The famous Kake-Da-Hotel has filed a case against Kaka-Ka Dhaba Pvt Ltd in Delhi High Court for infringing on its trademark. Is “Kaka” too generic a name and can monopoly be claimed over it?

By Vrinda Agarwal

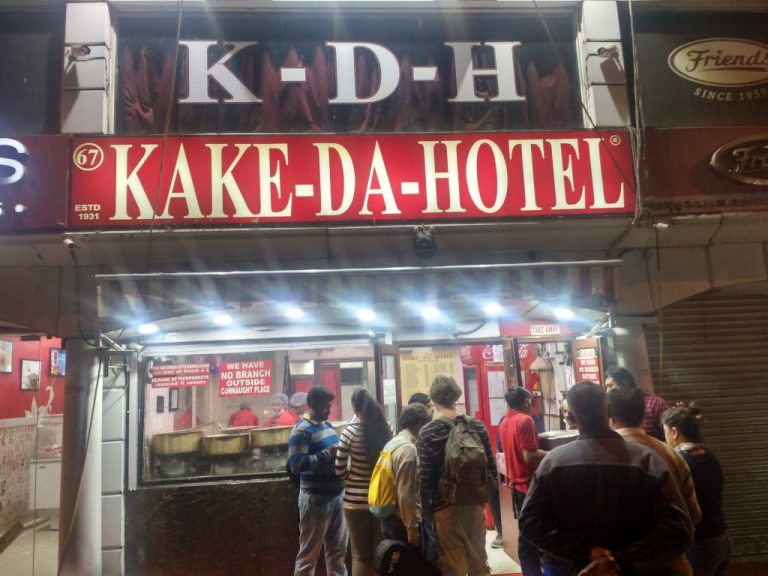

What’s in a name? Ask this question to the owner of the famed Kake-Da-Hotel in Connaught Place, New Delhi, and he would have much to say about it. After all, he went to court over the name of his eatery being used by another entity. Nothing savoury here for sure.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “Kaka” means a large New Zealand parrot, brownish in colour and often kept as a pet. Closer home, the word boasts of Punjabi origins and means a baby. Its original meaning aside, the word seems to occupy a prominent place in the food business, as Kake-Da-Hotel went ahead and sued Kaka-Ka Dhaba Pvt Ltd for trademark infringement.

The former alleged that the latter’s trademark sounded deceptively similar to its own. After protracted litigation spanning over four years, the case is up for final adjudication before the Delhi High Court. The court battle is being fought to determine whether the words “Kaka” or “Kake” can be monopolised by any one party and given trademark protection.

The plaintiff, Delhi’s iconic food outlet, Kake-Da-Hotel, contended that it adopted its trademark in 1931 when it started operating a restaurant in Lahore, Pakistan. Post-Partition, its founder shifted to Delhi and opened a restaurant by the same name at Connaught Place. It further contended that the name “Kake-Da-Hotel” had acquired enormous goodwill and reputation, and the earliest trademark registration dates back to December 14, 1950. It also claimed to have registered the trademarks “K-D-H Kaku-Da-Hotel” and “K-D-H Kake-Da-Hotel” in its name.

However, the defendant said that although it had adopted the trademark “Kaka-Ka Dhaba” in 1997, the family has been operating a food cart by this name since the early 1980s, and its three outlets in Nashik—Kaka-Ka Dhaba, Kaka-Ka Hotel and Kaka-Ka Garden—were started 17 years ago. The Nashik-based company’s defence hinges on the legal argument that the word “Kaka” is generic and no monopoly can be claimed over it.

For now, Justice Pratibha M Singh of the Delhi High Court has passed an interim order, directing the defendant to inter alia refrain from opening any new outlet with the name “Kaka-Ka” during the pendency of the suit. The defendant has also been directed to maintain complete accounts of all sales in its three restaurants/outlets. Whether or not the Delhi High Court will accept the generic argument will be known only on December 20, the next date of hearing.

However, this case has brought into focus one of the most keenly contested aspects of trademark law—that a trademark, in order to qualify for registration, should be sufficiently distinctive and not generic. The Trademarks Act, 1999, defines a trademark as “a mark capable of being represented graphically and which is capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one person from those of others and may include shape of goods, their packaging and combination of colours”. The definition, although broad, is qualified by another provision in the Act which allows for registration of only those marks that are sufficiently distinctive in nature.

The distinctiveness requirement has been a subject of legal disputes on multiple occasions, especially when manufacturers have sought to use common or generic words in their trademarks.

In July 2018, the Supreme Court dealt with this issue in Nandhini Deluxe vs Karnataka Co-Operative Milk Producers Federation Ltd. The respondent company, which sold milk and milk products under the name of “Nandini” had argued before the Karnataka High Court that the appellant had infringed upon its trademark by using the deceptively similar name of “Nandhini” for its chain of restaurants. The High Court had ruled in favour of the respondent.

When the matter was taken in appeal before the Supreme Court, it set aside the High Court’s order and ruled in the appellant’s favour, saying that although the words “Nandhini” and “Nandini” were phonetically similar, “a bare perusal of the two trademarks would show that there is hardly any similarity of the appellant’s trademark with that of the respondent when these trademarks are seen in totality”. The Court further observed that: “Nandhini/Nandini is a generic name, representing a goddess and a cow in Hindu mythology, and it is not an invented or coined word of the respondent”.

In December 2013, a similar issue arose before the Madras High Court in AD Padmasingh Isaac and M/s Aachi Masala Foods (P) Ltd vs Aachi Cargo Channels Private Limited. This case involved the use of the word “Aachi” by both appellant (a masala company) and respondent (a cargo company). While dismissing the infringement suit filed by the appellant, the Madras High Court observed that the word “Aachi”, which means grandmother in Tamil, is “of general use”, and cannot be the monopoly of any one party.

A similar issue came up before the Delhi High Court in 2011, in Bhole Baba Milk Food Industries Ltd vs Parul Food Specialities (P) Ltd. In this case, the High Court had to adjudicate on whether the word “Krishna” could be monopolised by any one party, as the appellant and the respondent sold dairy products under the names “Krishna” and “Parul’s Lord Krishna”, respectively. While dismissing the appellant’s suit, the Delhi High Court observed that the word “Krishna” was of common origin, and thus it could not give exclusive statutory right to the appellant with respect to the use of the word. The Court further said that the appellant could only claim distinctiveness, if at all, in the way the word was written in its trademark.

It will be interesting to see if the Delhi High Court follows its earlier precedent and that of the Supreme Court and the Madras High Court while deciding whether “Kaka” and “Kake” can be used exclusively by any one party in its trademark.