Revolutionaries, agitators and their collaborators are the real patriots. Let us not use British era laws to curb them. Instead, their struggles and ideologies must be studied for valour and fortitude.

By Justice (retd) Kamaljit Singh Garewal

The cynical view of a rebel, living in remote rural or forest communities, could well be uninformed because he has remained untouched by the gigantic strides India has made in every field. So he can be forgiven if he feels that the majority of the citizens of India are humble, meek and voiceless, like him, and make no demands. The rebel may feel that if the citizens are hungry, they don’t ask to be fed. They meekly accept what the State, run by one party or a coalition of parties, feeds them through its various schemes. The same is true with regard to schemes for housing, education and health. The only expectation from citizens is that they must vote for one or the other party, every five years at election time. According to the rebel, this in a nutshell is our Republic, 70 years on.

If this is really how things are, the choice before citizens is to accept the laws and abide by them or lodge their protest and dissent and disobey what they feel is unfair and unjust. Has anyone ever wondered why the main reason for so much dissent is the way governments have been running so far? Dissenters ask for things to change. And when change doesn’t come, the next course for the impatient dissenter is to rebel.

So a rebel, a dissenter, or a conscientious objector is simply someone who wants to put forward a certain point of view. The law abiding, do gooder, committed to the rule of law finds this objectionable. It’s a meaningful debate which should be allowed to go on and not stifled. It’s not for the citizens to judge what to do with the rebels. We have the courts to punish law-breaking rebels. But let’s not use British era laws to curb the argumentative rebel. Laws need not be static, they must be made more liberal, if society is to change and urgent reforms introduced.

While defining fairness and justice, the often cited example is of children who possess a very acute sense of justice and fairness. To illustrate this point, take the case of a school going boy who gets two chocolates for doing well, while his younger brother, still a toddler, gets one. Immediately, the toddler will raise a hue and cry for being unfairly treated. Every child while growing up sees injustice at home, at school, at university, if he gets that far, but learns to accept it because mostly things are reasonable and fair. But future rebels also rise from our children. A child not pacified or consoled may grow to be a rebel and protest every unfairness he sees later in life. There is nothing wrong with this if the protest is kept within limits.

The rebel is a citizen as anyone else, maybe even better in some ways because he protests against unfairness and injustice. He may have a different point of view, and as a good citizen, seek peaceful change or reform. But people who are threatened by change can always find a battalion of so called good citizens to take it upon themselves to block the rebel from pursuing his cause. And if some archaic law is broken, the rebel gets hauled up and offences of sedition, slander, defamation and libel are pressed into service, while the cause celebre is forgotten.

We don’t seem to remember our famous patriots, who proudly embraced the gallows. They would have guffawed if they learnt that, 70 years on, free speech was controlled by Raj era laws and offences like sedition and defamation were still extant. They must have committed all these petty offences, many times over, during the build-up of their revolutionary movements, before picking up arms and using them against the servants of the Raj. According to the authorities, they were terrorists who believed in violent protests. And even our non-violent independence movement felt the same way. But the time has come to celebrate their lives for their valour, determination and idealism. These rebels terrorists martyrs were first class patriots. We only recognise non-violent freedom fighters, but have no time for our rebels, our true patriots.

Madan Lal Dhingra of Amritsar was hanged in London on July 1, 1909, for killing Curzon Wyllie, who also happened to be a close friend of his father. Dhingra had been sent to London by his father who was the civil surgeon of Amritsar to study engineering at University College, London, after he was expelled from Government College, Lahore, for disobedience. On arrival, he became a part of VD Savarkar’s group, which also conspired to simultaneously kill a magistrate, a pious Sanskrit scholar, in Nashik. Dhingra was caught at the spot, tried, undefended at the trial, but made a stirring speech justifying his act.

Savarkar’s part in the magistrate’s killing was to send 20 pistols to India, out of which one was used in the crime. When Savarkar came to know that the British police was on the lookout for him, he escaped to France to be harboured by the founder of the Free India Society, Madame Bhikaji Cama, in Paris. He was arrested and brought back to England and then sent to India to face trial. On the way, the ship docked at Marseilles and Savarkar jumped off the ship to meet a friend who was to pick him up in a car. He swam ashore, but his friend was late, so he got nabbed, was tried and sentenced to 20 years, which he served at the infamous Cellular Jail in the Andamans.

At about this time, Kartar Singh Sarabha of Ludhiana was studying at Ravenshaw College, Cuttack. One of his famous contemporaries was Subhas Chandra Bose, but there is nothing to suggest that the two knew each other. He left without completing his studies and was sent to Berkeley University in San Francisco. But instead of studying, he joined the newly formed Gadar Party set up by Sohan Singh Bhakna of Amritsar and Lala Hardayal of Delhi. Singh also learnt to shoot, make bombs and fly. They planned to smuggle weapons to Punjab to start an armed revolution. He sailed from America, reached Lahore with the consignment of firearms, met Rash Behari Bose, the main planner. For some reason, the date of the rebellion was advanced by a few days and the authorities got wind of it. It is said that there was an informer among them. Singh was arrested, along with Vishnu Pingle, tried and both were hanged on November 16, 1915, while Rash Behari Bose managed to escape. This handsome young man was just 19. Sohan Singh Bhakna was also sentenced to death, which was commuted to life. He was released after 16 years and lived to a ripe old age. Such dauntless bravery, such courage, such patriotism. The Gadar movement produced many patriots.

When in April 1919 the devastating massacre took place in Amritsar, a young orphan from Sunam was there helping the injured. His name was Udham Singh, the patient assassin of Michael O’Dwyer, the lieutenant governor of Punjab who was responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1919 and whom he shot dead in London on March 13, 1940, in revenge. Udham Singh was hanged after a few months in London.

Coming to the life of Shaheed-e-Azam Bhagat Singh, one sees the confluence of many streams of revolutionary ideas. He was born in Khatkar Kalan, Punjab, in 1907. By then, his uncle Ajit Singh (26) and future mentor Lala Lajpat Rai (42) had already been sent to Mandalay in Burma. Their offence was espousing the cause of agrarian reform and agitating against the Punjab Colonisation Act. After two years, they were released and returned to India. Bhagat Singh must, no doubt, have been influenced by his uncle Ajit Singh, but more so by Lala Lajpat Rai, and his National College, Lahore, where he was to later enrol. At the college, Bhagat Singh immersed himself in revolutionary literature and became an admirer of Kartar Singh Sarabha. He also joined the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA). He must have been swayed by Lala Lajpat Rai, who himself had written books on the Italian patriots, Garibaldi and Mazzini. Ajit Singh had left India in 1910, but returned only in 1947, and died on August 15, 1947 at Dalhousie. What an auspicious day to die, when life’s work is done.

Returning to Bhagat Singh’s life, a major event took place. On October 30, 1928, Lala Lajpat Rai was leading an agitation against the Simon Commission at Lahore railway station. The agitators were baton-charged, a blow fell on Lalaji’s head and he succumbed to his injuries on November 17, 1928. Bhagat Singh and his compatriots of HSRA planned to kill Scott, the police officer who had hit Lala Lajpat Rai, in revenge. Exactly after a month on December 17, Bhagat Singh and others shot John Saunders, a British police officer, dead, mistaking him to be Scott.

Bhagat Singh was not one to give up his revolutionary activity. He organised and planned a dramatic way to bring attention upon himself and his comrade Batukeshwar Dutt. He tossed a harmless little bomb in the Central Assembly on April 8, 1929. And then, raising the cry “Inquilab Zindabad”, he threw leaflets in the hall. When he was arrested, a photograph of his hero, Kartar Singh Sarabha, was recovered from his pocket. He was also charged with the earlier killing of Scott in Lahore. In an absolutely illegal and unfair trial where he was denied a defence counsel, denied an opportunity to cross examine approvers and denied an appeal, Bhagat Singh was convicted and sentenced to death. Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and Shivaram Rajguru were hanged on March 23, 1931.

Mahatma Gandhi had just concluded the Irwin-Gandhi pact on March 5, 1931. It was a momentous agreement. A few days before the date of hanging, the Mahatma met Lord Irwin and sought commutation of Bhagat Singh’s death sentence. The Viceroy declined, at which the Mahatma pleaded that if Bhagat Singh was hanged on March 24, on the opening day of the Congress Session at Karachi, there would be commotion and the benefits of the recently concluded pact may be drowned. It is said that the Mahatma then asked the Viceroy to advance the date of the execution by a day. Those days, Jawaharlal Nehru was the rising star of the Congress party and must have been in the midst of these developments. But Nehru never showed any solidarity with Bhagat Singh and other rebels, who had caught the imagination of the youth of India. There is no mention of the contribution of any rebel in Nehru’s personal memoir and manifesto, The Discovery of India, published in 1946.

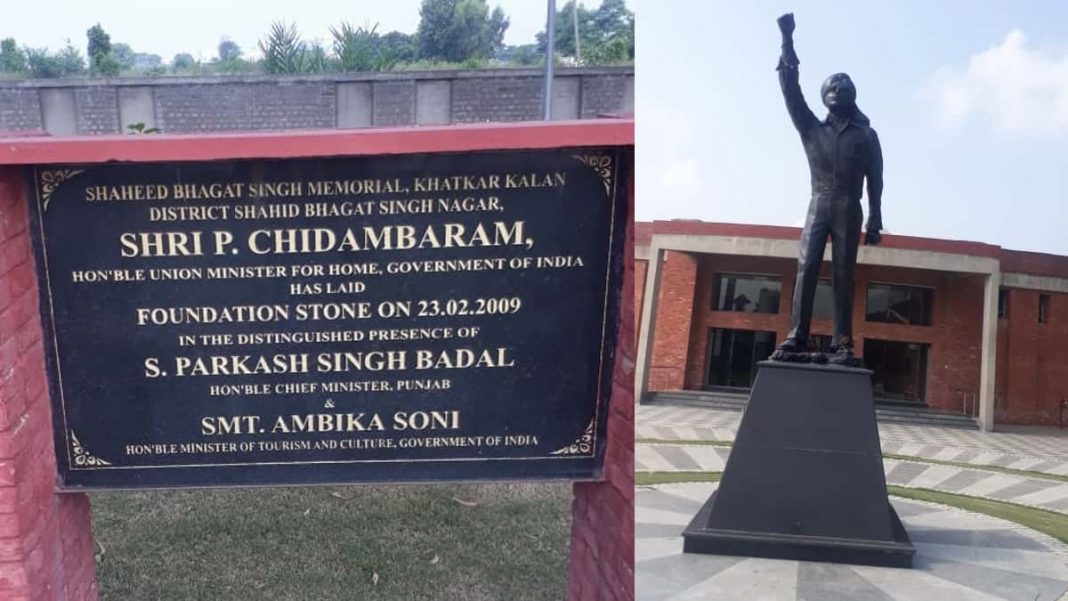

Rebels, revolutionaries, agitators and thousands of their collaborators are the real patriots. Their lives, struggles, ideologies must be studied for guidance and inspiration for they are examples of bravery, steadfastness, honesty, integrity and fortitude. Instead, we see a plaque outside Bhagat Singh Memorial in Khatkar Kalan displaying the names of politicians in very prominent letters, obscuring the name of the Shaheed-e-Azam. We have forgotten our true patriots.

—The writer is former judge, Punjab & Haryana High Court, Chandigarh and former judge, United Nations Appeals Tribunal, New York