Illustration: Anthony Lawrence

From the Lokpal to the green tribunal, the Supreme Court and High Courts, institutes of higher learning and even investigating agencies, the vacancies are piling up

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

On April 5, 2011, activist Anna Hazare began the first of three indefinite fasts in Delhi demanding that the UPA II regime must get his version of the Lokpal Bill (called the Jan Lokpal Bill) passed by Parliament. Now, more than seven years later, the self-styled Gandhian from Ralegan Siddhi village in Maharashtra is threatening another stir. This will be launched in Delhi on March 23 with pretty much the same demand—set up a Lokpal.

Anna’s threat coincides with the centre informing the Supreme Court earlier this month that it is in the process of appointing the anti-corruption watchdog but that it will first need to find an “eminent jurist” who can join the Lokpal selection committee. The committee, according to the Lokpal and Lokayukta Act 2013, must comprise the prime minister, the chief justice of India, Lok Sabha Speaker, Leader of the Opposition (LoP) in the Lok Sabha and an eminent jurist.

The political landscape of the country has changed drastically since Anna’s first agitation and so has his own stature. A brief recap of Hazare’s anti-corruption crusade and its political fallout is, thus, in order. Hazare’s comrades in the agitation of 2011 and the two years that followed till the enactment of the Lokpal Bill were a motley group of “civil society” members. A majority of them (Arvind Kejriwal, Kiran Bedi, Baba Ramdev, former Army chief General VK Singh, etc.) used the goodwill that the movement generated to launch their own political or quasi-political (as in the case of Ramdev) careers, and immensely successful ones at that.

The BJP, then the principal Opposition party, supported Hazare’s stir sensing that the public anger that he was triggering against the multiple-scam tainted UPA government could be channelised at the hustings to oust the “corrupt Congress”. The script played out spectacularly for the BJP in 2014.

If the scams in the allocation of 2G spectrum and coal blocks and in the 2010 Commonwealth Games had painted UPA II as corrupt, Hazare’s hunger strikes over an effective anti-graft ombudsman convinced voters that it was time for a change of regime. The Congress’ efforts at bending over backwards to bring Hazare’s “civil society nominees” on board to draft and then enact the Lokpal Act too couldn’t revive the party’s dwindling fortunes.

If the scams in the allocation of 2G spectrum and coal blocks and in the 2010 Commonwealth Games had painted UPA II as corrupt, Hazare’s hunger strikes over an effective anti-graft ombudsman convinced voters that it was time for a change of regime. The Congress’ efforts at bending over backwards to bring Hazare’s “civil society nominees” on board to draft and then enact the Lokpal Act too couldn’t revive the party’s dwindling fortunes.

All that the BJP’s prime ministerial candidate in the 2014 general elections—Narendra Modi—had to do was to ensure that the anger against the Congress continued to boil. And with remarkable proficiency, he promised the electorate a government which would not tolerate corruption.

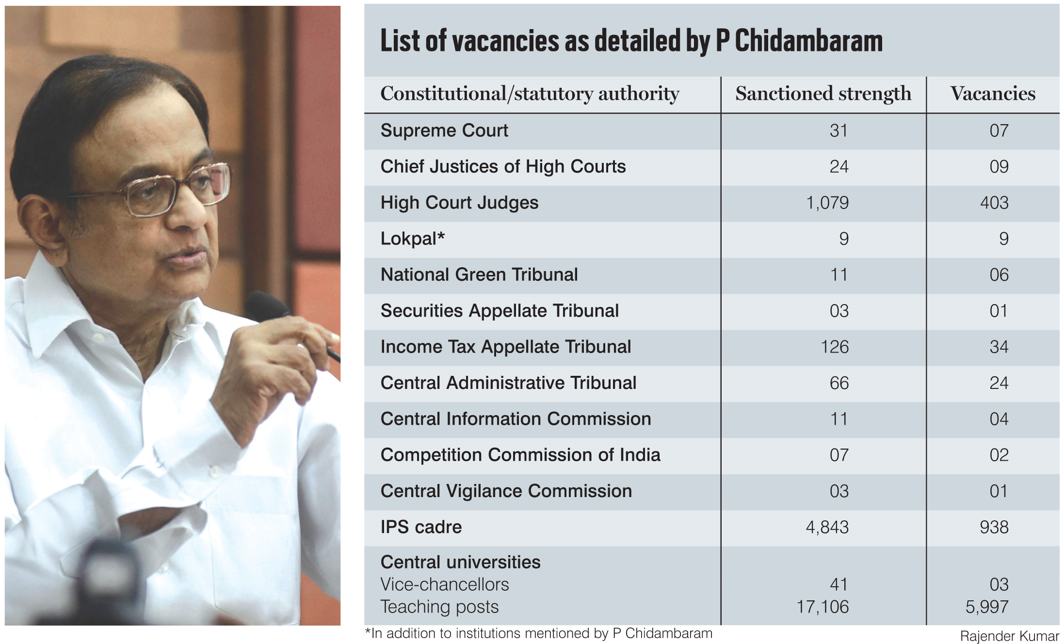

It’s been four years since Modi romped to power with a brute majority, promising the voters “naa khaunga, naa khane doonga”. In his weekly column—Across the Aisle—in The Indian Express, former finance minister P Chidambaram wrote on March 4: “The most misused cliché about governance is ‘That country is governed best which is governed least’. The clichés have depreciated so much that their value, in contemporary governance, is close to zero.” The column, a scathing critique of Modi’s promise of “minimum government, maximum governance”, highlighted the numerous vacancies in various constitutional and statutory bodies which the centre has been unwilling or unable to fill up.

Chidambaram’s article coincided with two events, one personal and the other with a potential for political leverage. On the personal front, it was the arrest of his son, Karti, in an alleged case of bribery during the UPA regime when Chidambaram was the finance minister. The other event was the Supreme Court’s reprimand to the centre on the delay in appointment of a Lokpal.

The Lokpal, as of now, is a ghost organisation existing only on paper. The government has presented two arguments for the delay in appointing a Lokpal. First, it says that an amendment to the Act, moved in 2016, to change the criteria for constituting the Lokpal selection committee was pending Parliament’s approval. This is, at best, a half-truth, if not a blatant lie, because the amendment doesn’t talk about changing the constitution of the selection committee at all and so its pendency for parliamentary approval does not arise. Yes, it is a fact that the single largest 0pposition party—the Congress—had failed to secure 10 percent of the Lower House’s strength in the 2014 elections and couldn’t be called the Leader of the Opposition (LoP). And yes, it is a fact that this thereby created a scenario wherein the Lokpal selection panel cannot be constituted as per the conditions laid out in the Act. The Opposition has been demanding that the Act be amended to replace the term LoP to leader of the single largest opposition party.

The second argument made by the centre’s department of personnel and training through an affidavit filed in the Supreme Court is that the selection panel presently doesn’t have an eminent jurist among its members and that the search for one is on. The last eminent jurist on the selection committee was senior advocate PP Rao, who passed away in September last year. The centre has, since Rao’s demise, been unable to find a worthy legal luminary who could join the Lokpal selection committee.

In January this year, the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information (NCPRI) had written a detailed letter to Modi, stating that the delay in the appointment of a Lokpal “has created a strong perception that your government does not wish to put in place an effective anti-corruption institutional framework”. Regarding the absence of an LoP, which is a hurdle for appointment of a Lokpal, the NCPRI letter stated: “In the absence of a recognised LoP, to operationalise the LL Act, a simple amendment was required to the law to provide that in the absence of a recognised leader of opposition, the leader of the single largest party/group in opposition in the Lok Sabha will be included in the selection panel.”

The government had informed the Supreme Court in February that a meeting of the Lokpal selection committee had been convened on March 1. Did the government not know then that its selection committee doesn’t have all the members mandated under the Act? After its submission to the apex court, the centre had requested Mallikarjun Kharge, leader of the Congress in the Lok Sabha, to attend the selection committee meeting as a “special invitee”, an offer that Kharge rejected.

NCPRI member Anjali Bhardwaj feels that the centre is misleading the country and even the Supreme Court on the Lokpal appointment issue. She told India Legal: “If the government is claiming that it wants to follow the Lokpal Act when it comes to convening a meeting of the Lokpal selection committee, then how is it calling Kharge as a special invitee when the Act has no such provision? The only option would have been to either appoint Kharge as LoP or to have changed the law so that the leader of the single largest party would sit in the selection committee. In the absence of such an amendment, if the government calls Kharge a special invitee, then where is the law to support it?”

The objective to have the LoP in the Lokpal selection panel was to ensure that the government appointed a Lokpal through broad political consensus and not nepotism. Bhardwaj wonders whether a special invitee to the selection committee would have the same powers as the LoP in the absence of a specific law? “If the centre decides to make a tainted individual the Lokpal, then would Kharge be able to oppose the candidature and ask for vigilance re-ports compiled by various agencies against this person? Will he have any real powers? The centre has not spelt out any powers for the special invitee. Would he be able to cast a valid vote and will his dissent be binding on the panel? None of these issues have been addressed by the centre,” she told India Legal.

While Chidambaram’s column in The Indian Express steered clear of mentioning the Lokpal appointment issue, it highlighted the larger issue of headless organisations or statutory authorities not being appointed by the centre. “Is this the minimum government that was promised by the BJP in the run-up to the parliamentary elections in 2014? The more important follow-up questions are ‘Who benefits by keeping posts vacant in crucial regulators and authorities?’ and ‘Who benefits from fewer RTI disclosures and fewer tax case judgments?’. The answer is obvious… If other institutions of a democracy are weakened, it gives greater power, in the real and practical sense, to the Executive,” Chidambaram wrote.

The Supreme Court, various High Courts, the Central Information Commission (CIC), the National Green Tribunal, various appellate tribunals, the Universities Grants Commission, and various central universities are currently functioning with varying numbers of vacancies against their sanctioned strength. (See box)

The CIC, the final authority on ordering the government to reveal details of Executive decisions sought by common citizens under the RTI Act, had remained headless for a long spell after the BJP came to power. While the Commission now has RK Mathur as its head, four of the ten information commissioners sanctioned for it are yet to be appointed.

Wajahat Habibullah, India’s first CIC told India Legal: “For many months after this government came to power, the central information commission was headless. One can give the Modi government a benefit of doubt for the initial phase, assuming that the government perhaps wanted to understand the role of the information commission and its members better before making the appointments… However, I must point out that the current government has failed to ensure that the basic requirement of filling existing vacancies, not of the chief information commissioner but of information commissioners and other staff, was fulfilled. As a result, once an officer retires, it takes the government a long time to fill the vacancy.”

The former CIC also conceded that the malaise of keeping democratic institutions inept in discharging their duties is not limited to just the CIC. “It is a fact that the government is not taking the right steps to strengthen democratic and constitutional institutions. This is visible not just by the vacancies in the Information Commission but a host of other institutions like various courts, the Lokpal, etc. It is the government’s responsibility to sustain institutions. Its failure to do so makes the prime minister’s attractive poll slogan of ‘minimum government, maximum governance’ look utterly hollow,” Habibullah said.

Former information commissioner MM Ansari was even more scathing. “Mr Arun Shourie, a BJP veteran and former Union minister, has rightly said that this is a government of two- and-a-half men. The fact is that these men who are running the State have no interest in sustaining constitutional institutions. A democracy thrives when its institutions are strengthened, but what we are seeing today is that the government is not interested in even ensuring that these institutions work as per their sanctioned strength. It appears that the government is willing to keep high offices vacant till such a time that they find candidates who are aligned with its ideology or those who are close to the powers-that-be,” Ansari said.

Ironically, the Supreme Court which is now seeking replies from the centre on the delay in appointment of a Lokpal, is itself battling the charge of not filling up vacancies for its judges. Of the 31 judges sanctioned, the Court is functioning with just 24. The Supreme Court collegium had unanimously recommended Uttarakhand High Court chief justice KM Joseph and senior advocate Indu Malhotra as judges in the top court. However, the government is yet to take a call on these appointments. Unconfirmed reports suggest that it has rejected the collegium’s recommendations. Worse, High Courts are functioning with 403 fewer judges than their collective sanctioned strength of 1,079.

In January, four senior judges of the Supreme Court (Justices J Chelameswar, Ranjan Gogoi, Madan B Lokur and Kurian Joseph) had, in an unprecedented press conference, highlighted the continuing delay by the centre in responding to the top court on the issue of Memorandum of Procedure for appointment of judges. The government has, till date, not addressed this issue.

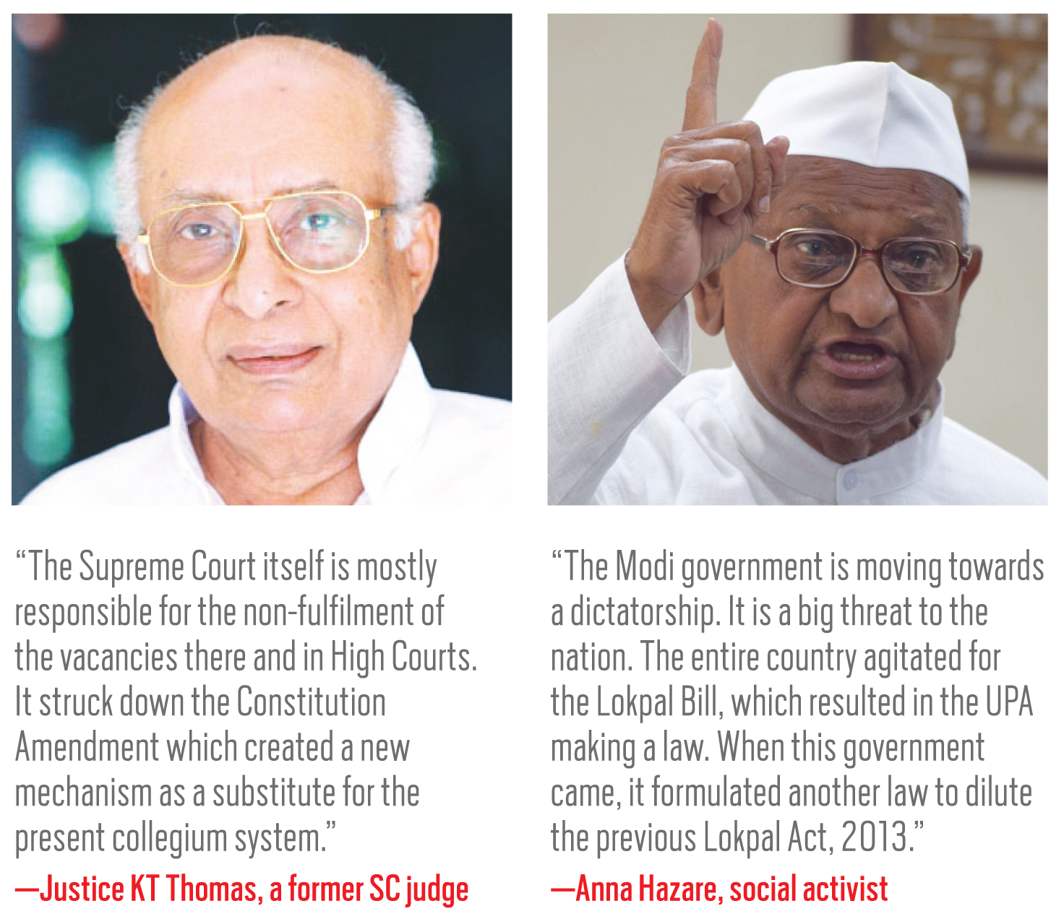

The vacancies in the top court, says Justice KT Thomas, a former Supreme Court judge, is a problem of its own making. “The Supreme Court itself is mostly responsible for the non-fulfilment of the vacancies there and in High Courts. It struck down the Constitution Amendment which created a new mechanism as a substitute for the present collegium system. The reasons advanced by the majority of the five-judge bench for annulling the Amendment are far from the range of acceptability. At the same time, the reasoning adopted by Justice Chelameswar in approving the same Amendment is very sound and valid,” Justice Thomas told India Legal.

So can the government be completely absolved of its responsibility in keeping the Supreme Court and High Courts functioning with a decreased strength in their benches? “If there is any delay on the part of the government in processing the recommendations already sent to it, it can be called upon by the Supreme Court on the judicial side to explain the reason,” Justice Thomas said.

Justice Thomas was also the man approached by the UPA government in January 2014 to head an eight-member panel tasked to shortlist candidates from some 400 applications to the Lokpal selection committee. The committee was to then appoint the Lokpal and his subordinates from this shortlist. But then, Justice Thomas declined the offer. A few months later, the UPA was voted out of power and the Modi government made no effort to reinitiate the Lokpal appointment process.

Justice Thomas says: “I declined to accept the post as I found that on the existing provisions in the Lokpal Act and the Rules, the government was not bound by the decisions of the search committee nor obliged to return the decision to the search committee for re-consideration. Instead, the Lokpal selection panel under the prime minister could make the appointments on its own. I felt that the labour exercised by the search committee headed by me would be futile. However, I expected the Parliament to make an amendment to the existing Act to correct the system of Lokpal appointment. The way in which parliamentary proceedings are being disrupted every day even on very important questions, I do not expect the amendment to the Lokpal Act to be made expeditiously. I do not know who can be blamed for this delay.”

With Hazare on protest mode again and highlighting the same issues that once endeared him so much to the BJP that the Congress had termed him saffron hitman, will the Modi government be compelled to expedite the Lokpal appointment procedure?

The possibility of such an eventuality looks dim. Firstly, Hazare’s sheen has worn off. His threats no longer make national headlines. Even his estranged comrade-in-arms, Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, seems to have forgotten his anti-corruption fight and has failed to appoint a Lokayukta in Delhi. Hazare looks like a caricature of the larger-than-life status he had achieved during the UPA era. Unlike the bumbling and nervous Congress, the BJP seems unaffected by his threats and is unlikely to even engage with him.

On his part, Hazare is trying to bring his Lokpal agitation back into political and media consciousness. Sources say he might even get the support of disgruntled BJP leaders like Yashwant Sinha and Shatru-ghan Sinha and their recently launched Rashtra Manch. Hazare is also trying to diversify his protest by speaking about the problems faced by farmers—a pet peeve of the Rashtra Manch leaders.

Hazare said: “The agenda for our agitation will be appointment of a Lokpal and farmers’ issues. The Narendra Modi government is moving towards dictatorship. It is a big threat to the nation. The entire country had stood up and agitated for the Lokpal Bill, which resulted in the UPA government making a law.

“When this government came, it was believed that it would help pass the bill. Instead, it formulated another law to dilute the previous Lokpal and the Lokayuktas Act, 2013 by removing the provision that required government officials to disclose the property held by their spouse. They are giving full-page advertisements about a corruption-free India but don’t want to appoint an anti-corruption watchdog.”

Evidently, Hazare is disenchanted with the BJP. But does it matter to Narendra Modi? There’s another year to go before the 2019 general elections. Despite the taint of corruption seeping into the Modi government with dubious industrialists fleeing to foreign countries, the latest being Nirav Modi, the BJP seems determined to not let graft become a rallying issue. The saffron party’s perception management through a media that’s ever willing to play ball, is likely to drown Hazare’s roars.

To recount Chidambaram’s observation: “Minimum government is intended to acquire maximum control, liberal democracy be damned and damaged.” That’s the new normal.