This emergency measure is meant to tackle urgent problems when Parliament is not in session but governments have often misused this constitutionally granted right in order to bypass legislative scrutiny

~By Puneet Nicholas Yadav

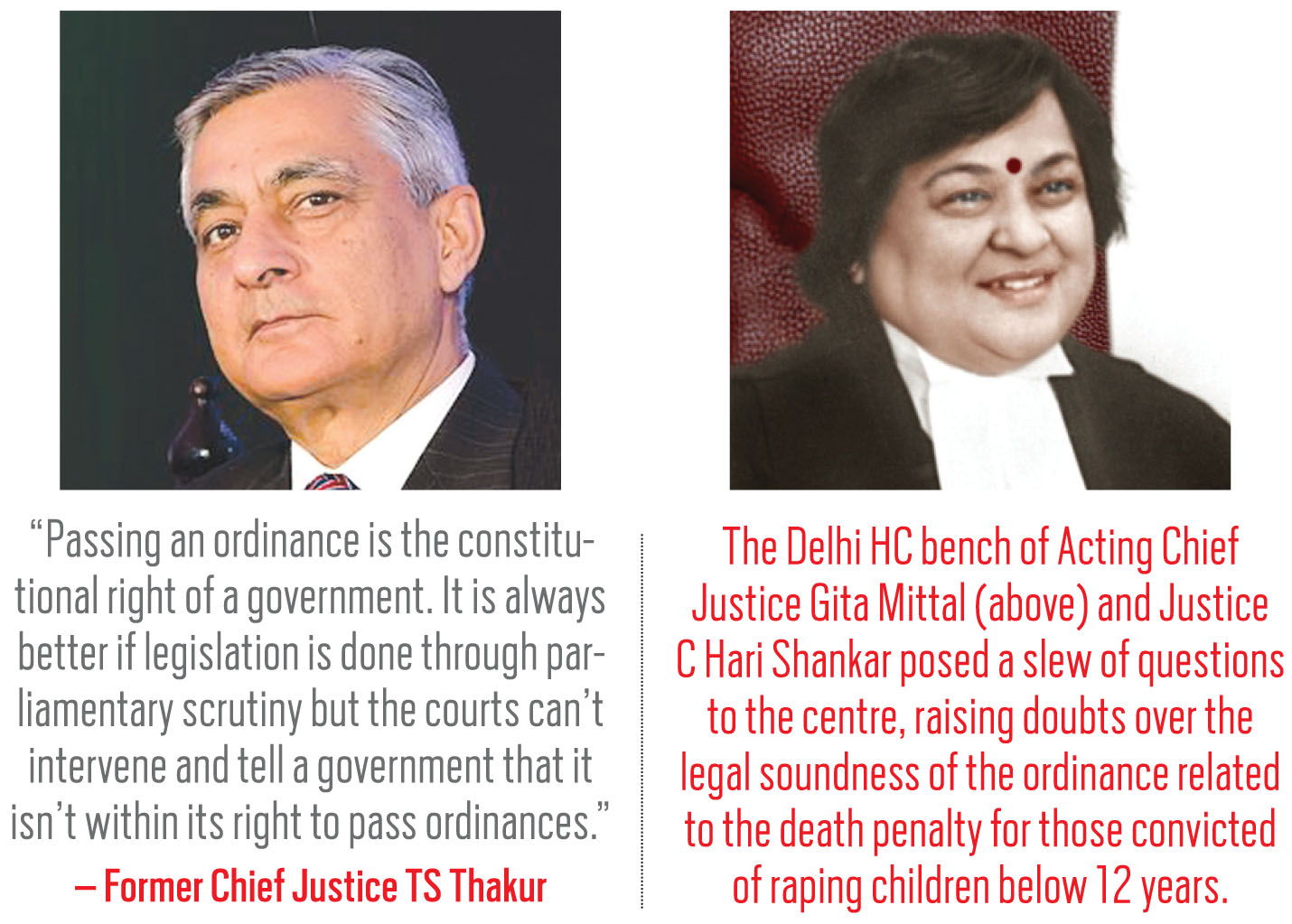

On April 21, the Union cabinet headed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi passed the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2018 which allows courts to award the death penalty to those convicted of raping children below 12 years of age. The ordinance was promulgated by President Ram Nath Kovind a day later but was promptly challenged in the Delhi High Court which asked the centre whether it had carried out any scientific assessment before arriving at the conclusion that the death penalty would act as a deterrent against rape. The Delhi High Court bench of Acting Chief Justice Gita Mittal and Justice C Hari Shankar posed a slew of other questions to the centre, raising doubts over the legal soundness of the ordinance, before asking: “Have you been to the root cause of the crime, or is it (the ordinance) the effect of the public outcry?”

The public outcry the bench was referring to was over the rape and murder of an eight-year-old shepherd girl in Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, and the rape of another minor in Uttar Pradesh’s Unnao district, in which the accused is a BJP legislator. Adding to the horror of the Unnao case was the fact that the father of the rape survivor died in police custody after he was reportedly beaten by cops and the brother of the accused BJP MLA, Kuldeep Singh Sengar, and his henchmen.

The Kathua and Unnao rapes had triggered a severe political backlash against the Modi-led government at the centre, the Yogi Adityanath government in Uttar Pradesh and the BJP in J&K, where the party is a partner in the ruling Mehbooba Mufti-led coalition and where some of its legislators and ministers had publicly supported the rapists. Possibly sensing that a reprisal of public anger, last witnessed in the aftermath of the Nirbhaya gangrape, would brand the BJP as a party that not only compromises on women’s safety but also supports those perpetrating these crimes, the centre hastily drafted the ordinance. It was passed at a special cabinet meeting convened on a Saturday (the cabinet normally meets on Tuesdays).

What fervour!

Some ordinances passed by the Modi government in the past four years:

- Indian Medical Council (Amendment) Ordinance, 2016

- Dentists (Amendment) Ordinance, 2016

- Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation), Second Ordinance, 2016

- Uttarakhand Appropriation (Vote on Account) Ordinance, 2016

- Enemy Property (Amendment and Validation) Ordinance, 2016

- Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Ordinance, 2015

- Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Second Ordinance, 2015

- Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Second Ordinance, 2014

- Insurance Laws (Amendment) Ordinance, 2014

- Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (Amendment) Ordinance, 2014

- Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2018

- Fugitive Economic Offenders Ordinance, 2018

The flaws and obvious lack of thought and study that went into drafting the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, 2018, as evident in the Delhi High Court’s stern posers to the centre, have been extensively written about. But they are also the result of another malaise that seems to strike most governments—that of misusing their right of promulgating ordinances.

An ordinance is an emergency measure, provided under Article 123 of the Constitution, to tackle urgent problems when Parliament is not in session. If the parliament is in session, legislation must be brought in and approved by it and then subsequently assented to by the president. An ordinance, on the contrary, is issued by the government, assented to by the president and passed within six months and six weeks as a law in the normal course by Parliament. However, if for some reason, the ordinance can’t be passed by Parliament within this mandated period (if Parliament doesn’t function due to a logjam), the ordinance would automatically expire. The government then has the option of requesting the president to re-promulgate it.

Vivek Tankha, senior advocate in the Supreme Court and a Congress MP, believes that while “a government cannot be questioned on its right to bring in an ordinance since this is guaranteed by the Constitution, Article 123 should be invoked only in absolutely urgent situations”. He told India Legal: “The ordinance route, particularly for matters that affect the society, is less desirable than the normal process of scrutinising a bill by Parliament and its standing committees. What we are seeing today is an abuse of Article 123 for what can be called a self-serving agenda, wherein the government brings in an ordinance to either counter political challenges or make a statement about an issue it has failed to address through governance.”

In the past four years, over 35 ordinances have been promulgated. Nine of these were issued within the first eight months of Modi becoming the PM. The Modi government began its innings with a recommendation for two ordinances at the very first meeting of the Union cabinet. Within a fortnight of taking charge in May 2014, the cabinet recommended an ordinance to amend the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act to facilitate the appointment of ex-TRAI chief Nripendra Mishra as principal secretary to the prime minister (an ordinance that was purely meant to address the whims of the premier and was of no consequence for the citizens at large), and the other to amend the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act for transfer of a cluster of villages for the Polavaram project.

There is no doubt that the Modi government did bring in some ordinances that were meant to smoothen legal hurdles caused by existing laws. These included the Enemy Property (Amend-ment and Validation) Ordinance, 2016; Indian Medical Council (Amendment) Ordinance, 2016; Citizenship (Amend-ment) Ordinance, 2015; Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Ordinance, 2014, etc. However, a number of other ordinances were largely political tools, either aimed at bolstering the image of the government and its leader or endearing the new regime to corporates and industrialists who had visibly ditched the Congress during the 2014 general election in favour of the pro-business BJP.

While the Modi government did steer into choppy waters when it brought the ordinance to facilitate Mishra’s appointment as Modi’s principal secretary, the regime faced the first full brunt of the Opposition’s tirade over its “Ordinance Raj” when the cabinet approved the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Ordinance, 2014.

The ordinance was meant to severely dilute the strident provisions of the land acquisition law passed by the UPA government which gave farmers, small land holders and the common man greater rights to compensation in the event of their land being acquired by the government or private players. The government’s unabashed arrogance in attempting to turn pro-poor legislation into pro-business, and that too without due deliberations in Parliament, gave the Opposition the ammunition it needed to attack the seemingly infallible Modi and saw then Congress Vice-president Rahul Gandhi coin his “suit-boot ki sarkar” jibe for the BJP regime.

Given his party’s brute strength in the Lok Sabha and continuing victory march at the hustings in elections to the Maharashtra, Haryana and several other provincial legislatures, Modi had the misplaced notion that he could storm ahead with the land acquisition ordinance. Despite protests by the Opposition, the ordinance was not tabled in Parliament sessions convened after it was promulgated but was re-promulgated twice in 2015 before Modi was forced to finally eat humble pie and withdraw it.

In the same boat

Total number of ordinances promulgated by the previous regimes between 1952 and December 2014: 679

- Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (1952-1964): 70 ordinances

- Indira Gandhi (1971-1977): 77

- Rajiv Gandhi (1985-1989): 35

- PV Narasimha Rao (1991-1996): 77

- United Front government (1996-98): 77

- Atal Bihari Vajpayee (1998-2004): 58

- Dr Manmohan Singh (2004-2014): 61

Source: Lok Sabha publication, Presidential Ordinances 1950-2014

A little over two years into power and weeks after Modi decided to stun the country with his demonetisation move, his cabinet passed another ordinance—the Specified Bank Notes Cessation of Liabilities Ordinance, 2016. With this ordinance, the Modi government created another first of sorts in India’s legislative history. A bulk of the provisions of this demonetisation ordinance were meant to kick in at a future date—after March 31, 2017, when the RBI’s 19 exchange counters for demonetised currency notes across the country were to be closed. Ordinances are meant to take immediate effect as the constitutional rationale behind them is to address an urgent situation—an ordinance which is post-dated (as the demonetisation ordinance certainly was)—is an oxymoron.

Over the past fortnight, the government has once again gone into ordinance overdrive, passing two of them with both equally flawed legally. Aside from the Criminal Law (Amendment) Ordinance, the cabinet has also passed the Fugitive Economic Offenders Ordinance (analysed in clinical detail in the May 7 edition of India Legal).

While the Delhi High Court has, rightly, pulled up the centre for its hasty anti-rape ordinance, former Chief Justice of India Justice TS Thakur believes that when it comes to judicial scrutiny of ordinances or even legislation passed by Parliament, “the scope for courts to interfere is very little”. “The courts can scrutinise whether an ordinance or legislation violates the fundamental rights of a citizen or contravenes any other Articles of the Constitution and if they find this to be the case, then they can strike it down. Passing an ordinance is the constitutional right of a government. Of course, it is always better if legislation is done through parliamentary scrutiny but the courts can’t intervene and tell a government that it isn’t within its right to pass ordinances. If the ordinance is not brought before Parliament within the constitutionally mandated period and the government simply re-promulgates it, then a challenge in courts is possible,” Justice Thakur told India Legal.

In January 2017, a constitution bench headed by Justice Thakur (he was then the CJI) had passed a verdict that famously held that ordinances are not immune from judicial scrutiny when the “power has been exercised to secure an oblique purpose”. The 5-2 majority verdict, which came on a bunch of petitions that challenged an astronomical number of ordinances passed by the Bihar government between 1989 and 1991, had also slammed repeated re-promulgation of ordinances. Though Chief Justice Thakur and Justice Madan B Lokur constituted the minority opinion (the majority verdict was authored by Justice DY Chandrachud), the judgment laid down clear directives for the government on re-promulgation of an ordinance. Ruling that re-promulgation of an ordinance was a “fraud on the constitution”, the verdict had held: “Re-promulgation defeats the constitutional scheme under which a limited power to frame ordinances has been conferred on the President and the Governors. The danger of re-promulgation lies in the threat which it poses to the sovereignty of Parliament and the state legislatures which have been constituted as primary law givers under the Constitution.”

The apex court’s verdict against re-promulgation of ordinances also highlighted that the ruling through this constitutionally-granted tool was a malaise as deep-rooted in the states as it is at the centre. Earlier this year, the Vasundhara Raje-led BJP government in Rajasthan had made national headlines for passing a controversial ordinance. This sought to gag the media by prohibiting it from reporting on corruption cases filed against bureaucrats till such time sanction was granted to prosecute an officer. Following protests, Raje was forced to withdraw the ordinance.

By virtue of being in power now, the Modi government is obviously in trouble for its ordinance run. However, it seems to be following, perhaps with greater brazenness, a practice that its predecessors had turned into a new normal.

The Dr Manmohan Singh-led government during UPA-I (2004-09) had issued 36 ordinances. UPA-II (2009-14), with better numbers in Parliament, had issued 25. A total of 61 ordinances in 10 years or an average of six each year! The memory of Gandhi arriving unannounced at a media interaction in the Press Club of India on New Delhi’s Raisina Road, and tearing to bits a copy of a controversial ordinance passed by his party’s government days earlier to shield convicted politicians from losing their seats in Parliament (or state assemblies), is fresh in public memory.

A Lok Sabha publication titled Presidential Ordinances 1950-2014 issued in early 2015 shows that after the Constitution came into force and till December 2014, the president has promulgated 679 ordinances. Of these, 456 were issued in about 50 years of rule and by six prime ministers of the Congress. India’s first prime minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, had cleared 70 ordinances from 1952 to 1964. Indira Gandhi issued 77 ordinances during 1971-77, at the rate of almost three ordinances every two months. The Rajiv Gandhi government issued 35 ordinances in five years from 1985-89 while the minority Congress government of PV Narasimha Rao issued 77 during its five-year term. The left-backed United Front government which was supported by the Congress from the outside passed only 61 Bills during its 1996-98 term under two prime ministers, HD Deve Gowda and IK Gujral, but issued a record 77 ordinances at a strike rate of more than three per month. The first NDA government, headed by the BJP’s Atal Bihari Vajpayee issued 58 ordinances between 1998 and 2004, at a rate of nine a year.

While the BJP may argue that Modi’s government is neither breaking from tradition nor doing something unconstitutional, the fact is that ordinances must remain an exception. The framers of the Constitution did not envisage this right for governments so they could address their self-serving agenda. Modi would do well to bear this in mind.