By Inderjit Badhwar

India Legal magazine, as I wrote in my previous column (read here), ever since its inception has never been a bandwagon jumper. We do not leap blindly into taking positions on national issues just because other publications and the electronic and social media, political leaders and self-proclaimed pundits are speaking in the same voice. We do not follow the brand of investigative journalism in which a newspaper or magazine first targets an editorially agreed upon individual or an institution, pursues its quarry for several months and then lets loose a barrage at an opportune moment, using the time spent on the story to solicit advertising and revenue support from vested interests seeking either protection from the hunt or having an interest in the outcome.

We do not follow the leader, so to speak. But we do follow the cardinal tenet on which India Legal was founded. We protect good journalism which, in today’s cacaphonic diatribes, seems to have become an oxymoron. It is for this reason that we stayed away, until now, from publishing the story of Sushant Singh Rajput’s death and its aftermath. As an unfolding story with strong legal ramifications and reverberations, it was tempting for us to dive into it and exult in self-professed “scoops”. In fact, a couple of weeks ago, we had prepared an “exclusive”, but we held it back because we thought it better to write a sober, insightful and scrupulously researched account reflecting our commitment to responsible journalism rather than competing with the bafflegab assaulting our sense and sensibilities from every possible news outlet.

Editorial Group Chairperson Rajshri Rai provided valuable insights and guidance as we put our senior team, led by the evergreen Managing Editor Dilip Bobb, assisted by veterans Shobha John, Sujit Bhar, Prabir Biswas, Sanjay Sinha, Srishti Ojha, Amitava Sen and Kh Manglembi Devi, to the task of reporting and assembling this multi-dimensional editorial package into a comprehensive whole.

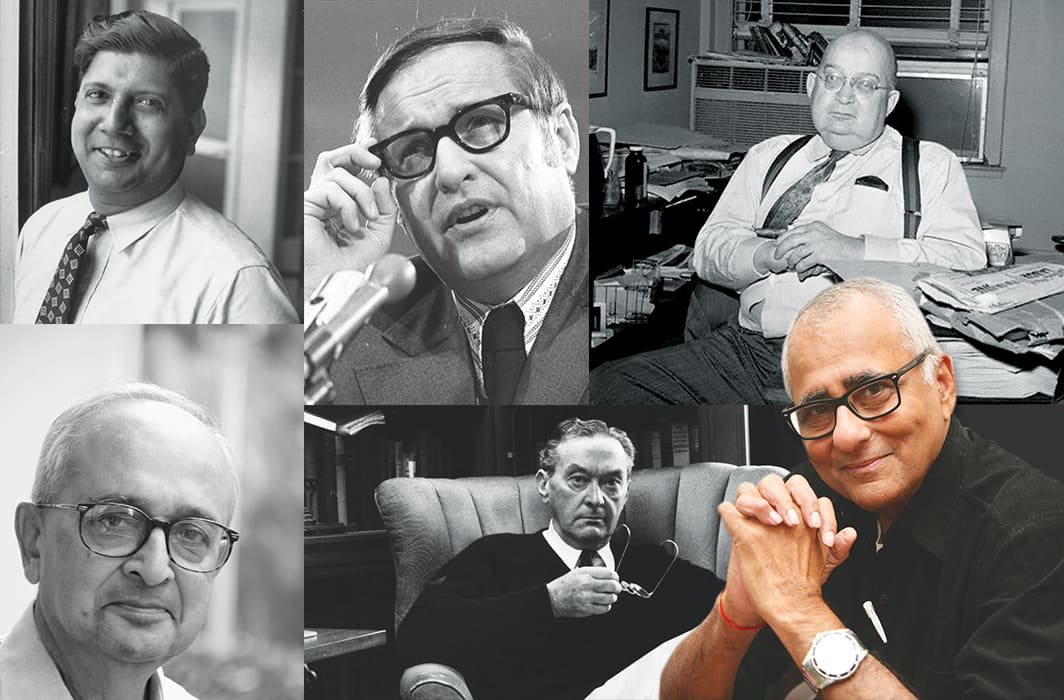

Actually, this is an old fashioned exercise which, in my view, represents the best example of what solid, responsible journalism used to look like when at its best and what all young journalists should be taught to practise. I’ve been an editor for some 40 years and I’ve been lucky enough to have learned from and taught some of the best in the business. A good editor, I was always told, is no different from a responsible and stern schoolmaster whose only satisfaction is the glory of those who have learned from him. Some of the best—the profession’s icons—I have had occasion to know or learn directly from include Frank Moraes under whom I was a correspondent at The Indian Express, Nandan Kagal, Inder Malhotra, Kuldip Nayar, Pran Chopra, George Verghese, and American greats Jack Anderson, Fred Friendly, Mike Wallace, Seymour Hersh, Clark Mollenhoff and Leonard Robinson.

And many others…who considered journalism a hallowed profession whose integrity was to be valued as nothing less than a holy grail. I was merely their conduit in passing along what they had bequeathed me to my own reporters and junior editors I have been fortunate enough to supervise as an editor of various publications and TV channels in India. There were some cardinal tenets we followed as articles of faith. They formed our code of conduct, our allegiance to our own version of the Hippocratic Oath: Tell it like it is. Don’t try and write a story for your readers unless you fully understand it yourself and are prepared to defend the facts. Always get both sides of the story, casting out your own prejudices. Don’t jump to half-baked conclusions. If you cannot be objective, you can at least be fair. News is not a propaganda delivery system. Learn to differentiate between an editorial, a story, an analysis and an opinion: A story is the narrative you put together with the facts, documentary evidence, interviews you gather—what we call khabar; an editorial is the position your media outlet takes on a controversy and is confined to the edit page; an analysis is an examination or breakdown of why something occurred; an opinion is a personal point of view on a controversy.

If you look at the way the Indian media has covered the Sushant Singh Rajput story, you will see that every code of honour and professional ethics that the standard bearers of my generation had upheld in order to keep our professional flag flying higher than that of the institutions we covered—because that is what we owed to the public—has been violated and damaged. As you leaf through different aspects of our cover story, you will be struck by Dilip Bobb’s trenchant analysis—with horrifying examples—of how the Indian media has behaved.

Writes Dilip: “It was all so tragically absurd, so patently false, so desperately competitive and so ethically and morally indefensible, that history will record it as the lowest point in the journey of Indian journalism. The current case has taken media coverage to new highs, or new lows to be more precise, and exposed the industry for what it really is; a ravenous beast with an insatiable appetite for sensationalism and speculation, where truth and facts have been sacrificed on the altar of TRPs.

“Here’s the proof. Between July 24 and July 29, according to the BARC survey, Republic TV conducted 45 out of 50 debates on the Rajput case. In contrast, it had one debate on the NEET/JEE student protests and exactly one on the coronavirus crisis which was then breaking new infection records. The result: Republic TV gained a 50 percent market share. Here’s the darker side of the TRP story: those figures would not be possible if the audience for such journalism did not exist. That is as sad a commentary on Indian society as it is on the media outlets that provide such salacious and provocative content, ignoring the reality of the life and future of a young woman (Rhea Chakraborty) being destroyed in the process.”

Our writer was echoing the observations of the great Walter Lippmann, author of the classic Public Opinion more than a generation ago. Lippmann’s point is that voter preferences are based “not on direct and certain knowledge but on pictures” given to us, writes Sean Illing in Vox. The question is then, where do we get our pictures? The most obvious answer is the media. If the media can provide accurate pictures of the world, citizens ought to have the information they need to perform their democratic duties. Lippmann says this works in theory but not in practice. The world, he argues, is big and it moves fast and the speed of communication in the age of mass media forces journalists to speak through slogans and simplified interpretations. (And this doesn’t even touch the problem of partisanship in a commercialised media landscape.)

Lippmann cites a famous passage from Plato’s Republic that describes human beings as cave-dwellers who spend their lives watching shadows on a wall and take that to be their true reality. Our present condition is scarcely different, Lippmann implies. We’re locked in a cave of media misrepresentations and we take our caricatured pictures of the world to be an accurate reflection of what’s actually happening.

“News and truth are not the same thing,” says Lippmann. The press, he says, is like a roaming spotlight, bouncing from topic to topic, story to story, illuminating things but never fully explaining them. “The function of news,” he writes, “is to signalise an event, the function of truth is to bring to light the hidden facts, to set them into relation with each other, and make a picture of reality on which men can act.”

Peter Vanderwicken, writing in the Harvard Business Review, looked at three books on this subject—News and the Culture of Lying: How Journalism Really Works by Paul H Weaver (The Free Press, 1994); Who Stole the News?: Why We Can’t Keep Up with What Happens in the World by Mort Rosenblum (John Wiley & Sons, 1993); Tainted Truth: The Manipulation of Fact in America, Cynthia Crossen (Simon & Schuster, 1994).

Journalists and politicians have become ensnared in a symbiotic web of lies that misleads the public, he states flat out. The news media and the government have created

“a charade that serves their own interests but misleads the public. Officials oblige the media’s need for drama by fabricating crises and stage-managing their responses, thereby enhancing their own prestige and power. Journalists dutifully report those fabrications. Both parties know the articles are self-aggrandising manipulations and fail to inform the public about the more complex but boring issues of government policy and activity”.

What has emerged is a culture of lying.

“The culture of lying,” he writes, “is the discourse and behaviour of officials seeking to enlist the powers of journalism in support of their goals, and of journalists seeking to co-opt public and private officials into their efforts to find and cover stories of crisis and emergency response.”

He observes that the media’s focus on façades has several consequences: One is that news can change perceptions, and perceptions often become reality. Adverse leaks or innuendos about a government official often lead to his or her loss of influence, resignation or dismissal. The stock market is also fertile ground for planted stories. Rumours or allegations spread by short-sellers often drive a stock’s price down.

He concludes that there may be nothing wrong with either the official’s performance or the stock’s value, but the willingness of the press to report innuendos and rumours as news changes reality. The subjects of such reports, which are usually fabrications created by opponents, must be prepared to defend themselves instantly. The mere appearance of a disparaging report in the press changes perceptions and, unless effectively rebutted, will change reality and the truth. That is why government officials and politicians—and, increasingly, companies and other institutions—pay as much attention to communications as to policy.

The American Press Institute, in its book The Elements of Journalism by Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, identifies the essential principles and practices of journalism. Here are elements common to good journalism, drawn from the book:

- Journalism’s first obligation is to the truth. Good decision-making depends on people having reliable, accurate facts put in a meaningful context. Journalism does not pursue truth in an absolute or philosophical sense, but in a capacity that is more down to earth.

- “All truths—even the laws of science—are subject to revision, but we operate by them in the meantime because they are necessary and they work,” Kovach and Rosenstiel write in the book. Journalism, they continue, thus seeks “a practical and functional form of truth.” It is not the truth in the absolute or philosophical or scientific sense but rather a pursuit of “the truths by which we can operate on a day-to-day basis”.

- This “journalistic truth” is a process that begins with the professional discipline of assembling and verifying facts. Then journalists try to convey a fair and reliable account of their meaning, subject to further investigation. Journalists should be as transparent as possible about sources and methods so audiences can make their own assessment of the information. Even in a world of expanding voices, “getting it right” is the foundation upon which everything else is built—context, interpretation, comment, criticism, analysis and debate. The larger truth, over time, emerges from this forum.

- As citizens encounter an ever-greater flow of data, they have more need—not less—for suppliers of information dedicated to finding and verifying the news and putting it in context.

On a personal note, among my favourite journalism gurus is the inimitable, irascible AJ Liebling, who wrote for various top American journals, including the prestigious New Yorker. John MacFarlane describes him as “an elegant writer—he said he could write better than anyone who could write faster, and faster than anyone who could write better—and a trenchant critic”. “There are three kinds of writers of news,” he once observed. “They are: 1) The reporter who writes what he sees. 2) The interpretive reporter, who writes about what he sees and what he construes to be its meaning. 3) The expert, who writes about what he construes to be the meaning of what he hasn’t seen.” Liebling was a stalwart interpreter and sceptical observer of the press, which he famously described as “the weak slat under the bed of democracy”. As MacFarlane concludes: In the end, the fate of the press lies in the hands of the press: either it embraces the responsibility to regulate itself, or the task will fall to others. Use it or lose it.