The Supreme Court refuses to accept the Congress’ plea that the governor of a state is bound to invite the single largest party in a hung assembly even if it does not have the numbers

~By Venkatasubramanian

The Congress was caught napping in Goa even as the BJP smartly stitched up the numbers to claim the chief ministership by burning the midnight oil there. Therefore, the result of the confidence vote in Goa on March 16, held under the direction of the Supreme Court, was a foregone conclusion. The BJP-led government, headed by Chief Minister Manohar Parrikar comfortably won the vote, securing the support of 22 MLAs in the 40-member House.

The Congress, which emerged as the single-largest party in the state with 17 seats, clearly lacked the numbers, while the BJP with just 13 seats could stitch a post-poll coalition with three regional parties—Goa Forward, Maharashtra-wadi Gomantak Party and the Nation-alist Congress Party, apart from two Independents. It did so well in time to stake its claim to form the government before the governor.

AICC General Secretary Digvijaya Singh, who faced flak for his handling of the Goa situation, tried to absolve himself from blame by claiming that his proposal for a pre-poll alliance with Goa Forward was “sabotaged” by his own party leaders. “As a strategy I had proposed a secular alliance with regional party headed by Babush Monserratte and Goa Forward head-ed by Vijai Sardesai,” Singh said in a series of tweets.

“Our alliance with Babush went through and we won 3 out of 5 but our alliance with Goa Forward was sabotaged by our own leaders. Sad!” he said.

” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:20px|text_align:left|color:%23000000″ google_fonts=”font_family:Open%20Sans%3A300%2C300italic%2Cregular%2Citalic%2C600%2C600italic%2C700%2C700italic%2C800%2C800italic|font_style:700%20bold%20regular%3A700%3Anormal”]

It was a repeat story in Manipur, where the Congress emerged as the single-largest party, winning 28 of the 60 seats in the assembly. Yet, the BJP, with 21 seats, managed to secure the support of 10 other MLAs—four each from two regional parties, and one each from the Lok Janashakthi Party of Ram Vilas Paswan and the Trinamool Congress.

The Congress, which found itself upstaged by the BJP in the numbers game in both states cried foul, and complained that its mandate was stolen by the BJP. In the Supreme Court, the Congress made a last-ditch attempt to stop the swearing-in of the Parrikar government by filing a writ petition. “Under what grounds can we stay the swearing-in of the new government?” asked Justice Ranjan Gogoi, one of the three judges of the Supreme Court, while hearing a petition of Goa Congress Legislature Party leader, Chandrakant Kavlekar, where he challenged Goa governor Mridula Sinha’s decision to appoint Parrikar as CM. Kavlekar sought the quashing of the governor’s decision as it was taken without consulting him as the leader of the single largest party after the assembly elections.

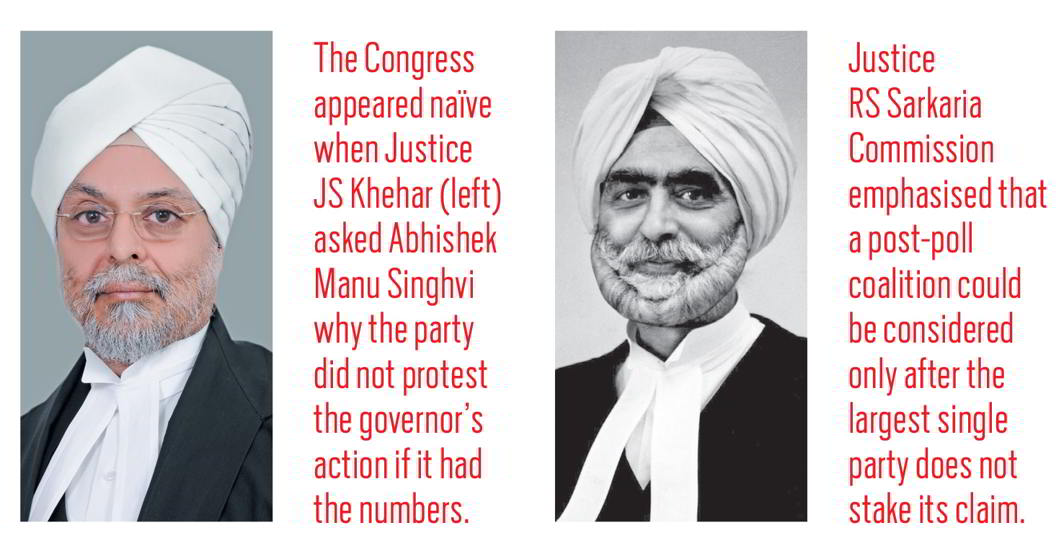

The three-judge bench, headed by Chief Justice JS Khehar, assumed that the Congress did not have the numbers to stake its claim to form the government, and did not dispute Parrikar’s claim to form the government either. The convention of inviting the single-largest party is relevant only when you have the numbers, the bench reasoned.

The bench told Singhvi that the largest party should be invited if there is no other group which can provide an alternative. In Goa, the bench pointed out that the Congress did not stake claim to form the government, whereas the BJP gave a list of 21 MLAs to the governor and produced all the supporting MLAs before her.

The Supreme Court bench believed that by advancing the date for the vote of confidence of the newly-constituted House to March 16 it could limit the scope for adoption of unfair means by the government in power. Obviously, the principle of democracy, considered the basic feature of the constitution, was the ground which the bench invoked to ensure a floor test at the earliest.

Constitutional experts told India Legal that the governor cannot simply assume that the largest single party is not keen on staking its claim or would be unable to do so because it lacks numbers or its leader has not yet knocked the doors of Raj Bhavan. The governor has to exhaust this option by inviting the leader of the largest single party for a discussion on the issue of government formation, they say.

On the contrary, by swearing-in seven MLAs—three of the Goa Forward Party, two of the Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party and two Independents—as ministers whose very support to the new government was yet to be demonstrated on the floor of the House, the Parrikar government had achieved a fait accompli and reduced the vote of confidence to a farce.

Constitutional niceties and the demands of maintaining separation of powers perhaps required the Supreme Court not to explicitly stay the swearing-in ceremony. But the order was silent on it, and its silence was construed as permission to go ahead with it.

On March 14, the Supreme Court was not inclined to consider the plea that the governor’s invitation to Parrikar was a violation of the electoral mandate as the ruling BJP has been reduced from its strength of 21 members to 13 in the assembly. Therefore, the Court had no answer to the plea that the BJP’s effort to cobble up a post-poll alliance with parties which were opposed to it during the elections, was against the democratic principle. However, it is this respect for the mandate of the people which made both the Sarkaria Commission and the Punchhi Commission on centre-state relations emphasise that a post-poll coalition of parties could be considered only after the largest single party does not stake its claim.

Constitutional experts told India Legal that the governor cannot simply assume that the largest single party is not keen on staking its claim or would be unable to do so because it lacks numbers or its leader has not yet knocked the doors of Raj Bhavan. The governor has to exhaust this option by inviting the leader of the largest single party for a discussion on the issue of government formation, they say.

This is what the senior counsel for Kavlekar, Abhishek Manu Singhvi, told the Supreme Court in vain on March 14. What Mridula Sinha did was reward the person who jumped the queue only because he claimed and submitted proof of support in the assembly.

The Congress appeared naïve when Justice Khehar repeatedly asked Singhvi why the party did not protest the governor’s action by sitting in dharna if it had the numbers. Singhvi told the bench that parading MLAs before the Raj Bhavan, once rebuked by the Supreme Court in the landmark Bommai judgement in 1994, would have been pernicious argument. The bench remained unconvinced.

“If you have majority, give us a list; we will pass an order,” the bench told Singhvi. It asked if there is a group of MLAs who have a majority, is the Governor bound to invite the single largest party, and said the Court had made it clear in the Arunachal Pradesh case last year that the governor could use her discretion in such situations.

The Supreme Court bench believed that by advancing the date for the vote of confidence of the newly-constituted House to March 16 it could limit the scope for adoption of unfair means by the government in power. Obviously, the principle of democracy, considered the basic feature of the constitution, was the ground which the bench invoked to ensure a floor test at the earliest.

Singhvi’s reliance on the reports of Sarkaria Commission (1988) and the Punchhi Commission (2010) was of no use either to convince the Supreme Court, whose previous constitution benches had endorsed these reports in successive cases. Both these reports had required the Governor to invite the single largest party, in the event of a hung assembly, where there are no pre-poll allies claiming majority support. Only if the single largest party declines the offer, then the Governor must invite any post-poll allies who claim majority support, the reports had recommended.

It would be an academic exercise to speculate whether the Congress would have been in a position to manage the numbers if the governors in Goa and Manipur had granted it the first opportunity to form governments there. At least, they could have avoided facing the criticism that they played partisan roles.