Jaipur: On the second day of hearings at the Rajasthan High Court, two senior advocates gave contrasting arguments over whether courts have any jurisdiction over the disqualification of any member of a Legislative Assembly.

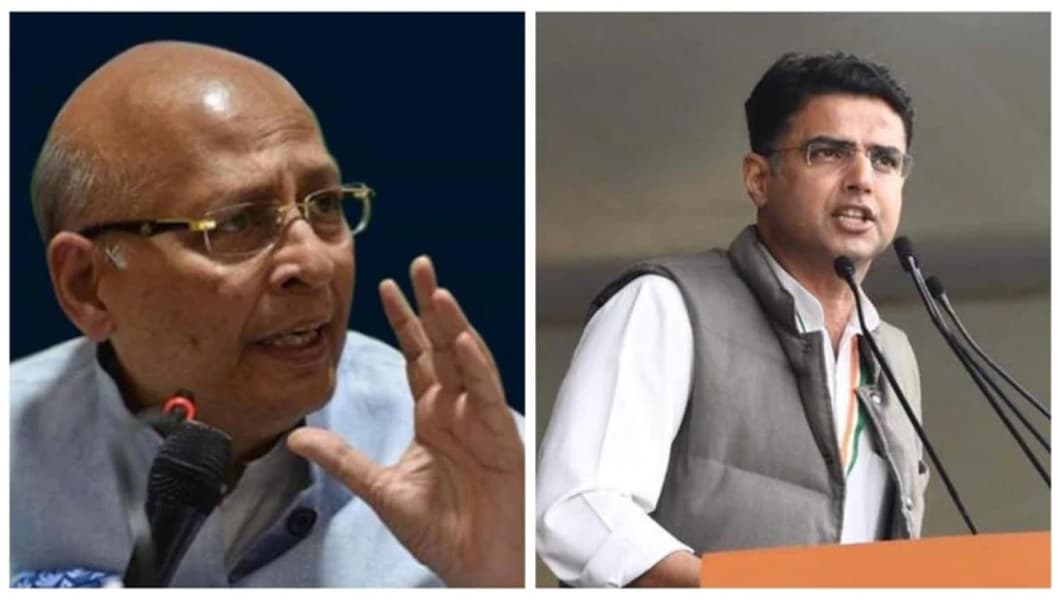

The court is hearing submissions in the petition filed by dissident Congress MLAs, led by Sachin Pilot. While Senior Advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi, arguing for the Rajasthan Assembly Speaker, said that courts have no jurisdiction, Senior Counsel Harish Salve, arguing for Pilot and the dissenting MLAs, said that the court can surely decide to interfere.

Pilot, the sacked Deputy Chief Minister of Rajasthan, and his supporter MLAs of the Congress have moved the court against the disqualification notices issued by the Rajasthan Assembly Speaker.

The other important issue was the whip. It was argued by Salve that a whip should be restricted to within the Assembly and would not apply to any party meeting. Hence the assumption that the ‘rebels’ were essentially giving up the party was wrong.

The issue comes up for the third day’s hearing tomorrow morning.

Approximately around 10.15 am today (July 20) the Rajasthan High Court resumed hearing of the petition against the disqualification notices issued by the Rajasthan Assembly Speaker.

Starting the day, Congress Spokesperson and Senior Advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi argued that a disqualification procedure is beyond the purview of the court. He said the courts have no jurisdiction over the disqualification of any member and that judicial review is absolutely barred in this case.

As an example, he talks about the Jharkhand case and others and presented a hypothetical case as: “What will happen if the Speaker orders video recordings of court proceedings?” he cited two more judgments on jurisdiction, the 2016 Amrita Rawat And Others vs Speaker case where the court had dismissed a petition challenging show cause notice of the Speaker of the Uttarakhand Legislative Assembly. He also presented before the court the Devinder Sehrawat AAP MLA case. He also cites the Keisham Meghachandra Singh (authored by J Nariman) case, trying to buttress his argument on the limits of the high court’s jurisdiction.

He said there is no cause for action on the writ until the Speaker takes a decision on the disqualification notices.

He went on to say that the Supreme Court, in the 1992 Kihoto Hollohan case, had rejected the arguments raised by senjior Advicate Harish Salve (representing Pilot and others) against the Tenth Schedule. The Tenth Schedule was upheld as a reasonable restriction on free speech, Singvhi argued.

He added that the same arguments, considered and rejected by the SC (in the above case), are being raised by Salve against the constitutionality of paragraph 2(1)(a) of the Tenth Schedule. He said that freedom of speech of a member is not an absolute freedom. He said that the SC had had held that too in the Kihoto case. He said the settled position cannot be reopened by the High Court, adding, that the high court cannot be asked to re-look at a constitution bench decision of the Supreme Court as in the in Kihoto Hollohan case.

Singhvi added: “’Unprincipled defection is a political sin and against constitutional morality’, was the SC’s observation in that judgment.”

‘The Speaker has the right to be wrong’

He argued that the Speaker can be right, or be wrong. “The Speaker has the right to be wrong,” he said. Taking a technical point, Singhvi said: “This petition is based on the show-cause notice issued by the Speaker. Unless the Speaker has disqualified you, you cannot approach in the interim.”

He said the current case is “much worse”, as there are no new grounds of challenge, and that the petitioners, in an “over-clever” way, have raised the same grounds of challenge, which were considered and rejected by the Supreme Court the Kihoto case.

He said that an interim order staying the Speaker’s notices will amount to a stay on the operation of paragraph 2(1)(a) of the Tenth Schedule. This, he said, cannot be done. Then, quoting SC orders, he said that in matters involving constitutional challenges, courts should be extremely loathe to stay the provisions. “The operation of statutory provisions cannot be stultified in the interim,” he said.

He said that the Speaker is yet to decide on the matter. Just the show-cause notice cannot be stayed. He said that the questions of facts in the notices against 19 MLAs are yet to be decided. He said that there will be different facts associated with each of the 19 MLAs’ displeasure. He said that each matter has to be decided by the Speaker, case-to-case basis. Therefore, Singhvi argued, the Speaker’s exercise of power cannot be interdicted at this juncture.

Explaining this, he said that each MLA’s support is crucial in a government. He said: “Smaller the state, higher the value of each MLA. This is because in a smaller Assembly, the switch of one or two MLAs can be costly.” In support of this he cited the Goa assembly case, where Congress had lost out on a rather slender margin.

He said that the Speaker will be violating the law if he does not act under Tenth Schedule in the instant case.

At this point he also touched upon the membership issue. He said that the issue of voluntary giving up of party membership should be read widely. He added that there is no need for formal resignation (as pointed out by India Legal in this story). He said that giving up of membership can be inferred from the member’s conduct. In this he was quoting from the SC decision in Ravi Naik case (1994).

Singhvi referred to a constitution bench decision in (2007) 4 SCC 270 (para 48, 49) to insist that there was no fixed approach for the Speaker to decide under Para 2(1)(a). He said that while there was no fixed path or formula, the how the Speaker takes his decision remains within the Speaker’s domain.

He said that non-attendance in party meetings may or may not amount to voluntary giving up of party membership. He said this will depend on the facts. He said that the Speaker has to be given the opportunity to decide on that.

Referring to the Karnataka MLAs’ disqualification, upheld by the apex court, her said that failure to attend the party meeting was also a ground for attracting defection under Para 2(1)(a).

‘This is pre-empting that the Speaker will take a wrong decision’

He reiterated that the Speaker may or may not pass a correct decision, but there cannot be any interference at the pre-order stage, preempting that Speaker will take wrong decision.

Then Singhvi went on to the time-limit mentioned in the show-cause notice. This was also one point that the petitioners had mentioned, as being rather short. The petitioners’ said the two-day time limit violated Rules which mandate 7 days.

To that Singhvi said that a mere violation of rules, if any, will not void the Speaker’s decision. He went back, again to SC rulings, quoting that natural justice is not dependent on the number of days given for response. The Speaker cannot shut his eyes to the developments happening fast, Singhvi argued.

Her said Ravi Naik (1994) was a case of the Speaker giving 2 days for reply, though rules mandated 7 days. But the SC upheld the Speaker’s decision.

He said the Constitution gives leeway to the Speaker to regulate the procedure. Rules are subordinate to the Constitution. Violation of disqualification rules are procedural and any violation of it immune to judicial review. “What prevents them from submitting a reply to the Speaker’s notice?” asked Singhvi.

Quoting from the Ravi Naik decision, Singhvi said: “Any violation of the disqualification rules will not give a ground to review the decision of the Speaker. In any case, in the instant case, the petitioners now have got seven days time to submit their reply.” He also said that the question was not on the number of days provided, but on whether ample opportunity was granted for giving the response.

He added that rules are in the domain in the procedure to facilitate the enquiry and cannot be used to invite technicalities to curtail the process. He said rules are directory in nature and not mandatory.

He also added that the decision in the Amar Singh case (2011) 1 SCC 210, cited by the petitioners, is irrelevant in the instant case, as it was not a case of disqualification. He also objected to the allegations of “mala fide” against the Speaker. He said: “(The) Petitioners are trying to ask the court to do indirectly, what it cannot do directly.”

The court, having resumed after recess, Singhvi summarized his first session submissions, before Chief Justice Mahanty asked if the Speaker is not required to make any application of mind before initiating proceedings under Tenth Schedule. “Are you suggesting that the Speaker, at the stage of issuing notice, is only required to see if the complaint regarding disqualification is in the proper proforma?” the Chief Justice asked Singhvi.

Singhvi said that the Speaker, on receiving such a complaint, will see if the allegations are broadly referable to the Tenth Schedule, and are not outlandish. “The Speaker is not like a post-office,” Singhvi replied.

At that the Chief Justice said: “Even if an outlandish complaint is made, is the Speaker is bound to issue notice?”

Singhvi said: “No, not at all. It has to be seen whether the complaint is broadly referable to Tenth Schedule.”

CJ Mahanty asked if the Speaker is bound to record reasons while issuing notice.

Singhvi says: “No, the Speaker is not bound to record reasons at the stage of notice.”

CJ Mahanty asked: “If the Speaker is rejecting the complaint without issuing notice, is he not bound to record notice?”

Singhvi said yes, but added that in the reverse scenario (recording reasons for notice) is not needed.

At that CJ Mahanty asked if there was any case law for that proposition.

At that Singhvi again cited Kihoto.

The CJ, however, disagreed, saying Kihoto was only with respect to constitutional validity of the Tenth Schedule. “In the absence of reasons recorded, what cause the person can show to avoid disqualification?” asked the CJ.

At that Singhvi reiterated that the court cannot interfere at the stage of show-cause. “How can the court decide on the sufficiency of reasons stated in the show-cause notice? The Speaker’s power is not comparable to other Tribunals; not like other ‘quasi-judicial bodies’.

Following Singhvi’s submissions, Advocate General M S Singhvi started his submissions. He mostly supplemented senior advocate Singhvi’s submissions.

Arguing for Congress, Senior Advocate Devadatt Kamat started his submissions. Meanwhile, Congress Party Whip, Mahesh Joshi, had been impleaded as additional respondent.

The membership issue

Kamat, referring to the reliefs sought for in the petition, said that the petition seeks a declaration that petitioners are members of the assembly by virtue of their continuation in the Congress party. “How can such a declaration be given?” he asked. “By their actions they have voluntarily given up the membership of party.”

The CJ asked: “Have you expelled them?”

At this Kamat replied: “Two of them have been suspended.”

CJ Mahanty asked how the disqualification proceedings and the suspension be juxtaposed. “Either they are members of your party, or not members. It cannot be both ways,” the CJ observed. “You say these members have voluntarily given up their membership of the party. Now you have issued suspension against them. The assumption behind suspension is that they are members,” CJ Mahanty observed.

At this Kamat submitted that initiation of disqualification proceedings cannot prevent disciplinary proceedings within the party. “They are to formally resign from the party, but their conduct will be construed as giving up party membership,” Kamat said.

Kamat submitted that the reliefs sought for are based on factual questions, and cannot be granted. He said that the validity of the proceedings in the House cannot be called into question by the court. The bar of Art 212 of the Constitution is there, he said.

Referring to a Full Bench decision of the Madras HC (reported in AIR 1969 Madras 10), Kamat said that the court refused to entertain a petition seeking writ of prohibition to prevent the Speaker from initiating contempt proceedings against a member for breach of privilege.

He referred to Para 6(2) of Tenth Schedule to state that disqualification proceedings are deemed to be proceedings within house within the meaning of Article 212 of the Constitution.

At one reference, CJ Mahanty objected to the use of word “pack of 19 MLAs” and said that it was offensive language. Kamat agreed to withdraw the remark and used the term “group of 19 MLAs” instead. He reiterated that it is for the Speaker to take a call on whether the acts of the 19 MLAs amounted to voluntarily giving up of party membership or not.

Regarding the MLAs not adhering to the party whip, CJ Mahanty said that the whip can be only with respect to the Assembly session. He said that a whip cannot be issued with respect to a party meeting.

Kamat said that the dissident MLAs had made open statements to bring down the government. He said the Speaker is the Master of the House. It is his primary jurisdiction to evaluate the facts and evidence.

Responding for the petitioners, Senior Advocate Harish Salve began his rejoinders but Singhvi intercepted, made a clarification regarding a query posed by the court earlier regarding the Speaker recording satisfaction before the show-cause notice.

Singhvi said that after the court’s query, he sought to see the files of the Speaker, and (saw that) detailed satisfaction has been recorded.

At this the court asked Salve if the hearing can be adjourned till tomorrow, but the senior advocate said that he had some difficulty tomorrow and sought an adjournment to Wednesday.

At this the bench requested Singhvi to contact the Speaker to ascertain if the time for reply can be extended beyond 5.30 pm on July 21 (Tuesday). At this Singhvi said that the Speaker was reluctant, saying that the time has been extended twice already. Singhvi said that the Speaker could defer the decision till Wednesday (July 22), provided the 19 MLAs file a reply by tomorrow.

Senior Advocate Salve resumed his rejoinder. He said that the Speaker, without hearing the petitioners, has already made up his mind. When Speaker appears before the court and argues vigorously for disqualification, it has to be inferred that he has already made up his mind, Salve said. “The Speaker has not limited himself to the allegations of mala fide made against him. The Speaker has argued that he can consider all materials.”

With this Salve took the bench through the Constitution Bench judgment in the Kihoto case. He said: “’Crossing the floor’ was the issue in Kihoto. Expressing dissent against a party chief is not ‘crossing the floor’. He is ‘staying on the floor’.”

He said that eminent jurist Nani Palkhiwala had criticized the Tenth Schedule. He added that the Chief Whip of the party sits inside the house and not outside. The whip is applicable only to house proceedings, he reiterated. “A mere act on inner party indiscipline cannot be regarded as giving up of party membership.”

He said Justice Venatachaliah had observed in the Kihoto judgment that this (inner party protest) is a grey area of 10th schedule. The 10th schedule law has to evolve, Salve said. He said that defection is when you leave Party A and joint Party B. Intra-party differences were not regarded as defection in the Kihoto judgment. He said intra-party debates are permissible.

He said that if a group of MLAs raise their voices against the style of functioning of the Chief Minister, that is not defection. In fact, the Kihoto judgment draws a marker with respect to inner party dissent. This cannot be regarded as “unprincipled defection”. He said ‘mala fides’ is a ground available to challenge the speaker’s decision, as per the Kihoto judgment.

Salve also pointed out that the Kihoto judgment does not absolutely bar interference of Court anterior to Speaker’s decisions. The judgment permits such interference in exceptional circumstances. In the present case, the fundamental point is that the Speaker had no jurisdiction to issue notice on the complaint of the Congress Whip.

Salve gave an example: “If a group of MLAs say that the party president is incompetent, and the party president complains to the Speaker that they have defected, and the Speaker issues notice for disqualification, can they not approach the Court against it?”

He said that even if the complaint allegations are assumed to be true, they will only constitute a case of inner party dissent. No case under 10th schedule. He said that issuing disqualification notice for inner party dissent is a violation of freedom of speech of the legislator. “If a law was made saying refusal to attend party meeting would amount to crossing the floor, your lordships will strike down that law.”

A party member is free to defy the party whip’s direction outside the house. Nowhere in the Kihoto judgment does it say that defying the party whip outside house amounts to defection. The statement that we will bring down the Chief Minister’s government and will make our own government with the same party is part of right to dissent.

Intra-party dissent, however shrill it may be, until the moment it goes to the extent of supporting another party, cannot be a ground to even start disqualification proceedings under the Tenth Schedule. I can’t argue these factors before the Speaker as he is already prejudiced. That is why I am before this Court, Salve said.

Quoting from the UK Supreme Court’s decision in the Parliament prorogation case, Salve said: “The fact that a legal dispute arises from the conduct of politicians is not a bar to courts in exercising jurisdiction.” Salve says “there is a difference in saying Courts will generally not interfere with Speaker’s decision and Courts have no supervisory power. Courts can exercise jurisdiction over the decision of Speaker.”

He said that If Speakers are permitted to act against legislators for speaking against the party chief, that goes against right to dissent.

As Salve concluded his arguments, the bench rose. It will hear Senior Advocate Mukul Rohatgi for petitioners tomorrow morning 10.30 am.

– India Legal Bureau