By Sanjay Raman Sinha

A spate of verdicts and observations in recent times has put the spotlight on cruelty in marriages. Many a marriage has hit the rocks after a spouse faced the brunt of mental or physical violence.

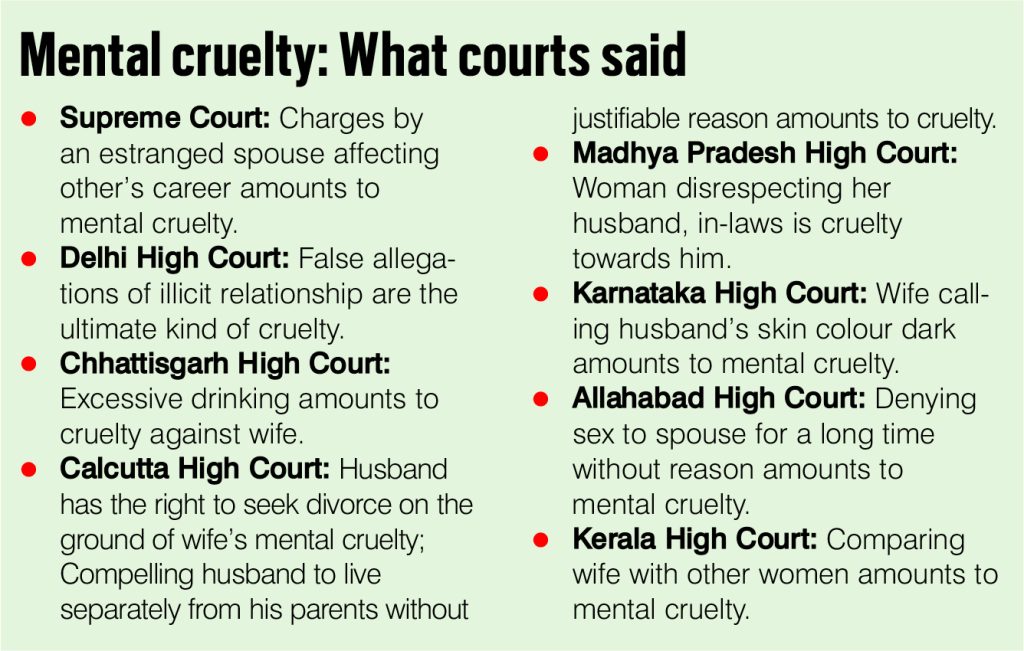

The Delhi High Court recently observed that “persistent insistence” of a wife to live separately from her husband’s family without a justifiable reason “can only be termed as an act of cruelty”. The bench ordered the dissolution of the couple’s marriage on the ground of “cruelty and desertion” under the Hindu Marriage Act. In another case, the Delhi High Court put an end to a couple’s decade-old marriage, saying that no law gives a husband the right to beat and torture his wife merely because they have married. The Supreme Court also observed in a recent judgment that keeping the parties together despite an irretrievable breakdown of marriage amounts to cruelty on both sides.

Marital discord festers like a sore and manifests itself in diverse ways, mental cruelty being one of them. The physical forms of cruelty easily manifest themselves, but mental cruelty is more subtle and unbearable. It corrodes the psyche of the oppressed party and leaves the marital relationship in tatters.

Recognising its detrimental effects, the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, Section 13 (1) (ia) allows both the wife and the husband to seek divorce on the grounds that their spouses subjected them to cruelty after marriage.

The Section says: “Any marriage solemnised, whether before or after the commencement of this Act, may, on a petition presented by either the husband or the wife, be dissolved by a decree of divorce on the ground that the other party (ia) has, after the solemnisation of the marriage, treated the petitioner with cruelty.”

Cruelty herein includes both physical and mental. Mental cruelty is a penal offense under the IPC. Section 498A of the IPC punishes the husband or any relative of his who subjects a woman to cruelty. Cruelty includes actions which are likely to make a woman commit suicide or cause her grave injury or endangers her life. Harassment of a woman or any of her relatives to meet any unlawful demand for money, property or any other valuables is also included in the clause. This Section was specially introduced in 1983 to check the menace of dowry-related and other marital violence against women.

There is no similar provision in law that provides for cruelty against men by their wives. The Supreme Court has, in many instances, stressed that men are equally susceptible to cruelty in matrimony as their women counterparts. The spouse can seek divorce on this basis. The Court has also defined the test to decide whether a person’s behaviour amounts to cruelty. It held that it is incumbent to decide not only on the basis of whether an act would seem cruel to a person of normal sensibilities, but essentially to see what effect it would have on the aggrieved spouse who is before the court. This is because what may be cruel to one person may not be cruel to another.

So cruelty is conditional. The person alleging cruelty only has to prove that the spouse’s behaviour created an apprehension that it would be harmful to them to continue living with that person. Mental cruelty is hard to define and can include the following situations: Humiliating the husband/wife in front of his family and friends, undertaking the termination of pregnancy without the husband’s consent, making false allegation against the spouse, denial of physical relationship without a valid reason, constant demand for money, aggressive behaviour of spouse, etc. The law recognises such cruelty as a ground for the husband to seek divorce as well.

Incidentally, except for Uttar Pradesh, no other state has made any amendment in Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act so as to have cruelty as a ground for divorce. It was in 1976 that Parliament by its Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act amended Section 13 of the Hindu Marriage Act to make cruelty also a ground for divorce. This happened after an amendment in 1976, which allowed both divorce and judicial separation. In this case, the wife wrote a letter to the employer of her husband imputing false allegations. The court had held that this action constituted cruelty under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. “The brutality is physical as well as mental. If wrong the allegations will inflict mental suffering to the accused,” the bench held.

By this amendment, Section 10 of the Hindu Marriage Act was also amended in a manner that instead of giving distinct grounds for judicial separation, a scheme was formulated that a petition for judicial separation could be made on any of the grounds for divorce specified in sub section (1) of Section 13. Hence, now the same grounds are available for judicial separation as well as for divorce. After the 1976 amendment, the ground of cruelty for judicial separation as well as for divorce became: “(i) has, after the solemnization of the marriage, treated the petitioner with cruelty’’.

The scheme liberalised the provisions relating to judicial separation and divorce. Now it is not incumbent to prove that the respondent had repeatedly treated the petitioner with cruelty. Further, the petitioner has also not to prove that he/she was treated with such cruelty as to cause a reasonable apprehension in his/her mind that it will be harmful to him/her to live with the other party.

Clearly now as the modified law stands, mental cruelty must be of such a nature that the parties cannot reasonably be expected to live together. Mental cruelty need not be proved to be such as to cause danger to the health, limb or life of the petitioner. Mental cruelty now bears the same weight as physical abuse, audio and video evidences and witness testimonies.

At a time when marriages are under strain due to mental and physical cruelty of one spouse on another, the Domestic Violence Act which penalises men on grounds of harassment has increasingly become a tool of persecution on false grounds used maliciously by wives. This was stated in no uncertain terms by the Calcutta High Court recently.

In another case, the Calcutta High Court issued a slew of directions, including no automatic arrest of the accused in domestic violence cases. The Court ordered that police officers are directed “not to automatically arrest when a case under Section 498-A IPC is registered but to satisfy themselves about the necessity for arrest under the parameters laid down above flowing from Section 41 Cr.P.C”. This proves the flip side where penal provisions meant to protect women are maliciously used by them.

Courts and lawmakers have now recognised this fact and created provisions for legal remedies. But this is essentially a social malaise and legal action is the last recourse, often at the cost of marriage.