Above: Actress Diya Mirza with acid attack victim Laxmi at a youth conclave in Lucknow. Photo: UNI

Despite the fact that acid attacks are common in India, there is little succour for the victims as they battle social stigma, threats and medical problems. When will stringent laws give relief to victims?

~By Lilly Paul

India is one of the leading countries where acid attacks take place. According to 2016 data of the National Crime Records Bureau, there were 307 acid attack victims that year with West Bengal topping the list (83 victims), followed by UP (61) and then Delhi (23).

However, this crime is also prevalent in progressive societies such as the UK and in developing countries like Bangladesh. But the difference is that both these countries have successfully tackled the crime. According to reports, London witnessed 454 cases of acid attack in 2016, a 173 percent increase from 2015. In the first two months of 2017 alone, there were 49 acid attacks. London is attempting to take measures to curb the incidents and shopkeepers and the general public are supporting the police in the fight against this crime. In Bangladesh, there are strict laws to keep a check on the increasing incidents.

However, India has not been able to effectively tackle the issue nor has it been able to provide any relief to the victims. It was only in 2013 that the Indian Penal Code was modified to add Sections 326 (a) and 326 (b) for dealing with cases of acid attacks.

VICTIM COMPENSATION SCHEME

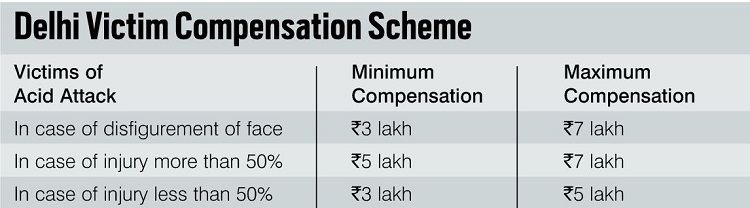

The District Legal Services Authority (DLSA) is entitled to disburse compensation to acid attack victims. Every state has a Victim Compensation Scheme of its own from which it has to pay a sum of Rs 3 lakh to the victims.

Before the Laxmi vs Union of India judgment where the apex court mandated that “a minimum of Rs 3 lakh” be made available to every acid attack victim, DLSAs would disburse meagre amounts between Rs 25,000 and Rs 1 lakh to the victims. This was because states were earlier following the Victim Compensation Scheme of 2011. For Delhi, the minimum compensation for disfigurement of the face was Rs 2 lakh and the maximum was Rs 3 lakh, whereas the compensation for any other form of injury related to an acid attack was Rs 50,000.

However, after the Laxmi judgment of 2013, there was a mandate on states to revise their schemes so as to fit in a minimum compensation of Rs 3 lakh. According to the revised rates, the maximum compensation for disfigurement of the face and injury of more than 50 percent is Rs 7 lakh in Delhi.

While Rs 3 lakh is the minimum compensation for acid attack victims, in the Parivartan Kendra vs Union of India judgment of the Supreme Court, it said that “the mandate… nowhere restricts the Court from giving more compensation to the victim of acid attack”.

As the rules are not uniform in the country, there is confusion among the DLSAs about how much compensation to award in such cases. The rules are different for the three states and one Union territory that top the list of acid attack cases. In Delhi, the compensation differs according to the severity of attack (see box). In Uttar Pradesh, Rs 3 lakh is the maximum limit of compensation. In West Bengal, Rs 3 lakh is the minimum limit of compensation.

Victims of acid attacks who came for APN’s India Legal Show:

Anu Mukherjee:

Incident December 19, 2004

Thirteen years ago, Anu Mukherjee was attacked with acid by one of her friends. She lost her eyesight and has had 22 surgeries for which she spent Rs 35 lakh. She is struggling with a debt of Rs 6 lakh.

Farah from Farooqabad (UP):

Incident February 2011

Farah was attacked by her husband because she had decided to break free from the daily torture of domestic violence. She filed for divorce in 2009 and was granted separation in 2010. But her husband attacked her with acid the next year. He was jailed for three-and-a-half years. Farah said it was a mockery of her pain.

Chandrahaas Mishra:

Incident 2011

In a country where sensitisation towards cases of acid attack on women is very low, Mishra faced even more insensitivity. He was attacked by the son of his landlord in Meerut because he stopped him from harassing women. His attacker was jailed for six months and was then granted bail. He threatened Mishra to withdraw the case or else he would do him more damage. Mishra, along with Acid Survivors and Women Welfare Foundation, now works for other acid attack survivors.

When Mishra approached the DLSA for compensation, he was handed Rs 1 lakh. The authorities said they had no instructions regarding a male acid survivor and this was the amount he could be given. For a person who spent Rs 12 lakh on surgeries, this compensation was a slight.

Sadly, the increase in compensation has not brought any real relief to the victims. This is because as per the State Legal Services Authority, while getting the compensation, every victim has to state in writing to the Authority that she shall refund the amount if courts later order the accused to pay any amount by way of compensation. This means that if the victim gets a compensation of Rs 3 lakh from the DLSA and at a later stage, the courts order the wrongdoer to pay a fine, this amount will be adjusted against what the DLSA has disbursed. If there is any amount left (after returning money to the DLSA), the victim can keep it.

As per the rules, the DLSA has to pay Rs 1 lakh to the victim within 15 days of the matter being brought to its notice and the remaining Rs 2 lakh within two months. “This practically never happens,” said Sija Nair Pal, an advocate with Human Rights Law Network. Victims who do not have any legal support to approach the court or are not aware enough to approach the DLSA suffer.

FREE MEDICAL TREATMENT?

Medical treatment is another hurdle. Victims from the poorer strata of society usually approach a government hospital for treatment but their condition leaves much to be desired. Also, while these hospitals do not refuse to treat the patients, they lack the infrastructure and expertise to do so.

Chandrahaas Mishra, an acid attack survivor and an area coordinator with the Acid Survivors and Women Welfare Foundation, told India Legal about the difference in treatment in private and government hospitals. He said he was attacked with acid which damaged his eyes. In an acid attack, the eyes fuse together, making the person partially or completely blind. But he was fortunate enough to be financially sound and got himself treated in private hospitals, after which he recovered well. “You can see the difference between my recovery and other patients’. At government hospitals, they do not take the extra challenge of correcting deformities, whereas in private ones, they do as you are paying a huge amount for the treatment.” With every surgery costing around Rs 2.5 to Rs 3 lakh, it is no wonder that many acid attack victims struggle to recover.

India could learn from Bangladesh when it comes to tackling acid attack cases. Between 1999 and 2002, acid attacks in Bangladesh increased by 50 percent. The government then passed two new laws in 2002—the Acid Offences Prevention Act, 2002, and Acid Control Act—to tackle the growing problem. Soon after the enactment of the two laws, there was a 15 percent decrease in cases of acid attack in 2003.

The government also took care of male victims while framing the law when it realised that they too were victims of this vicious crime. In fact, 30 percent of victims were men and the main reason was land disputes.

Bangladesh has strict and elaborate laws in place to deal with acid attacks and some of the provisions are:

- The total time given for investigation is 90 days.

- After 90 days, the trial and conviction have to be completed within 90 days.

- Acid Offences Prevention Tribunals which were set up solely to try cases of acid attacks were headed by district or session judges.

- The accused can be sentenced to death or be given rigorous imprisonment along with a fine in case the victim has vision or hearing damage.

- An attempt to throw acid on a person, irrespective of whether the act causes any physical, mental or other damage to the victim is punishable with imprisonment which may extend to seven years but not be less than three years along with a fine.

- The law also provides for action to be taken against a negligent doctor.

In Laxmi vs Union of India, the apex court had clearly mentioned that “full medical assistance should be provided to the victims of acid attack and that private hospitals should also provide free medical treatment to such victims”. But do private hospitals do so? Divyaloke Rai Chaudhari, coordinator of the Kolkata-based Acid Survivors and Women Welfare Foundation, laughed. “Not a single one of the renowned hospitals we approached in Kolkata agreed to treat the patients free,” said Chaudhari.

The Court had further ordered that these private hospitals should provide full treatment which includes “medicines, food, bedding and reconstructive surgeries”. The refusal to treat acid attack victims could lead to action being taken against the hospital.

Justice AK Tripathi, former judge of the Allahabad High Court, told India Legal: “If acid attack victims are admitted in any hospital, irrespective of whether it is a central, state or private hospital, it has to arrange for their treatment. How much they abide by it is an altogether different matter.”

The hospitals excuse themselves saying they don’t have the requisite infrastructure. This despite the Court saying that “no hospital/clinic should refuse treatment citing lack of specialised facilities”. Even if these hospitals take up a victim’s case, only basic treatment is given. “Many a time, they seem unaware of such a rule. Even if they come to know of it, they refuse, citing various reasons such as they don’t have a vacant bed or a specialised unit to treat the victim,” said Mishra.

Hospitals which take up free treatment for acid attack victims do it under their corporate social responsibility. However, it is not a CSR activity. The onus of getting such a patient treated lies on the hospital administration. “It is mandatory for the hospital to inform the police about an acid attack and when the police registers a case, it is the job of the police officer to inform the DLSA. It is an interconnected system, wherein if anyone fails in his duty, the victim suffers,” said Pal.

RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY

Every aspect of the recovery depends on the concentration of the acid that was used and the extent of penetration of the skin. The victim has to undergo numerous surgeries. But how much of the reconstruction is actually possible? “Very superficial damage only can be reversed,” said Dr Manoj Kumar Johar, Director and head of department, plastic surgery, Max Super Specialty Hospital. Recovery is difficult in second-degree or deep second-degree burns. Johar said there are three stages of recovery—form, function and looks. Priorities differ in every case. If it is the eye that has been damaged, then the focus would be to recover the function of the eye, whereas in the case of an ear, it would be recovering the form of the organ.

Recovery is difficult in second-degree or deep second-degree burns. Johar said there are three stages of recovery—form, function and looks. Priorities differ in every case. If it is the eye that has been damaged, then the focus would be to recover the function of the eye, whereas in the case of an ear, it would be recovering the form of the organ.

Disposing of the writ petition in the Parivartan case, the Supreme Court had ruled that an amount of at least Rs 3 lakh be given to the victims. The apex court had also directed all states and Union territories to consider the plight of such victims and take appropriate steps with regard to inclusion of their names under the disability list. The amended Rights of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2016, increased the types of listed disabilities from seven to 21 and acid attack victims were included in it.

The bill classifies acid attack victims as people with “physical disability” and disfigurement due to violent assaults by throwing of acid or similar corrosive substance. The bill says nothing about the degree of burns or the minimum damage that the victim should go through to avail of benefits.

However, when Mishra approached the authorities to get his disability certificate, he was informed that a person should have suffered at least 45 percent burns to be able to avail of benefits. Any person with less than that is not considered for award of the certificate. “Forty to 45 percent disability is the benchmark, so a victim below those levels of burns will not be issued a disability certificate,” said Pal.

ACCUSED IS FREE

In many cases, while the victims are scarred for life and struggle with their medical bills and social trauma, the accused goes scot-free and issues new threats to the victim. In the Mishra case, the accused got bail within six months whereas in Farah’s case (see box), the accused was put behind bars for just three-and-a-half years. This is traumatic for the victims as they live a life of rejection and seclusion, whereas the accused is given all the opportunity to lead a normal life and even threaten the victim again.

“The accused try to mislead the case, sometimes with the help of the cops. People are more aware now but the conditions are the same in the suburbs. They do not know that there are two sections under IPC which can give them succour,” said Chaudhari. “The accused joins with the police and is shown as absconding in police reports, whereas the victim keeps getting threats from him to withdraw the case.”

It is high time India learns from Bangladesh (see box) and frames more elaborate laws for acid attacks. Bangladesh also has provisions for capital punishment in such cases. In India, the only known case where the accused was awarded the death penalty was that of Preeti Rathi, a 23-year-old nurse who was attacked by Ankur Panwar, 25, at Bandra Terminus in May 2013. Rathi succumbed to her injuries a month later. The accused had attacked her because she had rejected his marriage proposal. In a landmark judgment, the trial court sentenced him to death. However, as it was a trial court judgment, it can be challenged in a higher court.

Even after enacting a law, justice continues to evade acid attack victims in India.