India is poised to enter the international alternative dispute resolution arena in a big way. But to seize the opportunity, Indian law firms must gain acceptance in the country and abroad for their competence and reliability

~By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

Mumbai and Gurugram (the old Gurgaon) seem to be vying with each other to make India the hub of international arbitration. The Mumbai Centre for International Arbitration (MCAI) was set up in October 2016, and on January 19, 2017, Gurugram District and Sessions Judge Harnam Singh Thakur disclosed that the Punjab and Haryana High Court has passed a resolution and a proposal was sent to the Haryana government for setting up an international arbitration centre in Guru-gram, which houses a bunch of Fortune 500 companies.

The race has just begun, and there is excitement in the air about the possibilities of India tapping the talents of its legal community of former judges and lawyers to provide arbitration services in a free market global economy. Private companies from different countries are already entering into partnerships through complex commercial agreements. Differences and disputes are bound to arise and there is a need for a legitimate institutional framework to resolve the disagreements, which at the same time avoids the legal labyrinths of litigation.

To the question whether India has a long way to go before it can make its presence felt globally, senior Supreme Court lawyer Gaurab Banerjee says: “Delhi alone deals with 200 arbitration cases in a year, which is what Singapore does. Singapore knows how to market itself.” Right now, London is the leading arbitration centre, followed by Singapore and Hong Kong.

There are others who feel that India is still to acquire the expertise as well as the infrastructural facilities to attract international arbitration cases.

D Sengupta, joint registrar of the 1965-established Indian Council of Arbitration (ICA) says: “There is a need to change the mindset. The Indian arbitration scene is still dominated by retired judges and lawyers. Arbitration is meant to move away from the rigidities of the legal system.”

Organisations like MCIA and ICA want disputants to approach arbitral institutions which will provide the arbitrators from a panel of retired judges, lawyers, business persons and experts

He cites the example of a dispute between a Mumbai-based construction company and a public sector unit in Kolkata, where the arbitration went on for 40 hearings. It was only when a construction engineer was named as an arbitrator that the matter was resolved in the next two hearings.

He also says that lawyers in India are not dedicated to arbitration issues, and that they take up the assignment as something additional to the regular court cases they handle. This is why many lawyers want the arbitration hearings to be after 4 pm. Justice Rekha Sharma, who has taken up arbitration assignments after her retirement from the Delhi High Court, concurs. She says that this impedes the pace of hearings.

Prominent arbitration awards involving Indian companies

- In June 2016, the London Court of International Arbitration awarded damages of $1.1 billion to DoCoMo because the Tatas could not find buyers for the 26.5 percent stake when the Japanese company wanted to exit. RBI had objected to the payment, but the Delhi High Court overruled the objection in an order last week. But the Court asked Tata Sons to seek the clearance of Competition Commission of India.

- Singapore’s Arbitration Tribunal had imposed a penalty of Rs 2,562 crore on Ranbaxy in the dispute with Japanese pharma major, Daiichi Sankyo. The Japanese company has moved the Delhi High Court for enforcement of the arbitration award. Ranbaxy is arguing that Indian law does not provide for “consequential changes” and also that Daiichi Sankyo had since made monetary gains by selling its Ranbaxy shares to Sun Pharma.

- The London Court of International Arbitration had asked construction major Unitech to pay $300 million to Cruz City 1 because the company and its subsidiary refused to buy shares of Mauritius-based Cruz City 1’s Cyprus-based partner Kerrush according to an agreement between them. Cruz City approached Delhi High Court for enforcement of the arbitration award. Unitech is arguing that paying an assured return to a foreign partner violates the Foreign Exchange Management Act. The Court rejected Unitech’s contention and said the London arbitration tribunal’s award did not go against public policy in India.

- The Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague has ruled against India and in favour of Devas Multimedia, which had entered into an agreement with Antrix Corporation, the commercial arm of ISRO. A 2011 draft audit report found irregularities in the deal between Antrix Corporation and Devas, which involved Antrix leasing 70 Mhz of S-Band to Devas for 12 years, in return for upfront payment of $30 million. The deal was scrapped because of political furore over the deal.

Banerjee agrees with the need to move away from retired judges being appointed arbitrators, but he is optimistic that change is bound to happen as the number of arbitration cases rise, and there are not enough retired judges to man the arbitration tribunals. He thinks then the lawyers will take over as arbitrators.

Neeti Sachdeva, registrar and secretary general of the MCAI, says that her institution has a training programme for young lawyers in arbitration and it would soon create a pool of experts who would ease the working of the system. She also emphasises the need to move to institutional arbitration and away from ad hoc arbitration. The difference is this. Most commercial agreements nowadays have an arbitration clause. When the partners disagree, they approach a court citing the arbitration clause, and the court appoints an arbitrator. In some agreements, each of the partners names its own arbitrator, and the two arbitrators then choose a third one, who will preside over the arbitration.

Arbitration is a general norm in commercial disputes, but the norms and institutions are yet to establish themselves and command universal consent.

But organisations like MCIA and ICA want disputants to approach arbitral institutions which will provide the arbitrators from a panel of retired judges, lawyers, business persons and experts, and also provide the physical infrastructure to hold the proceedings of arbitration. The secretarial staff will provide the support in preparing the arbitration verdicts and other paper work.

Of course, there will be a charge for services and there is a tariff list. It is a lucrative option as well. Though arbitration institutions are not-for-profit organisations, they provide services with the promise of concluding matters expeditiously and efficiently, and they collect the user-charges as it were.

There are arbitration institutions and traditions in India which have evolved slowly in the last half-century and so. For example, the ICA was established in 1965 after a Government of India team toured other countries and prepared a report and recommended the setting up of an arbitration centre.

The ICA was supported by the government but it was recognised that to be credible it had to remain at arm’s length from the government. The ICA was given space by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), and the support of FICCI has proved invaluable, says Sengupta. From 1997 onwards, the ICA has become self-sufficient and it does not receive financial assistance from the government.

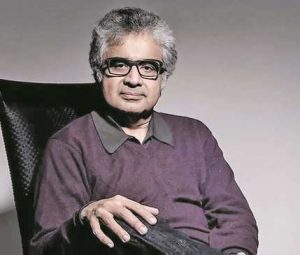

Harish Salve, a chartered accountant who turned to law, is actively engaged in arbitration cases in London and Singapore. He is one of the few senior Supreme Court lawyers who is an arbitrator at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. He also volunteers to be an arbitrator in emergency cases

Harish Salve, a chartered accountant who turned to law, is actively engaged in arbitration cases in London and Singapore. He is one of the few senior Supreme Court lawyers who is an arbitrator at the Singapore International Arbitration Centre. He also volunteers to be an arbitrator in emergency cases

Is the institutional framework for arbitration in India in place?

In theory there is an institutional framework. But unlike Maxwell Chambers (in Singapore) or the IDRC in London, there is no facility in which arbitration hearings can be held. Five star hotels are not convenient venues. There are no facilities for “live notes” (live transcription of oral hearings) which is a given in all international arbitrations.

What holds back India from emerging an international arbitration hub?

Lawyers do not take arbitrations seriously. Arbitrations go on endlessly— adjournments are asked for and granted for the asking. If the arbitrators are strict, the courts intervene: Hardly a conducive atmosphere for arbitrations. I do not see—in the short-term—India becoming a relevant centre for arbitrations.

An interesting view of the Indian arbitration market is to be found in the decision of the London Court of Inter-national Arbitration (LCIA), which shut off its special offering of LCIA India rules in June 2016. The LCIA India rules were formulated in 2009 with the hope of serving the Indian clientele and their specific needs.

The statement said: “…after six years, it has become apparent that Indian parties are equally content to continue using the LCIA Rules and there are insufficient adopters of LCIA India clauses to justify a continuation of the LCIA India Rules as a separate offering. This situation is not expected to change in the near term. Accordingly, the LCIA has concluded that the best way for it to serve the Indian market is to do so from London, as it has traditionally done.”

This means that Indian companies are content to use international rules and norms for arbitration as set out by the LCIA. This would imply that Indian arbitral institutions will have to provide global standards for domestic as well as foreign companies in India to attract those seeking settlements of commercial disputes.

The Arbitration and Conciliation Amendment Act of 2016 has now mandated through Section 29A that arbitration should happen in a year’s time, and that it could be further extended by six months. Senior Supreme Court lawyer Gautam Mukherjee thought that this was good and that it will help speed up the proceedings.

Two persons disagreed. Justice Rekha Sharma felt that it was too short a time in which to settle a matter, and felt that the initial period should be 18 months, and the extension could be for another six months.

Justice AP Shah, former chairman of the Law Commission, in his speech at the Ninth International Arbitration Conference at the Nani Palkhivala Arbitration Centre in Mumbai on February 18, 2017, said: “Section 29A has had some positive impact – because of the stipulated timelines, arbitrations are moving quickly. Arbitrations must move faster, but the principle that ‘finality is good but justice is better’ is also relevant. In complex cases, a tribunal will need substantially more time than provided to conclude the matter.” It was during his tenure as chairman that the 246th Law Commission Report recommended changes in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.

Justice Mukul Mudgal also feels that Section 29A is unrealistic. He says that the one-year timeline works if the period of preparation and submissions is excluded. One year should be the time allotted for actual pleadings. He says the Delhi Arbitration Tribunal follows this norm and it works well.

Though international commercial arbitration is the dominant note in discussions about arbitration and arbitral institutions, arbitration seems to be gaining in the country away from the arc-lights as it were. Justice Shyam Kishore Sharma, who is now the Lokayukta in Bihar, was heading the Bihar Arbitral Tribunal, which was set up eight years ago. He was the second head of the Tribunal. He expressed great satisfaction with the number of disputes he had been able to resolve as an arbitrator, which usually involved construction companies. He said that he was able to solve 300 to 350 cases in a span of nine months to a year.

He felt that the Indian arbitration system is satisfactory, but he was not complacent. He said that there is need for evolving to meet global standards.

Arbitration is a general norm in commercial disputes, but the norms and institutions are yet to establish themselves and command universal consent. In many cases, one of the disputing parties, unhappy with the arbitration award comes back to the courts. The courts have refused to intervene because of the arbitration clauses that were written into the agreements. In a recent case been the Union of India and Reliance Industries, the Union of India, unhappy with the arbitration tribunal in London, appealed against it in Indian courts. Paying attention to the arbitration clauses in the agreement between the parties, the Supreme Court Bench comprising Justices AK Sikri and RF Nariman said in the judgment delivered on September 22, 2015, that if the parties had chosen London and the English Arbitration Law, then it cannot be challenged by invoking the Arbitration and Conciliation Act of 1996.

There is ample case law in the Supreme Court that has emerged over the last decade and more with regard to arbitration matters, and it points out to issues of jurisdiction. The tendency to challenge arbitration awards in the courts will have to lessen if arbitration is to become the norm.

The other important issue that comes up is whether India needs competing arbitration institutions given the large size of the country’s economy. Sachdeva of MCIA is of the firm view that not competition, but credibility, is the answer. She refers to LCIA, which commands the respect of disputants beyond British borders. Sengupta of ICA also emphasises the issue of credibility but he thinks that competition among arbitration institutions need not be a bad thing.

Mumbai and Gurugram can be arbitration hubs but they need not necessarily compete with each other. What will be of greater importance is to gain acceptance in the country and abroad for its competency and reliability.