By Mahmood Farooqui

One of the most celebrated and enduringly popular works in Urdu, billed as a qissa or Dastan, is Qissae Chahar Darwesh, or the Tale of the Four Dervishes. Ascribed sometimes to Amir Khusrau, it was rewritten two hundred years ago by Mir Amman Dehlavi at Fort William College, Calcutta to enable the Angrez Sahiban to learn Urdu. Like that other timeless classic Alf Laila, or the Thousand and One Nights aka Arabian Nights, this one too is full of adventures, mysterious occurrences and supernatural beings. But it begins on a very modern note. A world weary Prince finds four Dervishes in a desolate spot. They start sharing stories. We learn that all four of them, and our Prince, led very exciting lives but were all eventually led to their ruin by a combination of their personalities and circumstances. It is thus also a saga of ruined lives. It is a huge tribute to Tarun Tejpal’s qissagoi or storytelling skills that he has written a very modern epic of ruined lives which can simultaneously seem pre-modern and timeless. The Line of Mercy is set in an unnamed world of iron bars, but it is not a prison novel, or not only a prison novel. It is a novel about politics, law, society, cops, media and about the million mutinies that everyday rage around us. It is a novel about lovers, alcoholics, small time fascists, clowns and jugglers, suspicious husbands, boy lovers, broken lives, seconds of madness, and the brotherhood of a world where bare youth makes power and wealth bend to its dictates. It is about fate, and justice, and the extraordinary will, and wilfulness, of ordinary people. It is about philosophical ideas and pathetic weaknesses, about sublime emotions and bathetic consequences, about how some grow sad and some grow mad, but above all it is an audacious ode to the human spirit. It depicts, in Dickensian fashion, the vast underbelly of subaltern India, which sometimes traps the rich and powerful too.

The story begins with Sambhav Kumar, long christened Asambhav for the impossibility of his rectitude, and the goodness of his bearing, who nevertheless metes out the first and mandatory corporeal punishment, and ritual humiliation, to all newcomers to the iron realm. This handsome, strong, dutiful, and literature loving high caste son of an army man from Benaras finds his life unravelling when he falls in love with a lower caste girl Aranya. The tribulations and undulations of this epic and cinematic love story, propelled by Hindi film songs, forms the spine of the book where tradition, destiny and human resolve pit themselves against each other before everything comes apart. But eventually the very be aib Asambhav, who possesses a character without any vices, finds peace as his efficiency and integrity make him the darling of both the inmates and the khakis who run the realm. He also finds fulfilment as his paramour is at last near him, despite the walls (Mathilukal in Vaikom Mohammed Bashir’s eponymous and immortal story about prison love) that separate them.

At the other end of the spectrum is Dr Desai, a highly successful self-made businessman who finds himself the object of crazy media attention when four kids in his nursing home die because of spurious drugs. As the media pillories him he comes to realise that what had seemed like a pantomime trial, ‘all sweetly choreographed not just for the satisfaction of the keening masses but also to keep in place the propriety of things,’ was actually a suction machine which was irresistibly sucking his life away. With tremendous skill Tejpal unfolds the foretold chronicle of a man who is going to go down, bit by slippery bit. As his lawyer observes, like all condemned men Desai makes cosmic deals, as the prospect of the iron bars fills ‘them with piety and compassion and mercy and suchlike sweet milks. For a time they became good men. And that is all one can ever hope for—that briefly men will be good.’

Still Desai hopes, banking on ‘good sense and fair play and his essential guiltlessness,’ and like all men being led to the guillotine places his last hope when he appears before a judge—

“Desai tried to look his contrite best in the hope of some grace. Surely she could see he was a good man who was honourable to his wife and children and parents and friends. A good man caught in an unsavoury situation not of his making. She did not even look at him. In less than a minute she had dismissed the police plea for further custody and committed him to judicial remand.”

What happens with Desai is also the everyday fate of thousands upon thousands of undertrials who languish without ever so much as a glance from their judge. Desai, a rich man, a wip i.e. VIP, is both privileged and a target in the iron walls. Before he finds his equilibrium he must take his beatings, from men like Bichchoo and Peter the Fist who rule this realm:

“Out there in the unjust world Bichchoo—the son of a slum—would not have been allowed to cross the threshold of Dr Hagg’s house. Men like the entrepreneur had kicked his forefathers more brutally and continually for transgressions far less serious than murdering babies. Every hair of Bichchoo’s thrilled to a potency.”

Desai’s weak sphincter is unable to take physical beatings and hence his moniker Dr Hagg. But still Desai learns to live, and cope, as he finds his own place in the land without the Sun.

In delineating the backstories of people who populate this realm Tejpal presents to us a cross section of our country, a country in turmoil, caught in the vortex of limitless aspirations and limitless poverty. He tells the story of Bichchoo, a slum boy who detests the squalor of his home, and the wound of having an absentee father, and takes refuge in long tales and smokes. While his elder brother Sparkplug ploughs on with studies, sponsored by Bichchoo, and advocates keeping to the straight path, Bichchoo discovers that there are two roads to the world:

‘One ran through education and the other through guile…In their dance of justice the gods give as much potency to guile as to education. While education preens, it is guile that rules it with casual mastery.’

Bichchoo makes an unlikely friendship with a differently-abled boy, a relationship that reminds one of the cripple boy in Mario Vargas Llosa’s remarkable novel about the rebellion of the underdogs in The War of the End of the World. They become curious objects for a beautiful outsider family, building their beautiful mansion and a beautiful swimming pool and Bichchoo takes full advantage of his exoticism in their eyes. He also becomes friends with a local compounder who relates tales of the legendary Dr Schultz, whose fantastical exploits resemble a Marquezian lore as well as a medieval Dastan. Bichchoo scorns the world and even comes to share his lover with his friend. But how can he escape his circumstances? Poverty, alcohol and drugs transform him, momentarily, into a beast and he ends up murdering his lover, her husband and their two kids after his friend is fatally wounded. Bichchoo commits an act of desperate depravity and with extraordinary empathy, not unlike Dostoevsky, Tejpal humanises his story and lets us know that acts of depravity do not necessarily a depraved person make. The head of the iron realm nicknamed Singham well knows how arbitrary the whole process is when he reflects about the number of boys who were innocent, and “of the guilty how many were driven to error by the same men who then condemned them? Of those who condemned how many were guilty of the very things they condemned in others. Every day he felt his own innocence and the guilt of his wards was separated by nothing more than one mistake. One unwitting incident…”

There are others in that realm who have made their own circuitous and condemned journeys to degenerate culpability. There is Francis, forced by his employer Papa’s overflowing love into molesting his daughter, with disastrous results for all. There is the thin, unprepossessing Salvador, scion of an old Goan family who begins to suspect his beautiful wife, ‘Nadia the pear’ of infidelity from the very first night. The world of this tortured soul and his fantastical scheming has been drawn with exquisite beauty, reminiscent of something Marquez might have done here. The sufferings of the retrograde and the reprobate, ever the haunting ground of that great chronicler of human suffering Fyodor Dostoevsky, also come alive in these pages. The padekar who suspects his wife of fantasising about motorcycles, the plumber who desperately wants to love his wife but in another moment of alcohol produced rage ends up murdering her and her sister before he becomes terminally blind in the prison (hence his moniker Andha Kanoon), the lustful boy Bobo who ends up killing a dog and his elderly lover, are all drawn with empathy, without revulsion. The singular achievement of this novel is to get inside the mind of depravity and show it to be so so human, so normal.

But Tejpal’s novel is not only about crime and punishment, not only about a penitentiary and its wayward denizens. It is also a moving account of stunted lives, of ambition and aspiration. In an episode of startling realism he shows how Ajay, a first time offender, develops cold feet in his first attempt at kidnapping and wants to do right, but it is too late by then. There is a beautiful portrait of a circus acrobat Jogen Jabda and his failed footballer father, a life gone wrong just because the father’s bicycle rammed into a buffalo and he fractured his leg. Fascinated by the circus as a child, Jogen runs away from home and finally joins a circus. Jogen’s life in a circus—run by the enchantingly timeless Shabnam Bandookbaz—and his early training are described with panache. Jogen’s debut as a performer is a scintillating set piece and you soar with him and soak his exhilaration as he enjoys the show. It is a passage of incandescent beauty, as is the moment when, after sustained degradation inside the iron realm, one day Jogen earns applause and respect as he begins to juggle steel plates and cups. A performer’s dignity lies in performance and sometimes no confinement can impair that. It is to the novelist’s credit that if he had set this episode three hundred years ago it would have still rung true.

The Line of Mercy is a picaresque adventure, but it is also a portrait of India on the move. Aspiring fascists like Babu, who would never be imprisoned today, dream of an India free of Muslims, and of a king ‘with some brain and much bicep who would whip the clerks to move the files and build the roads and who would revert all Muslims to Hindus—which everyone was before they were seduced to become other things—or get rid of them altogether.’ It knows where the faultlines lie but also possesses the wisdom to know how easy, and tiresome, it is to outrage in India where ‘by evidence of caste and religious violence Indian civilisation ends every week.’ But it is also a meditative work which raises philosophical questions about life and about Art, and about why some lives are stunted and some not. It is also about the stories we tell ourselves of our lives, which really is the most important story.

“All men, even those who don’t kneel to the idea of God, believe their lives are a cinema script. They take their tribulations for narrative twists. They believe at the right moment events and people will come together to grant them their due. And by the conceit of Art they will never be denied their redemption. It is why Art always loses to life. Life cares nothing for solace or approval. Life likes accidents. Art hunts for coincidences. Life is happy to snub hope. Art is desperate to construct hope.”

As Jogen mediates on his life in the iron realm, he begins to think of the what-ifs of his life and is forced to arrive at a Tolstoyean vision of predetermination which comprises thousands of infinitesimal and invisible causes. No matter how “manically he chopped and stitched the footage of his life he could not find a narrative that could take out the distress without taking out the exhilaration too.” Tejpal’s novel is about fate, and about the deep hierarchies that dominate our society, which as the sociologist Louis Dumont in Homo Hierarchicus had advanced long ago, is the singular defining feature of Indian society. Inside the iron bars Desai would come to understand that the world is divided into the RightBorns and the WrongBorns:

The RightBorns are amazed when things go wrong

The WrongBorns are amazed when they go right

The RightBorns struggle with the idea of injustice

The WrongBorns struggle with the idea of justice

The RightBorns tend to feel outrage

The WrongBorns stick to feeling rage

The WrongBorns take their knocks as they come

The RightBorns kick and scream and demand cosmic redressal

As should be obvious by now, with its unforgettable characters and its perversely gripping stories, The Line of Mercy is a work of dazzling wisdom. As a novel about crime and punishment, it of course shows virtuoso familiarity with cops and criminals. But its greatest overarching concern is with justice, and its many shades. Tejpal delves with great insight into the mind of an upright judge and brings out assumptions that dominate the criminal justice system across the board. She distrusted “pure context—which was ever eager to exonerate. And she distrusted pure code-which was eager to punish. She was drawn to the idea of the deterrent and the corrective. As a good Judge she understands the difficult conditions under which cops work and therefore, the first thing she learnt was that ‘the police broke the law every day but without breaking it they would never be able to uphold it [because] a judge did not interpret the law. A judge ensured a lawful society.’” She knows that it is not important that people get justice. It is important that the people think there is the possibility of getting justice. But she also knows the system lumbers on because Justice is “meted by profound intuition.” In a short crisp paragraph Tejpal lays bare the functioning of the criminal justice system in India:

“The grandmasters of justice peer into the souls of wretches and spot the guilt where facts cannot be seen. They then punish by withholding judgment till the condemned have spent years inside the iron bars and paid for crossing every line drawn by men since they were born. The method is ingenious and worthy of an ancient civilisation. The guilty pay even when their crime cannot be proved. They learn the perils of wrongdoing. The innocent are finally acquitted even if it takes years. They are humbled by the miracle of justice. Sometimes the innocent are convicted: The seed of their badness caught before it can flower.”

The great Urdu poet Akhtar Ul Iman used to say that I write “for the defeated and the damned.” This novel too is an ode to the defeated, but who are far from crushed. It is about the brotherhood of the condemned and the heavy burden of grief because as a rule, “displays of grief in the iron realm were scotched brutally. This was the kingdom of loss. Every boy had a lament sheet long as an arm tucked inside his boxers. That is where it had to be kept. To be dealt with privately. Real grief multiplies if it is carelessly aired.”

The bars rarely elevate a person as most would leave “this world of iron either hopelessly broken or filled with venom. Most for the remainder of their lives would either add nothing to the sum of this world or would burden it with great despair.” But still, broken hearts achieve a functioning peace too. As another great writer observed how else ‘but through a broken heart, May Lord Christ enter in?’ In The Ballad of Reading Gaol Oscar Wilde asserts, in unison with the Bible that, ‘a broken and a contrite heart The Lord will not despise.’

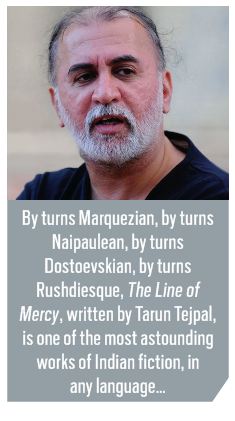

Tejpal’s novel is a dramatized account of hundreds of lives, which have themselves been marked by highly dramatic, cinematic even, turns and twists and therefore melodrama is to be valued here for how else does one read lives tumultuously turned upside down. By turns Marquezian, by turns Naipaulean, by turns Dostoevskian, by turns Rushdiesque, The Line of Mercy is one of the most astounding works of Indian fiction, in any language, of the recent years. It lays plain its intent in one of the most remarkable opening lines that one has recently read:

“Men judge others to absolve themselves. There is no intoxicant in the world quite as heady as sanctimony. All pleasure is a laburnum bloom—gone in a blinding burst. But righteousness has the enduring warmth of an ever-regenerating banyan. It grows fresh limbs. It creates its own forest. Men created god out of a fever of sanctimony. It is why he is always better at punishing than forgiving.”

We live in the age of sanctimony, and therefore can’t. No doubt the righteous do not want Tejpal rearing his head ever. Like the crowds at public executions, they are insatiable. Tejpal knows that the most successful entertainment in the history of mankind “is not the movies. It is public executions.” The sanctimonious no doubt will want to cancel this novel as they like to cancel everybody and everything that transgresses their code. Unlike the most brutal of Gods, they like to not just punish, but also to cancel culprits in entirety, to efface their existence if they can. The righteous may prevail for the moment, they may succeed in ignoring this monumental work. But one draws solace from the fact that The Line Of Mercy is a book that shall endure long after present day denouncers and necromancers, and their sanctimony, have passed into oblivion.

—Mahmood Farooqui is a Delhi based writer and performer, best known for reviving Dastangoi, the lost Art of Urdu storytelling. He has been a Rhodes Scholar, the winner of the Ramnath Goenka award for non-fiction for his book Besieged: Voices from Delhi, the recipient of the Ustad Bismillah Khan Award by the Sangeet Natak Akademi, and has been a Visiting Fellow at the Universities of Michigan and Berkeley, California