By Sujit Bhar

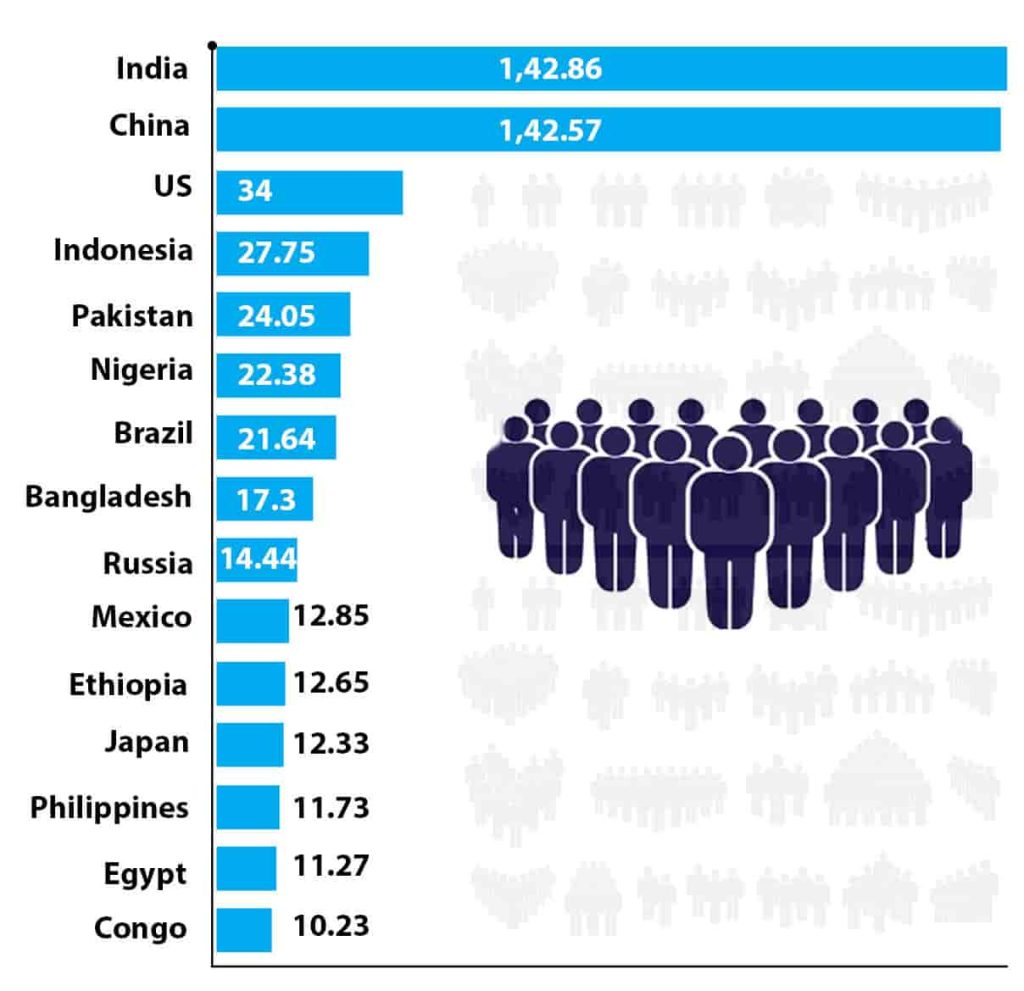

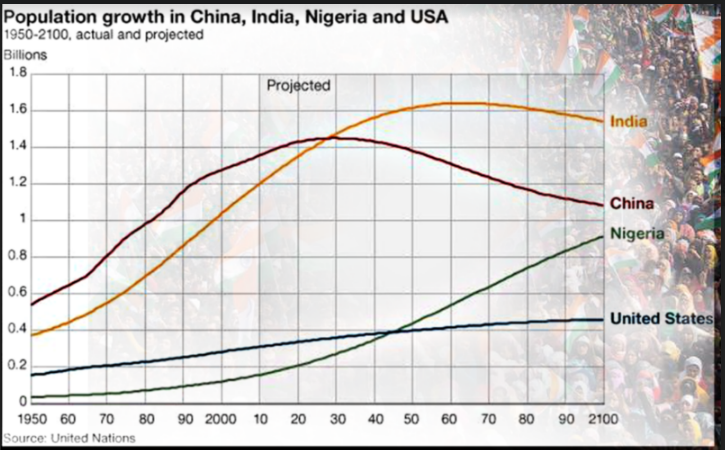

In mid-April, the UN Population Fund predicted on its World Population Dashboard that by July 1, India would cross China’s population by at least 3 million people, though everybody knew that this probably happened way back in January itself. This item of news was greeted with diverse comments, some castigating the family planning department for sloppy work, while others cheering this as an “achievement”.

Frankly, the country is yet to make up its mind on whether this will result in a bigger demographic dividend, as Indians have been told for the last decade-and-a-half, or cascade into unalloyed disaster. “Experts” have been quoted as saying that it will be a great thing if the government treats this as an opportunity, but so far such “expert” advice has failed to yield the desired results.

There is a problem with such comments. India has held on to this so-called demographic dividend for far too long to be able to boast about it. On the ground, little has changed. The poor have become poorer, education has fallen behind, the skilling rate has gone down and the overall state of affairs is worse today than it was a decade back.

The job scenario

Jobs are what India needs. As a McKinsey report says, India needs to create at least 90 million jobs by 2030. To do that India needs to grow at double its current GDP growth rate. With world economies slowing down, this is a difficult ask, despite recent export growths.

The 90 million mark is daunting. The report says that 60 million new workers are set to enter workforce, plus 30 million could move from the farm sector to others. Hence, the farm sector looks already overburdened. Also, to achieve all that, net employment would need to grow by 1.5% per year. Growth has happened, and is happening, but the pace is way below expected levels for an India-size population.

That population growth remains unabated, beating China, which is three times India’s land mass.

Women in the dark

The overall scenario also sees major disparities in growth. The participation of women in the labour force, for example, remained at abysmal levels and their education levels have fared no better.

India Development Review notes that while this stark gender disparity in India’s workforce has been well-documented, “there has been little by way of meta studies that examine public policies, programmes, data, and research across various parameters to motivate a better understanding of why female labour/workforce participation (FLWP) in India is so poor, and what can be done to change this.”

An NSSO PLFS (National Sample Survey Office’s Periodic Labour Force Survey) data of a couple of years back says that FLWP has actually worsened, hovering around only 17.5%. This compares poorly to the 55.5% of male participation in the labour force. Studied carefully, though, even this dataset has holes in it. That is because it seems to disregard the immense amount of work done by women in the fields of agriculture.

So, what seems to be the problem here, if the actual female participation is found to be more? It is the abysmal rate of remuneration to the women, if at all, that comes out as a complete farce.

The wage difference

What is the difference in wages? It is common knowledge that wages for similar work in India are significantly lower for women compared with those of men in both rural and urban India. Studies have seen this gap widen in rural areas over the last decade. These are official survey findings of the National Statistical Office in a report, Women and Men In India 2022.

On an average, across states (the rates vary) women earn about 32% to even about 50% less than a male for the same work in rural areas. The wage differential is a little better in cities. With passing time, this gender divide in wages seems to have increased.

These two critical issues—the abysmal participation of women in the labour force and the massive wage difference—have barely helped women in the country come out into open from their stifling existence in front of chulas at home.

And while we are aiming to replace China and Vietnam as the country of preference for labour-intensive industries, available data does not paint a pretty picture. In China, a World Bank report had said, female participation in the labour force decreased from a massive 63.98% in 2010 to 60.57% in 2019. Even with this decrease, it remained higher than the global female labour force participation rate of 51.26% in 2019.

The comparative figure for Vietnam was 73% in 2014, having come down to 68% in 2021. The 2021 figure for South Korea was 53.39%.

The productivity issue

It is not just the issue of labour participation; the other more important problem is one of productivity. According to the Ministry of Labour and Employment, within the Asian Productivity Organization (APO)— study period 2000 to 2013—labour productivity growth was highest in China at 9%, while India, though third in the region, was almost half, at just 5.2%. Even Mongolia, at 5.5%, was ahead.

The reasons for this weakness have been identified with poor infrastructure, excessive regulation, severe capital constraints and an inadequate supply of highly trained workers. A basic work culture also seems to be at play here, or how can Mongolia beat India on the productivity scale?

And while on the issue of training, or re-skilling, there has been some really bad news. According to the Ministry of Statistics & Programme Implementation’s Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), deep-rooted social norms and strictures have constrained the impact of many government policies. These effectively challenge their effective implementation.

A recent PLFS has been quoted in a report, saying that 51.5% of women who received vocational/technical training were quickly found to be out of the labour force and 10% remain unemployed. This is an indication that families have restricted any opportunity of economic freedom for the womenfolk.

This has had a worse side effect. About 54.8% of employed women landed in the informal sector, limiting their access to decent work and benefits.

Beyond statistics

There are the basic statistics of the current dire situation the country is in today. The largest employer in the country, after the agricultural sector, is the MSME sector, within which well over 95% is employed by the micro sector, a segment that remains permanently neglected, cash strapped and, hence, completely disorganised.

To pull a people out of poverty and utilise the so-called demographic dividend, it is essential that the small scale sector is invested in and developed. It is essential that, along with cheap loans, there should be a certain percentage of government contracts that are made available to these sectors. There has been an effort to this end, but it has proved to be too little, too late. Also, there should be enough hand holding and all financial institutions, including banks, should be sensitised to this end.

Also, considering the education levels of unskilled and semi-skilled workers—the maximum number among them being very poor—the manufacturing sector should gain more importance. According to the government’s Nivesh Mitra, the manufacturing MSMEs of India contribute around 6% to the country’s GDP, 33% to the manufacturing sector and 45% to exports. With around 361.76 lakh registered and unregistered MSMEs in the country (and this is a modest estimate), the sector provides employment to 805.24 lakh people, making it the second largest employer in India after agriculture sector.

Nivesh Mitra also says that out of total registered MSMEs in India, 67% are manufacturing SMEs while the rest are in the service sector. Besides providing wide range of services, the sector is also engaged in manufacturing of over 6,000 products from traditional to hi-tech items.

These data sets are not new. These were the projections well ahead of the current decade, and the projections also showed that timely intervention could have yielded results by now, even with the devastating effect of the Coronavirus pandemic coming in between.

The more things change…

Once you have come out of the confusing sea of statistics, you realise that you probably never realised how the world has changed outside, even how the demography of the country was changing. Political parties and their leaders were busy finalising their poll strategies and in making sure that the next five years were theirs, while, in the process, the so-called dividend that a young population had given the country sat rotting in silos, pushing down the productivity rate, increasing unemployment and creating an ever growing gender divide that tore society apart. It was like the old saying, “the more things change, the more they remain the same”.

To rubber stamp population growth as an achievement would be obtuse, to say the least. Population management is a complex matter. While numbers among the older generation will grow through the huge advances in modern medicine, it will be essential to know that just a stagnating mass of young people does not necessarily add to the productivity of a country.

When the productivity of the country is low, when the participation of women in the labour force is abysmal, when basic infrastructure is negligible in many parts of the nation, when government control is overbearing, when taxes are too many and when politics is the main preoccupation of the administration, chaos will rule.

It is given that India has the potential. But this knowledge has been around for ages. Unless potential energy is transformed into kinetic energy, and till such time that all available hands, male and female, join to give our country a productivity rate that the world has come to know from China, Vietnam, South Korea and such other countries, this population growth will remain a curse. It will breed disenchantment, crime, lethargy and even a complete breakdown of the social fabric as we know it.

—The author writes on legal, economic and corporate issues, apart from social commentary. He is Executive Editor at India Legal