Despite the constitution having enough safeguards against persecuting practitioners of this philosophy, the murders of H Farook, MM Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare show that the perpetrators usually go scot-free

~By Sucheta Dasgupta

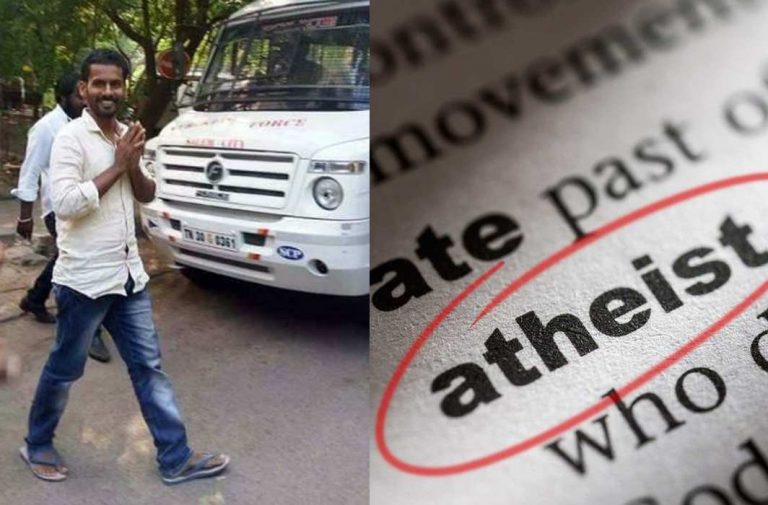

On the morning of March 16, 31-year-old scrap dealer and atheist H Farook received a phone call, started his two-wheeler and left home. That was his last trip. He had been receiving threats over the past few weeks for running a 400-strong WhatsApp group that discussed the ways and thinkings of legendary social activist EV Ramasamy Periyar. He was asked to close the group, but had refused.

That day, Farook was waylaid by a gang of four who stabbed him in the stomach and neck. His lifeless body was found near the Coimbatore Corporation’s sewage farm. On March 17, Podanur Sriram Nagar resident M Arshad surrendered to the police, claiming responsibility for Farook’s murder. Coimbatore DCP S Saravanan told the media that Farook, a Dravidar Viduthalai Kazhagam member, had angered the Muslim community by voicing his rationalist opinions on social media.

Farook’s murder is the latest in a series of murders of rationalists in South and West India in the last 3-4 years. These included those of MM Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare. Even Bangladesh, our neighbor, has had instances of such killings, while in 2015 in Karachi, social worker and rights activist Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead for similar reasons.

Supreme Court advocate and Human Rights Law Network director Colin Gonsalves said that Farook’s death, apart from being a murder punishable under Section 300, is also a breach of several Fundamental Rights. These include Articles 19(1)(a) dealing with freedom of speech and expression, 19(1)(c) on freedom to form associations and unions, 21 (right to life or protection of life and personal liberty), 25 (freedom of conscience and free profession, practice and propagation of religion) and 28 (freedom as to attendance at religious instruction or religious worship in certain educational institutions).

“This is pure and simple fascism. This is how Hitler in Germany, Mussolini in Italy and Franco in Spain came to power—on the basis of intimidation of people. The government has done nothing to protect constitutional freedoms. People are persecuted for exercising their rights. Fifteen RTI activists died before the law was passed. Why has the police not done its job? Fanaticism across the religious divide must be condemned,” Gonsalves stressed.

Does India need a constitutional amendment to include the freedom of irreligion as a fundamental right or any other law to officially recognise atheism given the spate of killings of atheists in recent times?

Courts have given divergent judgments regarding religious freedoms. In the Stanislaus vs State of Madhya Pradesh case, Reverend Stanislaus of Raipur had challenged the Madhya Pradesh Dharma Swatantrya Adhinyam Act which prohibits the use of “force, fraud, or allurement” for religious conversions. But the Madhya Pradesh High Court in 1977 upheld this Act. However, when the Orissa Freedom of Religion Act was challenged in the Orissa High Court, the Court held that the definition of “inducement” was too broad and ruled against the Act. However, the Supreme Court heard both these cases together and ruled in favour of the Acts.

It is to be noted that Farook had not resorted to any force, fraud or allurement to propagate his views. He was also not engaged in any act that was against public order, morality and health, which are the safeguards against the unbridled exercise of Article 25.

Farook’s death also highlights the importance of his activism in the context of the faith he was born into. There is no room for the atheist philosophy in the three Abrahamic religions—Islam, Christianity and Judaism. This opens up the question: Does India need a constitutional amendment to include the freedom of irreligion as a fundamental right or any other law to officially recognise atheism given the spate of killings of atheists in recent times?

Both Gonsalves and senior advocate ND Pancholi disagreed. Pancholi said that the freedom of irreligion is “built into Article 19 as the freedom of thought and the freedom to believe or not believe any religion”. “There is no harm trying. The parliament is unlikely to pass it for this reason, but it would lead to discussion on the need to recognise atheism as a philosophy. This will indirectly influence public perception and behaviour towards atheists,” he said. Gonsalves interpreted atheism as a part of Article 25—freedom of religion.

Incidentally, according to the 2011 Census, about 29 lakh people, or 0.24 percent of its 1.25 billion population, are categorised under “religion not stated”. Of them, 33,000 identified themselves as atheists, according to the Census.

On March 10, MP Shashi Tharoor had even introduced the Anti-Discrimination and Equality Bill 2016, a Private Members’ Bill, in the Lok Sabha. This was meant to ensure equality before law for all citizens so as to protect their personal liberty and address various injustices.

Pancholi said that the fact that it is a Private Member’s Bill shows that the government is not interested in protecting the rights of its people. He said that under Article 51(a) which lists some Fundamental Duties, the people of India, “which automatically implies the government, too, must develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”. “If the cultural environment in our country is not improved, such incidents are bound to take place,” Pancholi said.

Another topic of debate is whether a Muslim can be an atheist. Does that give rise to conflict? Is that a moral paradox? Not so, believes All India Muslim Personal Law Board executive committee member Kamal Faruqui.

“Whatever school of thought a person belongs to, killing him for that reason is not only to be condemned but is a serious humanitarian issue. The Quran clearly says, ‘Unto you your religion, unto me mine.’ There is another surah which says: ‘There shall be no compulsion in the religion. The right course has become clear from the wrong.’ So it is up to the individual to believe in the faith. If he does good things, he will surely be rewarded.”

Religion or the lack of it is clearly an issue which grips people in India.