By Sujit Bhar

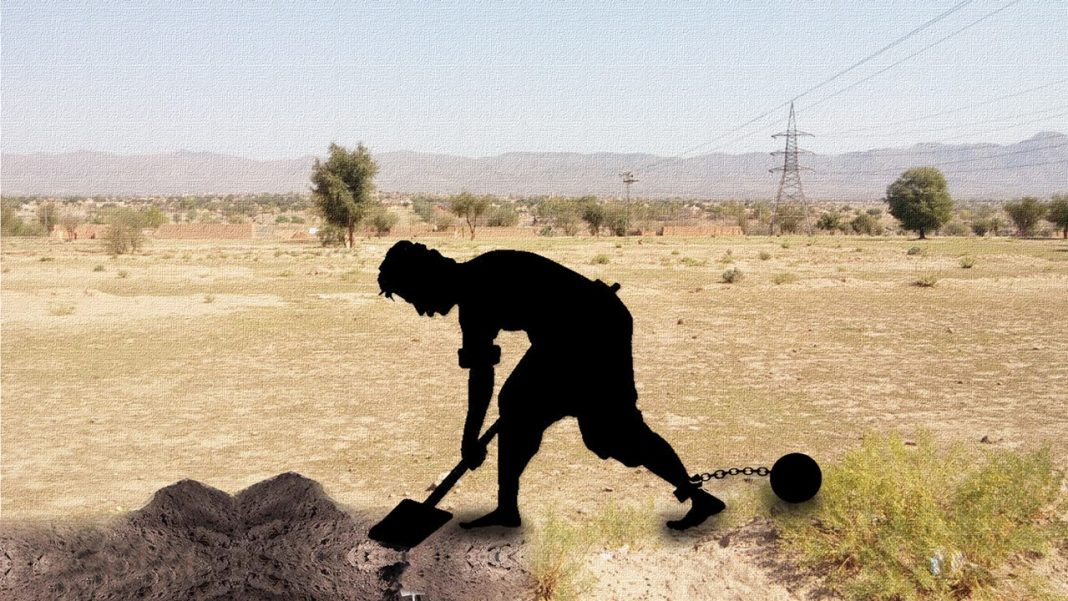

Bonded labour is not just an Indian problem; it exists across the world across seamless boundaries, from so-called liberal democracies to autocracies, from sub-Saharan Africa to Southeast Asia. And, of course, in India the problem persists, despite laws having been written as far back as 1976, when the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act was passed.

Why has this horrible practice, akin to modern day slavery, persisted? Last we checked, post Independence India has never been an autocracy. Why cannot we find these hapless people, get them out of the clutches of evil, reinstate them in a wholesome life and punish the criminals? The basic reason is easy and complicated at the same time.

To understand the phenomenon, let us look into another aspect of India’s shaky justice system. News of rape victims, of people being hunted down for their beliefs running to local police stations, yet not being able to lodge First Information Reports (FIR) is common. Why does this happen?

Sometime back, a retired senior police officer had explained why police stations hesitate and often point blank refuse to take FIRs on criminal acts that need immediate attention. The “performance” of each thana and its SHO is reviewed by the respective SPs once a quarter. More FIRs would mean the thana chief, or the SHO, was not being able to control his area and crimes are growing. This would be the inference of the quarterly report and the SHO’s promotions would be hindered, maybe he will be transferred to a not so desirable location.

Think about it for a moment: a rape victim cannot have an FIR lodged at the police station, just because the SHO’s career has to be protected. Of course, there are other reasons as well, such as the political affiliation and influence of the rapist.

The issue of bonded labour reporting is mired in as much chicanery. Elections today are a dime a dozen, some politician or the other facing the public for a mandate almost every part of the year. If the state government—the state governments are the ones required to do reporting on the status of bonded labour in the state—provides realistic pictures, the image of the ruling party will be tarnished and the Opposition will use this information to target the government.

That means those in bondage remain in bondage, just so the ruling party can show a clean, efficient image to the electorate. For all practical purposes, the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act is probably one of the least used acts. India’s mission to eradicate bonded labour by 2030 will, most certainly, remain a pipe dream. The objective was announced in Parliament by the Union government in 2016. “Total abolition of bonded labour” was supposed to be the government’s 15-year vision and it was also announced that the government intends to identify, release and rehabilitate around 18.4 million bonded labourers by 2030.

IndiaSpend, a fact-based organisation that looks into social issues, has delved into available data and come up with amazing figures that show how vain the government’s intentions have proven to be. According to it, quoting Union, government data, 3,15,302 people were released from bonded labour in over four decades between 1978 and January 2023, of which 94% have been rehabilitated.

If that data is the base rate, then “the government, since its statement in 2016, has been able to release only 32,873 people from bonded labour, a yearly average of 4,696.” IndiaSpend averages this at the same annual rate and arrives at a 2030 figure which is just 2% of its 18.4 million target.” That still leaves 18 million Indians in bonded labour.

Two obvious reasons

Tomes of data can be referred to, creating another tome of a report that will also end up gathering dust in some corner of some government department. The overall mystery, it seems stems from two facts, except for the obvious one, that there are evil people in this world. The first is that governments do not even want to address this contentious issue, and just like the SHO of the thana, refuses to admit that bondage remains a modern problem. No amount of detergent will wash away the associated guilt and this cannot happen to netas in white.

The second reason is the crumbling and often corrupt justice system of the country. Forget the high and mighty courts: these meek people, chained to disastrous fate, won’t even get past their local police outposts if they dare to complain. And then there is the SHO problem. Why can’t the people just work quietly? Why must the status quo be disturbed; why must the officer pay with his career for one bold slave?

The Act actually empowers the district magistrates and sub-divisional magistrates to take direct action, keeping the SHO completely out of the picture. The district magistrate has to give a certificate of bondage, which starts the process of rehabilitation. Since 1978, a centrally-funded scheme had allotted Rs 4,000 for each worker, which has now been enhanced to Rs 20,000. In February 2022, further immediate financial support of Rs 30,000 to the rescued labourer was allotted, plus Rs 1 lakh for a male worker, Rs 2 lakh for each woman and child, and Rs 3 lakh for transgender persons or women and children involving extreme cases of deprivation, sexual exploitation and trafficking, based on the discretion of the district magistrates.

The bottleneck

The bottleneck exists in two areas. First, is in the lack of access that a high ranking officer, such as a district magistrate would have in getting information from distant areas of the country, from the farm sector and non-farm sectors, as well as from other sources. That information comes in from informants associated with local thanas. That brings the SHO back into the picture and that old circus of justice repeats itself.

The second is that the netas, who these senior officials report to, are not keen to make people realise how much filth exists within his constituency. Hence the district magistrates are quietly asked not to take such issues up with any level of exigency.

As is said, to treat a disease, you must accept that you are sick. Only then would you go to a doctor and only then would the doctor take care of you. If the political parties are more worried about their image before the electorate, rather than address an age-old problem, then the meek have no chance of ever taking over the world, not in India.

Then you arrive at the final hurdle, the disbursement of funds. It is one thing that the hapless had been identified and rescued. It is another thing that they are all provided with a certificate saying they were bonded labourers. That does not happen. Which means even the meagre Rs 30,000 due to them does not come through. What is a rescued bonded labourer supposed to do, if the government refuses to even hand over this miniscule amount? Sometimes this happens even after the labourer has been given a release certificate.

These are people who had been tortured, dehumanised and oppressed for years. It is the duty of the government to take care of them. Instead, most are told that it is enough that they have been released from the clutches of evil, and you are the one who should manage the rest. You are on your own. As usual, no court, no lawyer, would come forward on their own accord, no part of the crumbling justice system will show sympathy.

Bonded labourers in India now exist even out of bondage, subservient to political bosses, waiting for scraps that never come their way.

Bonded labour in India: legal status

- Article 23 of the Constitution of India bans trafficking in human beings and forced labour, but a legislation defining and banning bonded labour went through Parliament only in 1976.

- The first countrywide survey to assess the nature and magnitude of bonded labour was undertaken in 1978.

- Subsequently, the Supreme Court of India pronounced a number of judgments to clarify the meaning of the term “bonded labour”. It has also appointed commissioners to the court and has given a number of directives to central and state governments to indicate the incidence of bonded and forced labour and to vigorously implement the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976.

- Since 1997, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has been given a pivotal role in monitoring the implementation of the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act and in ensuring that the directives of the Supreme Court are followed by the central and state governments.