The large number of unfilled vacancies in the courts is a symptom of a widespread systematic malaise in which the Executive and the Judiciary must share equal blame as the crisis escalates

~By Inderjit Badhwar and Sujit Bhar

The graceless sparring between the Executive and the Judiciary over the appointment and elevation of judges, particularly in the upper echelons of the courts, exploded into new low-blows last week when a conveniently leaked letter from Justice Jasti Chelameswar (dated March 21) to the chief justice and 22 other Supreme Court brother judges hit the headlines. The judge, due to retire in a few months, is the second-most in seniority to Chief Justice Dipak Misra.

Many observers called this Part 2 of the “mutiny” within the Supreme Court, which broke out on January 12 as a press conference was held at Justice Chelameswar’s house. Joined by Justices Ranjan Gogoi, Madan Lokur and Kurian Joseph—who form the Supreme Court collegium that appoints judges—the foursome levelled a direct frontal assault on the chief justice of India (CJI) for allegedly assigning case rosters in an ad hoc fashion.

The subliminal message was that the CJI was indirectly catering to the wishes of the Executive and assigning cases to judges who may be more favourably inclined to the views taken by the ruling political party on national issues under litigation, among them Aadhaar and the right to privacy, the upcoming Ayodhya case and the controversial death of CBI special judge Brijgopal Harkishan Loya.

The latest salvo calls for judicial unity in resisting what is being seen as another blatant attack on the Judiciary’s independence. It followed the Union government directly approaching the chief justice of Karnataka HC, Dinesh Maheshwari, to re-open an investigation against a subordinate judge. “The Chief Justice of the Karnataka High Court has been more than willing to do the Executive bidding, behind our back,” Chelameswar wrote. The probe has reportedly been withdrawn.

The principle at stake appears to be that Justice Misra, when he found he was being bypassed, should have taken the initiative to raise the initial hue and cry in defence of the independence of the collegium and the Judiciary.

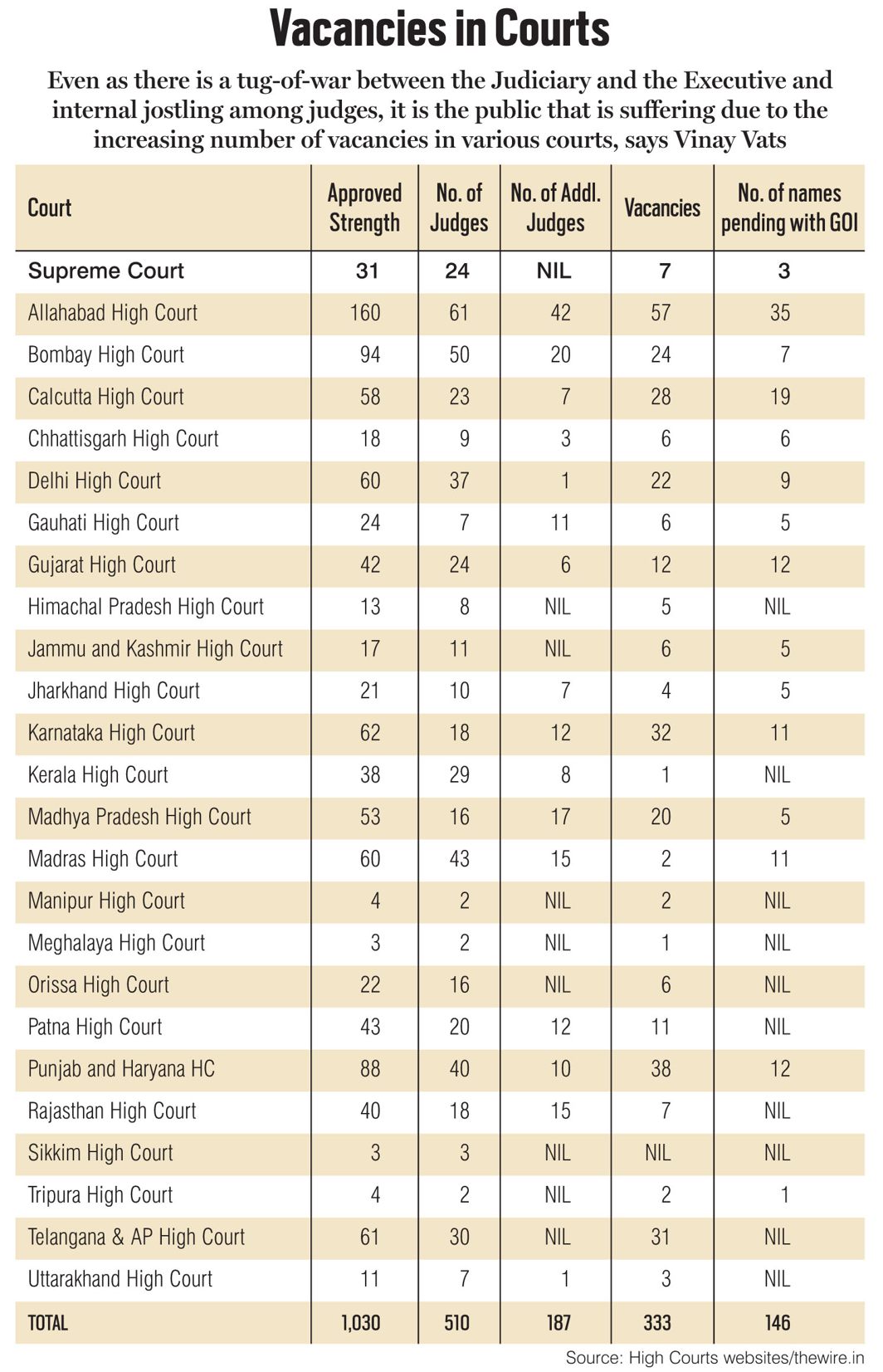

Legal luminaries India Legal spoke to are of the opinion that a definite finding can be made to support the case that the Executive is, indeed, interfering, often quite shabbily in the affairs of the Judiciary and politicising it. One result is the staggering number of appointments (see box) recommended by the collegium which are gathering dust in the files of the Union government, particularly the law ministry which is supposed to forward such recommendations to the president for what is usually a routine approval.

To be fair to the Executive, it may, perhaps have a defence in the Karnataka case, which has been cited, because there have been prior inquiries against the judge. But what about other high-profile recommendations by the collegium which are simply being ignored? Two recent examples are the recommendation of the collegium for the elevation of Uttarakhand High Court Chief Justice KM Joseph, and senior advocate Indu Malhotra as apex court judges.

Malhotra would be the first woman lawyer to be directly appointed as a judge of the top court, instead of being elevated from a high court. She would be the seventh woman judge in the apex court since Independence.

Malhotra would be the first woman lawyer to be directly appointed as a judge of the top court, instead of being elevated from a high court. She would be the seventh woman judge in the apex court since Independence.

Justice Joseph shot into prominence in 2016—much to the discomfiture of the ruling BJP—when a high court division bench, headed by him, nullified imposition of President’s Rule in Uttarakhand. While Justice Joseph’s future hangs in the balance, Malhotra has resumed private practice.

While India Legal has been persistent and consistent in fighting for a Judiciary free of Executive interference and control, the magazine has frequently also been critical of the Judiciary when it has made itself vulnerable to even the appearance of manipulation.

Perhaps the most blatant case in recent years was that of Karnataka senior judge Jayant Patel. Just before his timely elevation as chief justice was due —and he was found qualified even for a Supreme Court position—he was summarily transferred to Allahabad High Court in a decision made by the collegium, over which he resigned in disgust. This was not the first time. This was the same judge who had ordered a CBI probe in the “fake encounter case” case of Ishrat Jahan when he was at the Gujarat High Court.

Then, too, he was transferred to Karnataka just before his promotion as chief justice was due. On both occasions, powerful associations in Gujarat and Karnataka threatened agitations and openly accused the collegium of bending before the wishes of the Dilli Durbar.

As one senior lawyer put it: “One cannot use double standards. After all, Justice Chelameswar was very much in the Supreme Court then. Why did he not talk about the independence of the collegium then? And who were the judges who voted against the majority bench of the Supreme Court which ruled that the formation of the NJAC to replace the collegium was unconstitutional?”

Very often, personal prejudices override compulsions of merit in the appointment and elevation of judges. Iconic judge AP Shah, former chief justice of the Delhi High Court and Law Commission chairman, could not make it to the Supreme Court because of personal opposition from Chief Justice SH Kapadia.

Another lawyer of eminence, Gopal Subramaniam, who was also headed for the Supreme Court along with Rohinton Nariman, AK Goel, and Arun Mishra, was stopped dead in his tracks by a blizzard of bad publicity engineered in the press about him by the Executive branch. Subramaniam threw in the towel: He asked his name be withdrawn rather than face what his supporters say was a dirty tricks campaign. These same supporters also secretly wonder whether the collegium could have been more active in championing his cause.

The Impeachment Conundrum

The move to impeach Chief Justice Dipak Misra has been partly designed by the Opposition, especially the Congress, to keep pressure on him even as critical issues such as Ayodhya, Aadhaar and the Loya case are still being adjudicated. It is also a counter tactic to ward off the Executive’s continuous pressure and interference in the apex court

In a democracy like India, it is very important to maintain the independence of all three pillars of governance, especially of the Judiciary. In this regard, the removal of a judge from office should be done without any bias coming into play. If the Executive has the power to remove a judge easily, then it will raise serious questions about the independence of the Judiciary and will become subject to the control of the government.

A judge can be removed from office by an order of the president of India only on grounds of “proved” misbehaviour or incapacity. The order can be issued following an address to both houses of Parliament. The address has to be supported by a majority of total members in each house and also by a majority of not less than two thirds members of each house present and voting.

The word “proved” has special significance as an address can be presented only after an alleged charge of incapacity or misbehaviour is investigated, substantiated and proved by an impartial tribunal. This tribunal has not been mentioned in the Constitution and it was left to Parliament to lay down a law to investigate and prove charges against a judge. The Parliament, therefore, enacted the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968, which regulates the procedure for investigation into allegations of misbehaviour or incapacity of a Supreme Court judge.

COMMITTEE OF INQUIRY

The procedure followed under this law is that a notice of motion is given by a minimum 100 members of the Lok Sabha or 50 members of the Rajya Sabha. Then the speaker or chairman of the house has the power to either refuse it or admit the motion. If the motion is admitted, the speaker has to constitute a committee of inquiry which will consist of a Supreme Court judge, a chief justice of a High Court and a distinguished jurist. Further, if the notice for motion is presented in both houses on the same day, then the committee of inquiry has to be constituted jointly by the speaker and the chairman.

The committee of inquiry first frames the charges against the judge and then an investigation is proposed. The judge is given a reasonable opportunity to be heard, including cross-examination of witnesses. If there is physical or mental incapacity of the judge, then the inquiry committee has to arrange for his medical examination by a medical board appointed by the speaker or chairman of the house.

The report prepared by the committee is then presented to the concerned house. If the committee lays down the charges levelled against the judge, then no further action is taken on the motion of his removal. However, if the committee finds that the accused judge is guilty of misbehaviour or is suffering from any incapacity, then the house can consider the motion.

Then the house has to adopt the procedure laid down in Article 124(4) of the Constitution as enunciated above.

—By Vinay Vats

While there are those who openly praise Justice Gogoi for his role in the “four-judge mutiny” in which they expressed their strong dissent against the behaviour of the Court, others contrast this with Justice Gogoi’s treatment of Justice Markandey Katju, a former Supreme Court judge, who in an unprecedented move, was served a contempt notice and summoned by a bench headed by Justice Gogoi because of his outspoken criticism of judicial behaviour in a controversial case.

The historical record in this battle for the benches has been a mixed one with some judges folding before the Executive and others fighting back. Justice Ajit Nath Ray was the lone dissenting judge among 11 judges who scrutinised the constitutionality of the Bank Nationalisation Act of 1969. The government was nationalising 14 major private banks. In August of that year, he was appointed judge of the Supreme Court. But surprisingly, when it came to the appointment of the Chief Justice of India in 1973, he superseded senior judges, Justices Jaishanker Manilal Shelat, AN Grover and KS Hegde. That was viewed as an attack on the Judiciary and the incident has not been washed away with time. There were protests and former Chief Justice Mohammad Hidayatullah had commented that “this was an attempt of not creating ‘forward looking judges’ but the ‘judges looking forward’ to the plumes of the office of Chief Justice”.

That was not the end of it. In 1977, Justice Beg superseded Justice Hans Raj Khanna. The Executive has grown more and more aggressive over the years and seeks out the weak ones to grab and convert. The collegium system wasn’t in place at that point, though.

India is one of the few countries in the world where judges appoint their own (though there is concomitant acknowledgement from the Executive). Is that a good thing or bad? In the US system, the Executive does, but each nominee goes through a Senate grilling that brings out to the public the judge’s innermost ghosts. This would be appalling in India.

The separation of powers envisaged by the Constitution leaves scope for osmosis, so each section has a handle on the other, addressing shortcomings across borders.

Introspection, therefore, isn’t restricted to any arm of a democracy. A display of unity by the Supreme Court and a diagnosis of its ailments—not in varying approaches to the law—but in defence of the independence and freedom of the Judiciary, is a cause that is noble and essential to safeguarding this Republic. But the physician, too, must be involved in the process of healing himself.

Collegium: The issue of transparency remains uppermost, say luminaries

The Collegium issue and the huge disconnect with the executive regarding this has put the Supreme Court in a front it might not have wanted to be in. India legal asked several legal luminaries for their comments in this regard. The legality, or at least the fairness of the Collegium system, remained a question on the basis of the lack of transparency in this system, and the possibility of nepotism and favouritism.

The following are some of the comments:

JUSTICE V K MATHUR (Former Judge of Allahabad High Court)

The landmark judgment of the Supreme Court, in the matter of Advocates-on-Record v. Union of India, overruled the earlier judgment in the S.P. Gupta’s case, which provided supremacy to the executive. It was held by the CJI will consult two senior most judges and take their opinion. Thus the role of executive was made a mere formality. As the term consultation was not clarified, therefore different interpretations were drawn. Later in 1998 through yet another judgment clarifying the term emphasis was laid upon the requirement of effective consultation with senior judges.

The landmark judgment of the Supreme Court, in the matter of Advocates-on-Record v. Union of India, overruled the earlier judgment in the S.P. Gupta’s case, which provided supremacy to the executive. It was held by the CJI will consult two senior most judges and take their opinion. Thus the role of executive was made a mere formality. As the term consultation was not clarified, therefore different interpretations were drawn. Later in 1998 through yet another judgment clarifying the term emphasis was laid upon the requirement of effective consultation with senior judges.

The stand taken by the judiciary for establishing a Collegium was criticised for being non-accountable and undemocratic. The balance of power provided under Art. 124(2) and Art. 217(1) of the Constitution was disturbed. The NJAC Act was declared unconstitutional and judicial accountability commission was challenged on the ground of violation of basic structure. The Collegium system lacked transparency and accountability. One of the major criticism is that in appointments nepotism and favouritism was practised.

Recommendations for the vacancies were not made promptly resulting shortfall in judge strength. However, the recent decision of Supreme Court to disclose the minutes of collegium regarding recommendations and rejections and holding of interaction with candidates are welcome steps. The solutions in evolving a transparent, accountable and timely selection by a body consisting of judges, representatives of executive and eminent jurists.

To bring transparency applications may be invited from eligible candidates from the bar and the applications after scrutiny may be shortlisted. Every incumbent should be asked to participate in either group discussion or interactive sessions and suitable candidates may be summoned for final round of selection before the collegium.

JUSTICE BHANWAR SINGH (Former Judge of Allahabad High Court)

The Supreme Court decision on Collegium system is a welcome one. However, only uploading the procedure for collegiums system in the website will not suffice the need of the hour. This kind of mechanism for adopting transparency in the Collegium system will further increase more problems. The main problem lies with the Collegium system itself and the act of National Judicial Commission has also confirmed it. Supreme Court rule regarding transparency in collegiums system and its online publications will have serious repercussion.

The Supreme Court decision on Collegium system is a welcome one. However, only uploading the procedure for collegiums system in the website will not suffice the need of the hour. This kind of mechanism for adopting transparency in the Collegium system will further increase more problems. The main problem lies with the Collegium system itself and the act of National Judicial Commission has also confirmed it. Supreme Court rule regarding transparency in collegiums system and its online publications will have serious repercussion.

If we go in-depth, then the Supreme Court decision might have come up as a result of government’s objection regarding non-transparency in the Collegium System.

According to me, there can be other mechanism regarding adopting of transparency apart from publishing it in the website, because this will increase complication.

JUSTICE A N MITTAL (Former Judge of Allahabad High Court and current Chairman of the UP Law Commission)

I’m in favour of transparency in judicial appointments. There have been various drawbacks in present Collegium system which were even accepted by the Hon’ble judges during the hearing of judicial appointment commission case.

I’m in favour of transparency in judicial appointments. There have been various drawbacks in present Collegium system which were even accepted by the Hon’ble judges during the hearing of judicial appointment commission case.

The MoP should be finalized at the earliest in the interest of litigants as well as country. To bring more transparency in the working of high courts, the old system of transferring the newly appointed Hon’ble judge from parent high court to some other high court is also necessary so that the allegation of generating litigation for their sons/daughters, and relatives as well as allegation of face value favourism may also be avoided

—India Legal Bureau