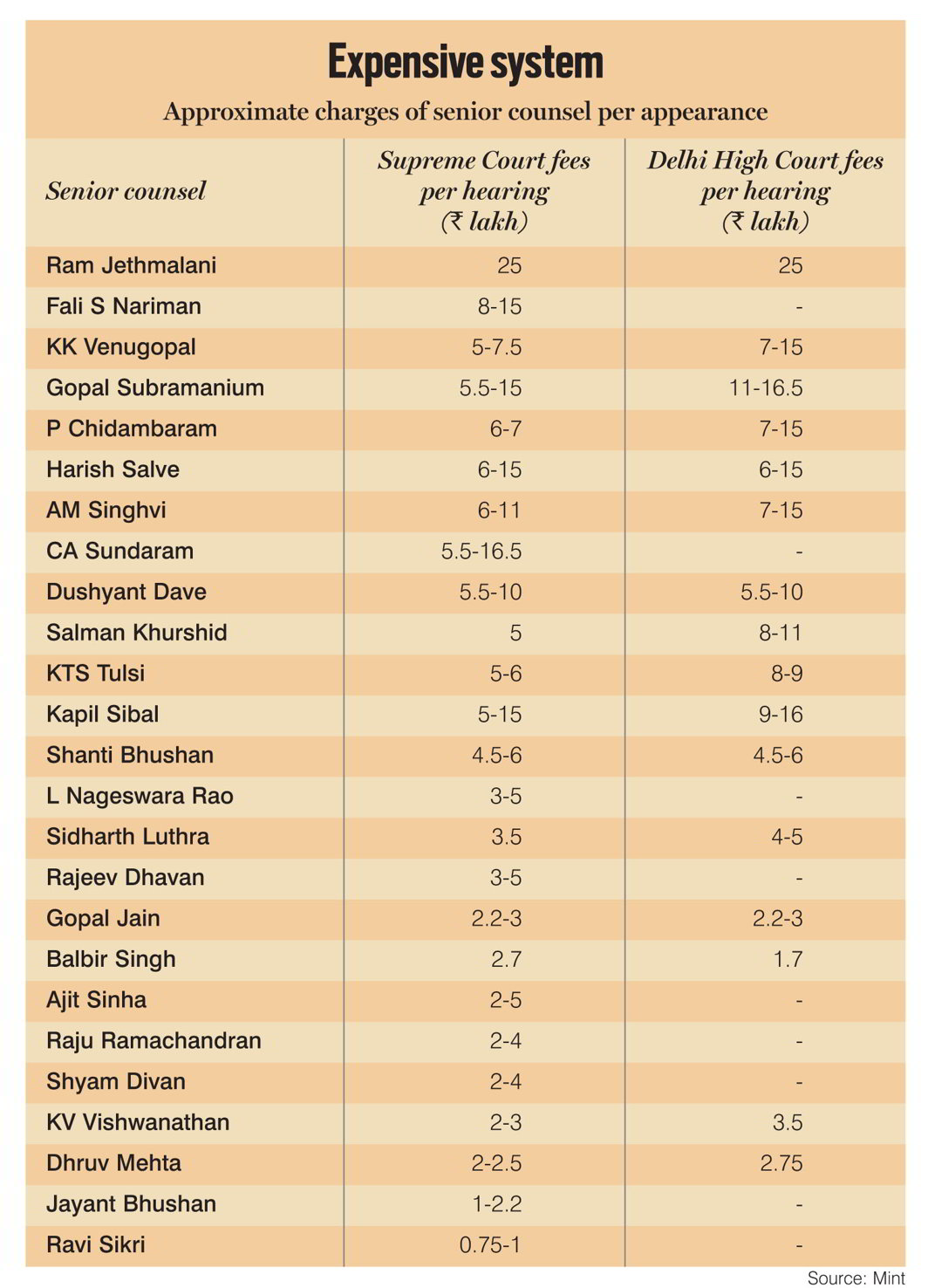

He, along with Harish Salve and Fali Nariman, occupy the top spots when it comes to fees charged but there are a host of other legal eagles who charge between Rs 5 lakh and Rs 15 lakh an appearance (see box 1). The costs vary from client to client. If the client is in Mumbai, a Delhi lawyer like Salve or Mukul Rohatgi will charge for business class air travel, stay in a prominent five-star hotel along with their team, and bill for meals and local transport and conference or consultation fees, even if the consultation is over the phone. A handful of senior advocates also charge something called “clerkage” which is 10 percent of the total professional fee. Therefore, if the appearance fee is Rs 5 lakh, the bill will be for Rs 5.5 lakh. Nobody knows whether it goes to clerks, is used for office expenses or spent on a fancy five-star family lunch.

While corporate and affluent clients can afford to spend between Rs 2 and Rs 3 crore on a case, a majority clearly cannot. A survey conducted by Daksh, a civil society organisation, revealed that 90 percent of the litigants earn less than Rs 3 lakh per annum. The study, done in 2015-16, found that civil litigants spent an average of Rs 497 per day to attend court and incurred a loss of Rs 844 per day on account of wages and work time lost while appearing in court—totalling Rs 1,341 for every day spent in court. In criminal cases, the litigant spent Rs 542 per day to attend court and lost Rs 902 per day due to loss of pay and business income, adding up to Rs 1,444. In a broader perspective, he/she loses wages totalling Rs 50,000 crore a year at an average of Rs 1,746 per case per day for attending lower court hearings. After adding the lawyer’s fees, the litigant’s expenses cross Rs 80,000 crore annually, which is 0.70 percent of India’s GDP (in 2015-16).

For many at the lower end of the socio-economic scale, it is a burden that becomes unbearable. Jyoti’s husband earns about Rs 6,000 per month. She, her husband and their two sons travel for 2.5 hours every week to come to the Delhi District Legal Services Authority (DDLSA) to seek a lawyer. They are fighting a property dispute case. It has been three months now since they approached the DDLSA but they haven’t got a lawyer yet. “We spend Rs 400 every week to travel from our village to Delhi. My husband is a daily wage earner. He loses one day’s income for coming here,” she said.

Even when the services of a lawyer are obtained, the problems just keep mounting. It took Rajender Singh more than a decade to finally get justice in his case against the Lt Governor of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Singh was a lecturer and had filed an application for regularisation of his service in 1987. The tribunal at the Calcutta High Court had asked him to complete his MPhil degree and granted him study leave for a period of three years. Though he completed his degree, he was not granted the position by the university. He was asked to approach the tribunal several times unnecessarily. Following this, he was “harassed” by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC), his university authorities and government officials for years before the Court finally provided him relief in 2005.

There are many Singhs in India who struggle for years to get justice. Some fight the case for years, even decades, some lose hope and give up while most don’t even think of coming to court to settle their issues. Expensive litigation, exorbitant lawyer fees coupled with an almost non-existent legal aid system have made one of the world’s strongest judiciary systems inaccessible to the common man. As senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan told India Legal: “It (legal system) is for the middle class and the people who can pull together the money.”

The Supreme Court is well aware of the problem. In Vinod Seth vs Devinder Bajaj, the apex court had observed: “Under no circumstances, costs should be a deterrent to a citizen with a genuine or bona fide claim, or to any person belonging to the weaker sections whose rights have been affected, from approaching the courts.” That judgment was seven years ago and since then the costs have only gone up. As Chauhan said: “Big lawyers can defend any kind of greatest offence.” A “big lawyer” charges anywhere between Rs 2 lakh per hearing and Rs 20 lakh, according to estimates. While Fali S Nariman charges Rs 10-15 lakh per appearance in the Supreme Court, Shyam Divan charges almost Rs 3.5 lakh. KK Venugopal mostly does pro bono cases but also charges Rs 2.5 lakh per hearing.

According to a 2015 Mint report, Jethmalani is one of the highest paid lawyers in India at the Supreme Court, who charges at least Rs 25 lakh per hearing. Former finance minister P Chidambaram charges in the range of Rs 6-7 lakh for one appearance before a bench of the Supreme Court. Former law minister Kapil Sibal charges up to Rs 15 lakh for one appearance at the Supreme Court. Congress politician Abhishek Manu Singhvi, Harish Salve, Gopal Subramanium, KTS Tulsi, Dushyant Dave, Jayant Bhushan also fall in the “big and expensive” lawyers bracket.

If a senior counsel appears outside Delhi, the fee sees a steep rise as the bills for business class or chartered flights and hotel accommodation become an important addition to the fee. Besides, though the litigant pays for the senior counsel to appear in court and fight the case, there is little he/she can do to ensure that the counsel does so.

The system, however, is equally responsible. Dhavan said: “We have to see it at three levels—subordinate courts, high courts and the Supreme Court. They say justice is cheap but civil justice requires a court fee. So, justice is cheap, lawyers are expensive. At the local level, many people cannot afford lawyers. They give up their cases. They take on lawyers who are generally not quite up to the mark. We know there are many tout lawyers. And tout and inferior lawyers can’t give any kind of justice even if they do give cut-price justice.”

The system, however, is equally responsible. Dhavan said: “We have to see it at three levels—subordinate courts, high courts and the Supreme Court. They say justice is cheap but civil justice requires a court fee. So, justice is cheap, lawyers are expensive. At the local level, many people cannot afford lawyers. They give up their cases. They take on lawyers who are generally not quite up to the mark. We know there are many tout lawyers. And tout and inferior lawyers can’t give any kind of justice even if they do give cut-price justice.”

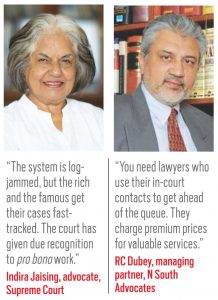

There are numerous reasons why legal fees add up to an exorbitant amount. Ranjeev C Dubey, managing partner of N South, Advocates, told India Legal: “The legal system is not expensive per se. To move the system, you need lawyers who can use their in-court relationships to get ahead of the queue. It’s a valuable service for which they charge premium prices. In addition, since they know what they are charging for, they don’t want to do the slog work. So suddenly, you now need two lawyers. But then who is to make the case winnable? You need a really smart lawyer. So now you are paying for three lawyers. This is how costs add up.”

Sometimes the senior is overburdened by cases and hence cannot always appear at hearings. So, it has become a common trend to engage other seniors as back-up. But in such cases though the back-up lawyer’s fee is usually low, he demands a higher fee.

Further, the lack of competent lawyers makes the system expensive and out of reach of the ordinary citizen. Matthews J Nedumpara, an advocate practising at Bombay High Court, told India Legal: “There is a lack of competent lawyers and the best talents are available to the elite class of people who can afford them.” According to advocate AC Philips, a senior advocate gets elaborate audience, in a preferential manner, for which he charges exorbitant fees, which the common man can’t afford. He told India Legal: “Section 23(5) of the Advocates Act provides for preferential hearing for senior advocates. It means, those citizens who cannot afford the premium fees of senior advocates often have their cases pending for more than a year.” According to the 2017 Doing Business report of the World Bank, the Indian judicial system follows the rules of adjournments (the maximum adjournments that can be given is three) in less than 50 percent of the cases.

Supreme Court advocate Indira Jaising told India Legal: “The system is log-jammed, but the rich and the famous manage to get their cases fast-tracked.” And the “rich and famous” are out of the reach of the common man. The Transparency International Annual Report 2010 said that in India court efficiency is also crucial, as a serious backlog of cases creates opportunities for demanding unscheduled payments to fast-track a case.

The complicated judicial process also makes it less accessible to ordinary citizens. Not everybody can afford to go through the process because the process is itself a punishing one, said Dhavan. When one goes to court and gets an adjournment, he has to pay the lawyer again for the second hearing. Even if the lawyer agrees to do it for a lump sum, there are often hidden costs—like sometimes the clerk too asks for money for photocopying pages and other services.

Besides, quite often the parties file frivolous litigation and appeals continuously in court so that the case never ends. Hence, the petitioner is harassed for years without justice. In Vinod Seth vs Devinder Bajaj, the Supreme Court had observed: “The lack of appropriate provisions relating to costs has resulted in a steady increase in malicious, vexatious, false, frivolous and speculative suits, apart from rendering Section 89 of the Code of Civil Procedure ineffective. Any attempt to reduce the pendency or encourage alternative dispute resolution processes or to streamline the civil justice system will fail in the absence of appropriate provisions relating to costs. There is, therefore, an urgent need for the legislature and the Law Commission of India to revisit the provisions relating to costs and compensatory costs contained in Section 35 and 35-A of the Code.” The same was the case with Rajender Singh who had to approach the tribunal several times due to frivolous petitions from opposing parties.

National Legal Services Authority

National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) was formed to provide free and speedy legal services to the poor. Legal services authorities have been formed in every state and district.

Every person who has to file or defend a case shall be entitled to legal services under this Act if that person is from the disadvantaged sections like SCs or STs, victims of trafficking, beggars, women and children, or the mentally ill or disabled.

NALSA also serves those who are victims of natural disasters, ethnic violence, caste atrocities or industrial disasters. There is a verification process which confirms the applicant’s annual income and status. If the applicant meets the eligibility criteria and has a prima facie case in his/her favour, the Authority provides counsel at the State’s expense. Court fee and incidental expenses in connection to the case are also paid.

India Legal also has a legal aid programme called, India Legal Research Foundation (ILRF). It provides free legal aid to people who are socially and economically backward or who belong to the downtrodden sections of the society. The team of legal experts at ILRF provides them legal advice or opinion. While it does not appoint lawyers, the legal experts make them aware of the appropriate legal procedures to avail legal remedy for their cases.

India Legal‘s sister TV channel, APN, a media associate to ILRF, is also dedicated to providing a platform to supplement the group’s objective of access to justice and justice for all.

President Kovind’s remarks on poor people being kept out of the judicial system were based on his experiences as an advocate when he was part of the constitutionally mandated legal service organisation dispensing free legal aid to those in financial difficulties. However, free legal aid in India exists in theory but rarely works in practice. Article 39A of the Constitution of India provides that the State shall ensure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity, and in particular, provides free legal aid, by suitable legislation or schemes or in any other way, to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disability. Articles 14 and 22(1) also make it obligatory for the State to ensure equality before law and a legal system which promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity to all. For this purpose, numerous legal services authorities were formed.

The problem is they simply don’t work, according to Dhavan. “Whether one is entitled to legal aid is in itself the question. In certain cases, one has to prove that he/she cannot afford a lawyer. The process is so cumbersome that one loses hope,” he said. Deepika Sachdeva, a legal aid counsel, told India Legal that there are cases where the rich also take the help of legal aid services just to avoid paying a lawyer. She said: “Legal aid services are for those who can’t afford to go to court because of the high fees of lawyers. The rich also misuse it. Though 99 percent of cases are genuine, one percent are false. We first check the jurisdiction. We check his/her place of work, nationality, income affidavits, etc. Accordingly, we first counsel the person as a pre-litigation process. We try to solve it through mediation first so that cases do not pile up in court and the person gets quick relief. After that a lawyer is assigned to the person. The process usually takes at the most 10-15 days. The lawyer should give his/her client a day-to-day update of the case.” But people often have to wait for months before they are assigned a lawyer. It rarely happens that they are given a daily update of the case by their respective lawyers.

Ashish Gupta has been coming to the DDLSA for the past seven years. Yet he is not even close to justice. His father was allegedly killed by some locals who then seized his properties. Having lost the only means of income, Gupta and his mother beg on the streets. But they haven’t lost the will to get their shop back. He had filed an RTI on the details of his shop, claiming that the plot was also registered under his grandfather’s name, in September. It has been more than 45 days but he hasn’t got a reply. When he came to DDLSA, he was told to come after 20 days as he had filed the RTI in October. When he stood his grounds, the front office brought out the documents which showed that he had filed the RTI in September. After this, he was asked to come after 10 days. “I have been assigned a new lawyer every now and then. Four lawyers have represented me till date,” he said.

Ashish Gupta has been coming to the DDLSA for the past seven years. Yet he is not even close to justice. His father was allegedly killed by some locals who then seized his properties. Having lost the only means of income, Gupta and his mother beg on the streets. But they haven’t lost the will to get their shop back. He had filed an RTI on the details of his shop, claiming that the plot was also registered under his grandfather’s name, in September. It has been more than 45 days but he hasn’t got a reply. When he came to DDLSA, he was told to come after 20 days as he had filed the RTI in October. When he stood his grounds, the front office brought out the documents which showed that he had filed the RTI in September. After this, he was asked to come after 10 days. “I have been assigned a new lawyer every now and then. Four lawyers have represented me till date,” he said.

When his first lawyer was asked why he left his client after one and a half years, his cold reply was: “He is mentally unstable. They keep on filing false cases like these. We have to assign a lawyer and hence we don’t drop these cases.” Are clients with mental health problems not allowed justice in India? Though Sachdeva said they take into account the mental condition of the litigants, clients at the legal aid services’ centre beg to differ. There are no checks and measures to ensure that the lawyer assigned takes the case seriously and tries his level best to expedite justice in court. Hence, cases end up in court for ages.

The Daksh database currently has details of more than 40 lakh cases pending before various courts. The average pendency of any case in the 21 high courts for which data is available is about three years and one month (1,128 days). For a case in any of the subordinate courts, the average time in which a decision is likely to be made is nearly six years (2,184 days). Assuming that a case does not go to the Supreme Court, an average litigant who appeals to at least one higher court is likely to spend more than 10 years in court. And if one’s case does go to the apex court, the average time increases by at least three more years.

Rich and powerful

The rich use their money to hire the most expensive lawyers who are able to employ their status to jump the queue and speed up delivery. The powerful use other methods. When Neelam Katara (see picture) took on the politically powerful Yadav family over the murder of her son, Nitish, she had little idea of the ordeal she would face. The trial began in 2003, and due to political interference, the UP government had to withdraw the public prosecutor, SK Saxena, from the case. In August 2006, the Supreme Court, responding to an appeal from Neelam Katara, shifted the trial from Ghaziabad to Delhi because of DP Yadav’s considerable influence in the area, including its administration and judiciary.

The rich use their money to hire the most expensive lawyers who are able to employ their status to jump the queue and speed up delivery. The powerful use other methods. When Neelam Katara (see picture) took on the politically powerful Yadav family over the murder of her son, Nitish, she had little idea of the ordeal she would face. The trial began in 2003, and due to political interference, the UP government had to withdraw the public prosecutor, SK Saxena, from the case. In August 2006, the Supreme Court, responding to an appeal from Neelam Katara, shifted the trial from Ghaziabad to Delhi because of DP Yadav’s considerable influence in the area, including its administration and judiciary.

The number of adjournments on frivolous grounds only added to the length of the trial and the costs. As she told India Legal: “The number of adjournments should be monitored. This is how they (powerful families) influence the courts. They think if they somehow keep getting adjournments, the other person would eventually give up and drop the case.” She refused to give up and on October 3, 2016, the Supreme Court of India sentenced Vishal and Vikas Yadav to 25 years in prison. It took Neelam Katara 16 years to get justice for her murdered son. She refuses to reveal what it cost her financially but it was her courage, perseverance and dogged determination to see her son’s killers brought to justice that kept her going. Not many litigants possess those qualities.

The legal aid teams at the high court as well as the Supreme Court are equally weak. Everybody follows “a means test and a merits test”. First, one must establish that he is really poor and this benchmark is facile. Even if one does finally get a lawyer from the legal aid team, the lawyer would discredit the case as an empty litigation despite it being quite litigious, said Dhavan. “We all pretend that there is great legal aid in the country. Even in the Supreme Court, it is very rare that someone from the legal aid team will actually fight the case. So, litigation is a luxurious bridge. It will continue to be so for quite some time,” he added. “No one is satisfied with the services,” said Meenu who is coming to the DDLSA for the past two months in the hope of justice.

Finally, experts also point out that while there are lawyers available the commitment is lacking. The 240th Report of the Law Commission states: “A litigant, who starts the litigation, after some time, being unable to bear the delay and mounting costs, gives up and surrenders to the other side or agrees to settlement which is something akin to creditor who is not able to recover the debt, writing off the debt. This happens when the costs keep mounting and he realises that even if he succeeds he will not get the actual costs. If this happens frequently, the citizens will lose confidence in the civil justice system.”

The judgment on the appointment of senior counsel, Indira Jaising vs Secretary General, in which the Supreme court has held that income is not an issue to be considered in designations will go a long way in creating a pool of competent seniors for these litigants. Jaising said: “The court has also given due recognition to pro bono work which will also encourage many people to do pro bono work and legal aid.” But Dhavan is not very hopeful. “In some states in America, the judicial system says 10-30 percent of one’s practice should be pro bono. What rich firms do is they farm out the legal aid. So, a mention of pro bono is nearly an exhortation. It’s like saying to lawyers, ‘be good’. It doesn’t provide any service.”

For quick relief, National Lok Adalats are organised in the Patiala House Courts. Sachdeva said: “We try to resolve as many cases as possible there. One has to understand that this is not the only work we have. We have other work too.” Though she said that once a case goes to court, it usually takes two-three months to resolve, people like Ashish, Meenu and Jyoti had to wait for months to get a lawyer.

Between expensive lawyers, frequent adjournments and delaying tactics, no litigant ever knows what his legal costs will be till the judgment is delivered and the bill arrives. The classic case was Ashok Kumar Mittal vs. Ram Kumar Gupta where the apex court observed: “The present system of levying meager costs in civil matters (or no costs in some matters), no doubt, is wholly unsatisfactory and does not act as a deterrent to vexatious or luxury litigation born out of ego or greed, or resorted to as a ‘buying-time’ tactic. A more realistic approach relating to costs may be the need of the hour.”

What that approach could be is still in open court.