Above: The Delhi High Court

A petition, filed by a retired high court judge, seeks parity in pensions vis-a-vis judges who have been elevated from the Bar and those promoted from the lower judiciary

~By Vinay Vats

One Rank One Pension (OROP) was a resounding battle cry heard last year from Delhi’s iconic Jantar Mantar where armed forces’ veterans were demonstrating for the same pension for the same rank, for the same length of service. The demand for pay-pension equity underlies the OROP concept which has now found an echo in the hallowed precincts of the Supreme Court. A bench of Justices J Chelameswar and Sanjay Kishan Kaul has referred a petition for “one rank one pension” related to judges of the high court to a larger bench. The petitioner, not surprisingly, is a retired judge of the Madras High Court, Justice M Vijayaraghavan.

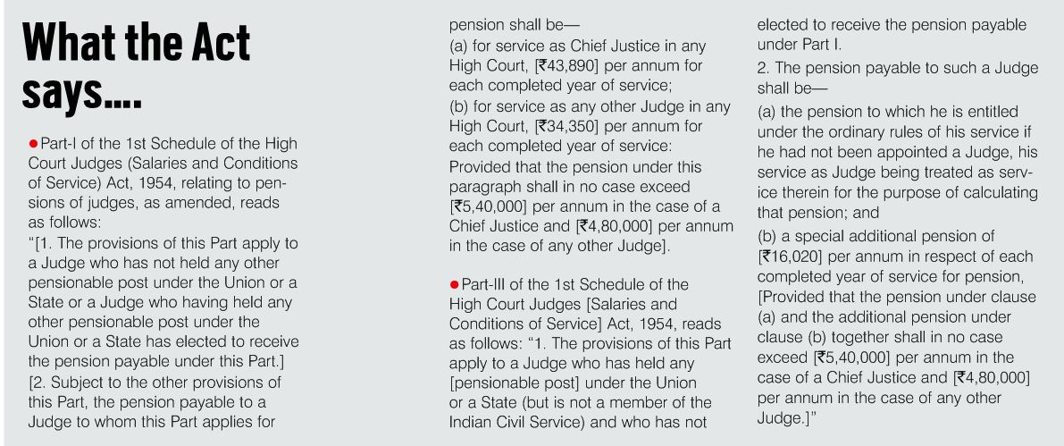

In his writ petition, he seeks to declare certain provisions of the High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Service) Act, 1954, null and void. The petition also seeks a writ of mandamus to rectify some irregularities in the pension payable to retired judges of high courts. The main grievance raised by the petitioner is that judges who have been elevated from the Bar are in a better position, financially, than those who have been promoted from the lower judiciary to the high court.

The pension of retired high court judges is governed by the High Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Service) Act, 1954. Earlier, some high court judges who were elevated from the Bar had complained about discrimination in pension. Judges elevated from the judicial service got almost a full pension even if they had worked as high court judges for only a few years. Their entire tenure as a judge in the subordinate judiciary was counted along with the period as a high court judge for computing the pension. In the case of judges elevated from the Bar, the pension was less because it was based only on the years they served as judges in the high court.

The issue was raised in the Supreme Court of India in 2002 in P. Ramakrishnam Raju versus Union of India when seven petitions were together filed by former judges of various high courts and the association of retired judges of the Supreme Court and high courts. The issue revolved around the plea that the difference in benefits of judges was in violation of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution of India and “one rank one pension” should be followed for any constitutional office.

A three-judge bench of then Chief Justice of India P Sathasivam, Justice Ranjan Gogoi and Justice NV Ramana had held that “when a person who occupied the constitutional office of Judge, High Court retires, there should not be any discrimination with regard to the fixation of their pension. Irrespective of the source from where the judges are drawn, they must be paid the same pension just as they have been paid same salaries and allowances and perks as serving judges”.

It was also observed in that case that “the experience and knowledge gained by a successful lawyer at the Bar can never be considered to be less important from any point of view vis-a-vis the experience gained by a judicial officer. If the service of a judicial officer is counted for fixation of pension, there is no valid reason as to why the experience at Bar cannot be treated as equivalent for the same purpose”.

It was further observed by the Supreme Court that “when persons holding constitutional office retire from service, making discrimination in the fixation of the pensions depending upon the source from which they were appointed is in breach of Article 14 and 16(1) of the Constitution of India. One rank One Pension must be the norm in respect of a Constitutional Office”.

Subsequently, the High Court and the Supreme Court Judges (Salaries and Conditions of Service) Amendment Act 2016, was implemented, amending the earlier High Court Judges Act of 1954 and Supreme Court Judges Act of 1958. According to part three of the amended Act, pension payable to the judges promoted from the subordinate judiciary shall be the pension which they would have drawn under the ordinary rules of the subordinate judiciary if he/she had not been appointed a high court judge. Now, the issue which has arisen is to do with the fact that pensions payable to district and sessions judges differs from state to state as they are governed by state pension rules which are not uniform.

The basic premise behind the latest petition is that judges of the constitutional courts are those who have left lucrative careers in the legal profession. This entails a big cut in their income apart from transfers out of their parent state high court. In the case of retired Supreme Court judges, they cannot return to the legal profession after retirement at 65 years, which is when a lawyer is often at the peak of his/her career.

Former Chief Justice of India TS Thakur had said, in his retirement speech, judges should be allowed to return to the legal practice rather than be made to retire and live on a pension. He would love to practise as a lawyer, he added.

The latest petition comes against the backdrop of the government’s proposal to hike salaries and pensions of judges based on recommendations of the Seventh Pay Commission. Despite the hike, the discrimination between pensions of high court judges based on whether they were elevated from the Bar or the lower judiciary, is clearly a sore point. Which is why OROP is being heard again.

—The writer is an advocate