Can India and Pakistan be fair to suspects of espionage and terrorism from the other country?

~By Parsa Venkateshwar Rao Jr

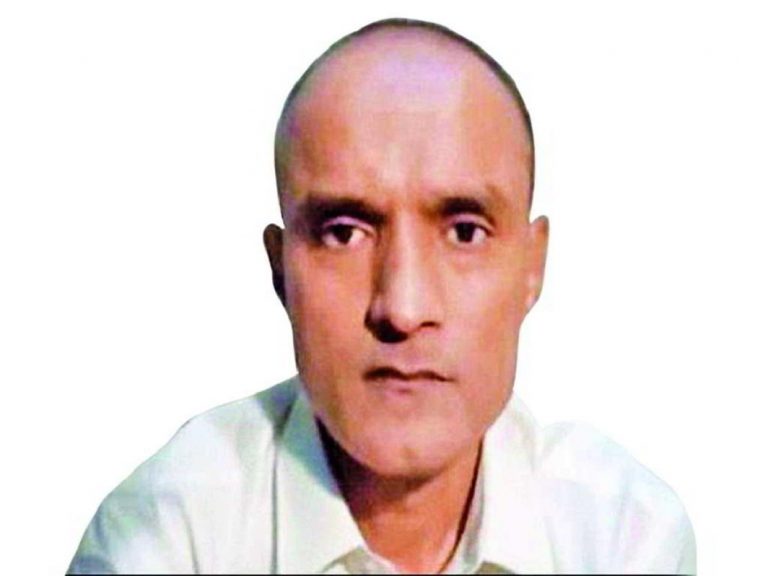

The basis of India’s argument in the case of Kulbhushan Sudhir Jadhav, an Indian national sentenced to death by a Pakistan military court, at the International Court of Justice at The Hague is the denial of consular access to him, and only secondarily, his human rights. This highlights the basic fact that in international law, it is the states that are the main protagonists and the individual is not yet recognised as a legitimate subject. Scholars in international law are arguing that it is time to recognise the individual as the key actor in such cases. Before we look at some of the arguments that place the individual at the centre of international law, it would be helpful to look at the Indian argument in the Jadhav case.

India has invoked Article 36, paragraph 1 (b) of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, 1963, (acceded to by India on November 28, 1977, and by Pakistan on April 14, 1969) called “Communication and contact with individuals of the sending State”. It says:

- With a view to facilitating the exercise of consular functions relating to nationals of the sending State:

….(b) if he so requests, the competent authorities of the receiving State shall, without delay, inform the consular post of the sending State, within its consular district, a national of that state is arrested or committed to prison or to custody pending trial or is detained in any other manner. Any communication addressed to the consular post by the person arrested, in prison, custody or detention shall be forwarded by the said authorities without delay. The said authorities shall inform the person concerned without delay of his rights under this subparagraph.”

India’s argument was that Pakistan had arrested Jadhav on March 3, 2016 —it had alleged that he was kidnapped from Iran and was shown to have been arrested in Balochistan—but it (Pakistan) had notified the Indian authorities only on March 25, 2016. India had requested for consular access on the same day. India said that on January 23, 2017, Pakistan had requested assistance in the investigation against Jadhav with regard to “involvement in espionage and terrorist activities in Pakistan”, and through a Note Verbale of March 21, 2017, made access to Jadhav conditional on India’s assistance in the investigation.

Right now, Pakistan reserves the right to try Jadhav in its own jurisdiction. To prove that its judicial system is fair, it may have to allow third-party observers.

India argued that this in itself was in violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations.

India had also invoked the basic rights of Jadhav under the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, especially Article 14, which mandates a fair trial and all that goes with it, including the right to appeal and proper legal assistance. But the basic rights of Jadhav were not the basis of the Indian argument. That is an argument which has to be made by Jadhav’s lawyer.

India is invoking the Vienna Convention and the denial of consular access to the prisoner guaranteed by it as the reason for “provisional measures” until the Court meets to hear the case in full. The International Court had granted India’s request on May 10.

Now we get back to the argument that is sought to be made here: the position of the individual in international law. Scholars on the subject have pointed out that traditionally, international law meant law that governed the relations of sovereign states.

They added that after the Second World War, especially the Nuremberg Trials, and the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, an individual’s rights have been brought centre-stage in international law.

But those who argue in favour of the individual in international law are well aware that his/her position is not firmly established here. Many of them blame the positivists of the 19th century, especially British Utilitarian thinker Jeremy Bentham and his followers, who were emphatic that international law should deal only with sovereign states.

Those favouring individuals in international law blame 19th century thinkers like Jeremy Bentham, who emphasised that international law should deal only with sovereign states.

And critics of positivism point to the great 18th century British legal authority of common laws, William Blackstone, who understood international law to be the law of nations, and which included individuals. It is also shown that the United States Supreme Court had accepted individual rights to be an integral part of international law.

As things stand today, there is greater recognition of individual rights when they are violated by tyrannical arguments at home. The international tribunals which tried the cases of genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda provide a good example on this.

The question that arises in the case of Jadhav, and many others in his position, is whether they can defend themselves before an international court when they are put in the dock by a hostile country. For example, is it obligatory on the part of Pakistan to arraign Jadhav, accused of espionage and terrorism, in an international legal forum? Right now, Pakistan reserves the right to try Jadhav in its own jurisdiction and through its own judicial system. To prove that its judicial system is fair, it may have to allow third-party observers. Of course, no sovereign state would accept this conditionality.

In the case of Jadhav, Pakistan’s conduct has been far from objective and fair. There should have been a possible appeal to an international court. But Jadhav cannot do so. And India can do so only in asserting its rights to consular access, but it cannot question the fairness of the proceedings of a Pakistan court.

Citizens of hostile countries accused of espionage and terrorism need a fair trial. Alleged Islamic terrorists in the US need it, as well as Indians in Pakistan and Pakistanis in India. Is there a need for an international court system to deal with such cases? In effect, international law needs to be updated. It is not going to be easy. Nation-states are not going to surrender their sovereign rights. One way out of the dilemma is for host countries to provide an exemplary judicial process.

To a great extent, American courts have thrown out all the charges against an overwhelming majority of the prisoners in Guantanamo Bay prison on charges of terrorism. The credibility of Pakistan’s judicial system, or that of India’s will depend on when they would throw out a case against a foreigner for lack of evidence. That is a tough test at the best of times for both India and Pakistan.