To keep both the Malays and non-Malays happy, PM Mahathir bin Mohamad has allowed the controversial Islamic preacher Zakir Naik to stay in the country but with an unannounced gag order

By Asif Ullah Khan

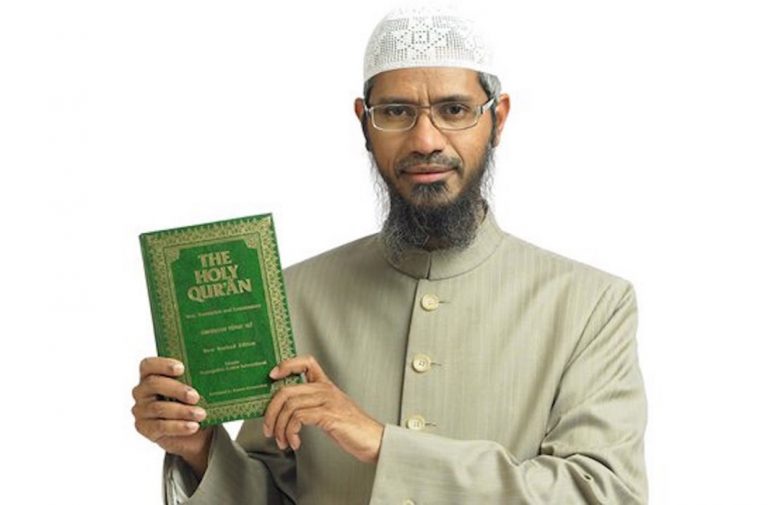

In 1970, Dr Mahathir bin Mohamad wrote a controversial book, The Malay Dilemma. As prime minister of Malaysia for the second time at the ripe age of 93, he faces another dilemma—how to deal with the presence of fugitive controversial Islamic preacher Zakir Naik in his country. In fact, Naik has become a Hafiz Saeed of sorts for Malaysia.

His presence has frayed racial tensions and is posing a headache for the new Malaysian government. It cannot deport him because of his popularity among the Malay Muslims but, at the same time, wants to keep a check on his controversial sermons as they threaten to rip apart the multi-racial fabric of Malaysian society.

Unlike India, where he faces terror and money-laundering charges, the hardline Islamic preacher is a popular figure in Malaysia where more than 60 percent of the population is Muslim. This is the reason why both Mahathir and his predecessor, Najib Razak, refused to deport him to India because it could be interpreted by hardline Muslim organisations as “anti-Islam”. Murmurs against Naik started in 2016 when it emerged that two of the militants who had stormed into an upmarket café in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing 22 people, were “inspired by his preaching about Islam”. At that time, the Barisan Nasional (National Front) government led by Razak was in power. The Barisan Nasional coalition comprises three major ethnic political parties—United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), and Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). For the first time in the history of Malaysia, the MCA and MIC questioned their government’s continued support to Naik as they felt that his presence in Malaysia was detrimental to society.

The then health minister in the Razak government and MIC president, S Subramaniam, was the first one to express his disagreement with Naik’s stay in Malaysia and said that his activities “are outside the Malaysian context”. “I don’t think Malaysia needs Zakir Naik. Is he going to contribute to the advancement of Islam in the country? The answer is no,” said Subramaniam.

The issue took a serious turn when a group of 19 human rights activists filed a civil suit against the Malaysian government in March 2017, accusing it of failing to protect the country from the controversial televangelist. The suit, among others, sought a government declaration that Naik was a threat to national security, called for a ban to prevent him from entering the country, and sought his arrest and deportation immediately. The group, comprising different religious and ethnic backgrounds, said that Naik was an “undesirable person” and “a preacher of hate” who was currently roaming free in Malaysia.

Soon rumours started doing the rounds that the reason why the Razak government was taking no action against Naik was because it had already granted him Malaysian nationality. Finally, on April 18, 2017, then Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid Hamidi clarified the government’s position, saying that Naik had not been granted citizenship but admitted that he was granted permanent resident (PR) status about five years earlier when Hamidi was not the home minister.

The Chinese coalition partner of the then Razak government, Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), questioned the granting of PR status to Naik. The MCA’s religious harmony bureau chairman, Datuk Seri Ti Lian Ker, said the government should not risk the country’s spirit of mutual understanding and respect. “The government, especially the home ministry, must also account as to why Zakir was granted PR status and special consideration, seeing that he is known for creating tension,” he said.

This led Naik’s supporters to mount a counter-offensive. The first one to come to his rescue was PAS (Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party), which made it into an “us” versus “them” issue. PAS information chief Nasrudin Hassan, hitting out at Subramaniam said Naik was a renowned scholar, respected by Muslim clerics and the Muslim world as a whole. He then “advised” Subramaniam not to go overboard with his statements, especially related to the interests of the Muslims in the country, and added that being a health minister, he should not interfere in this matter.

Another right-wing group, Perkasa or Pertubuhan Pribumi Perkasa (Malay for “Mighty Native Organisation”), which honoured Naik with an award for his contributions to the struggle for Islam, also jumped into the fray and took offence to Subramaniam, a Hindu, interfering in Muslim affairs. Perkasa president Datuk Ibrahim Ali said that Subramaniam should resign from the Razak cabinet if he could not agree with the government’s decision to grant PR status to Naik. Perkasa even told its members to campaign against Subramaniam and other MIC candidates in the general election.

However, things changed completely when Malaysia’s landmark 2018 general election brought the 93-year-old Mahathir back to power in his new avatar as the head of the Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan), which comprises mostly multi-racial, secular and centre-left parties. Since then, Naik has been lying low. He lives in a condominium in Putrajaya, the administrative capital of Malaysia, and is only seen during Friday prayers. He had made repeated attempts to meet Mahathir and even jostled with the crowd to greet him when the latter came to Putrajaya mosque to offer prayers. And finally, when he met Mahathir last July, he thanked the new government for not deporting him to India and vowed that he would abide by all laws of the country.

Mahathir, on his part, said that as long as Naik was not “creating any problems” in Malaysia, he would not be deported. But the prime minister has tactfully banned his public lectures and appearances, although the official government version denies that there is any ban on Naik’s lectures. All his attempts to appear in public have been nipped in the bud on the basis of “technical grounds”.

Recently, an Islamic NGO called the Islamic Propagation Society International (IPSI) had sought permission to use the city stadium in the Malaysian state of Penang for Naik’s lecture but the Penang Island City Council refused the permission on “technical grounds”. Its community service director, Rashidah Jalaludin, in a letter dated February 13, said that IPSI’s request “could not be considered” as the city stadium had been recently upgraded and was being used for sports. Perhaps the venue was not suitable for the “ceramah” (lecture), the official added.

Interestingly, Penang Deputy Chief Minister Ramasamy Palanisamy, a member of the Democratic Action Party (DAP), a coalition partner of Pakatan Harapan, has on numerous occasions questioned the government’s decision not to extradite Naik to India.

In April 2015, Ramasamy called Naik “Satan” and accused him of making speeches “designed to promote hatred of other faiths”. He urged, via Facebook, “peace-loving Malaysians” to lodge police reports against Naik so that he can be banned from entering the country. “Let us get ‘Satan’ Zakir Naik out of this country! He is a Muslim preacher and evangelist who has nothing but hatred and contempt for non-Muslims,” wrote Ramasamy.

“He has been banned in Canada and UK (United Kingdom) for his hate lectures. Even some sections of the Muslims in India have termed him a liar, man of half-truth and purveyor of hate,” Ramasamy wrote.

However, this did not go down well with the Malay Muslims. Not only did he face an “online onslaught”, even his office in Penang was bombed with a petrol explosive.

The question is: Can Malaysia afford to defend such a polarising figure at a time when a very mellowed Mahathir heads a coalition government which comprises multi-ethnic, secular parties? Many Malaysian commentators say Naik has become a national dilemma as his presence continues to cause uneasiness and discomfort in the multi-religious and multiracial community.

They say that although Naik talks about propagating Islam and social harmony, there is a distinct waft of cultural and religious imperialism in his recorded comments. Among them is the infamous statement to the effect that an Islamic country should not allow churches to be built because Christianity is a religion that is “wrong”. Christianity is practised by more than nine percent of the Malaysian population and there are five Christian ministers in the Mahathir cabinet.

Is Naik worth the rift he is causing in Malaysian society? The reasonable answer will be a big “No”. But to keep both the Malays and non-Malays happy, Mahathir has allowed Naik to stay in Malaysia and at the same time has tightened his leash over him by imposing an unannounced gag order.

—The writer is a former deputy managing editor of The Brunei Times