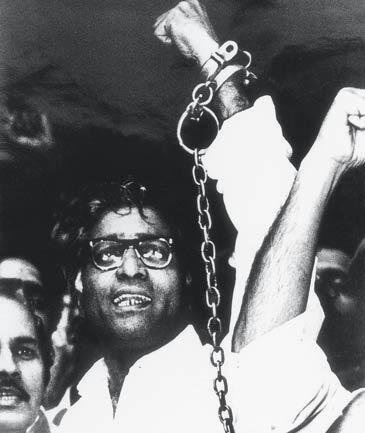

Above: After the Emergency, the SC introduced the “just, fair and reasonable” test in Article 21/Photo: IndiaHistorypic/Twitter

The constitution of a country is the supreme law—it is the source of all governmental power, legislative, executive or judicial. It is the law which delineates the regulation and management of power in governmental institutions. Apart from the inter-institutional dynamics, a modern democratic constitution has another important role to play—to provide fundamental guarantees and freedoms for every individual or community to live with dignity.

Despite being the lengthiest in the world, the Indian Constitution makers ensured that its flexibility is not affected due to its specificity. Its flexibility is evident from constitutional practice over the last 68 years and in particular, from the manner in which the Supreme Court has interpreted it to suit the needs of the times and by breathing life into it. There are also special provisions to enforce rule of law and constitutional mandate, viz. due process of law; public interest litigation; and the treatment of women, juveniles, senior citizens and mentally challenged persons.

DUE PROCESS OF LAW

The constitution-makers deliberately avoided the use of the term “due process” while guaranteeing the right to life and personal liberty. Article 21 provides that “no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”. The draft Article 15 (now Article 21) attracted considerable attention and polarised opinion both within the Constituent Assembly and outside. Eventually, the “due process” requirement on the lines of the American Constitution was dropped in favour of the phrase “procedure established by law”, which finds place in the Japanese Constitution. The entire exercise was undertaken to limit judicial review of the government’s powers, especially in the area of preventive detention. The bare reading of Article 21 is, thus, all that the State needs to do to deprive a person of his liberty.

This bare reading was reinforced by the Supreme Court in AK Gopalan v State of Madras, where the Court held that once there is a procedure established by a law, such a procedure will be immune from any judicial scrutiny.

However, the Supreme Court corrected itself. After the Emergency, it asserted itself and gave meaning to the right to life and personal liberty by introducing the test of reasonableness to this “procedure established by law” in Maneka Gandhi v Union of India. In other words, the Court can now test a procedure established by law on the anvil of it being “just, fair and reasonable” and it can strike down a procedure if it is found to be fanciful, oppressive or capricious.

The impact of the Maneka Gandhi case on Indian jurisprudence, and indeed judicial thinking, is so deep that it would not be an understatement to say that though the Constitution was conceived in 1950, its birth was in 1978 when this case came up. Decades later, Article 21 is a positive obligation to ensure that persons live with dignity and the high ideals of the Constitution are translated into meaning for an ordinary Indian’s routine existence.

PERSONAL LIBERTY

The Supreme Court has extended the ambit of Article 21 and this provision has been the cornerstone for strengthening the rule of law. A long list of cases decided on Article 21 is illustrative of the extent to which the Supreme Court has given importance to personal life and liberty. It has also extended the list of unenumerated Fundamental Rights.

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION

Once the Supreme Court paved the way in the Maneka Gandhi case for a liberal and meaningful interpretation of the rights charter, in SP Gupta v Union of India, the Court relaxed the requirement of locus standi in PILs. If we look at the text of Article 32 which bestows on every person the right to constitutional remedies, it is found that the requirement of locus standi is absent. It states: “The right to move the Supreme Court by appropriate proceedings for the enforcement of the rights conferred by this Part is guaranteed.” It does not specify who is required to approach the Court for enforcement of fundamental rights. Yet, it guarantees the right to get such rights enforced by the Supreme Court.

RULE OF LAW, EQUALITY AND JUDICIARY

In Dr Subramanian Swamy v Dr Manmohan Singh, Justice AK Ganguly observed that both rule of law and equality before the law are fundamental questions in the Constitution as well as in international rules. In this judgment, Justice Ganguly elaborates that Parliament should contemplate constitutional overbearing of Article 14 enshrining the rule of law wherein “due process of law” has been read into it by introducing a time limit in Section 19 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988.

SPECIAL LEGISLATION

- Gender Justice

The policies of the government are committed to enable women to be “equal partners and participants in development”. The Constitution guarantees equality of status of women and has laid the foundation for such advancement. It also permits reverse discrimination in favour of women and many important programmes that have been designed specifically to benefit girls and women. A number of laws have been enacted which have brought forth a perceptible improvement in the status of women. These include the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956; Hindu Succession Act, 1956; Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961; Maternity Benefit Act, 1961; Equal Remuneration Act, 1976; Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act, 1986; Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, 1994; Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, and Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006. The Criminal Amendment Act, 2012, framed under the Justice Verma Committee Report is another tool to ensure gender justice in India.

- Juvenile Justice

Realising the importance of juvenile justice in Sampurna Behrua v Union of India & Ors (2011), the Supreme Court observed that the Home Departments and DGPs of states/UTs will ensure that at least one police officer in every police station is given appropriate training and orientation and designated a juvenile or child welfare officer. He will handle the juvenile or child in coordination with the police as provided under sub-section (2) of Section 63 of the Act. The required training will be provided by the district legal services authorities under the guidance of the State Legal Services Authorities (SLSAs) and Secretary, National Legal Services Authority, will issue appropriate guidelines to SLSAs for training and orientation of police officers who are designated juvenile or child welfare officers. The training and orientation may be done in phases over a period of six months to one year.

An independent judiciary, independent constitutional review and the notion of the supremacy of law all work together to ensure that the letter and spirit of the Constitution are complied with in the working of a constitutional government. Rule of law, therefore, has been claimed as the most important constitutional principle. It is, therefore, heartening to note the working of the Constitution and the role of the Supreme Court in promoting the rule of law and enforcing justice.

— The writer is Vice-Chancellor, National Law University, Delhi