By Advocate Vikas Bansal

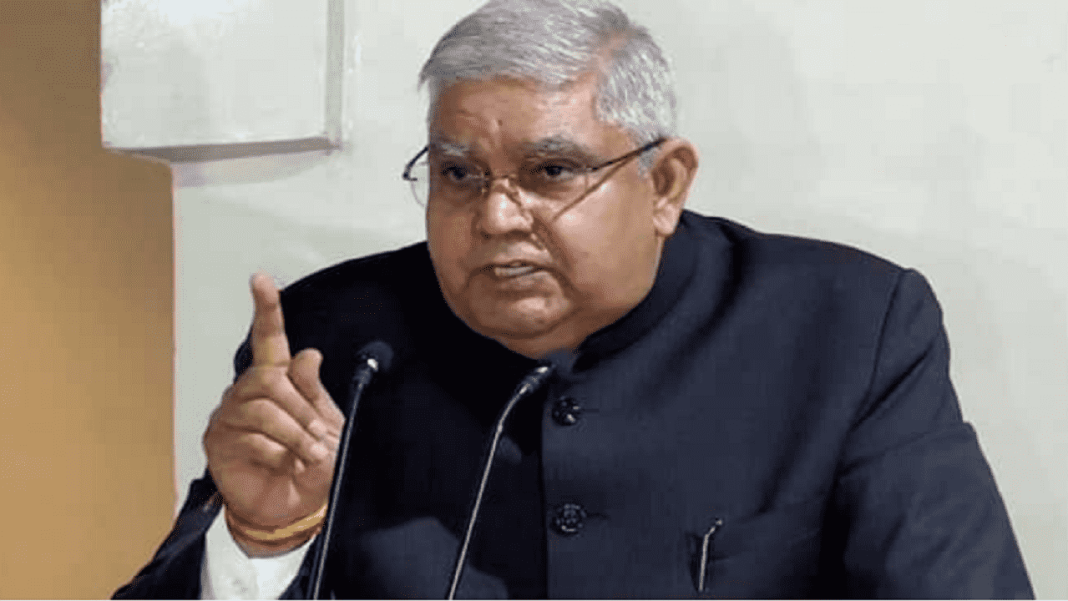

The ongoing tussle between West Bengal Governor Jagdeep Dhankhar and the Mamata Banerjee government – specifically, the West Bengal Legislative Assembly and the council of ministers – was poised to spill over into a full-blown crisis with Governor Dhankhar’s tweet on Saturday.

The tweet had a letter which said he had decided to prorogue the Assembly under his Constitution-given powers. With reports talking of a constitutional crisis, the Governor clarified in a tweet an hour later that it was done at the recommendation of the West Bengal government to defuse rumour-mongers.

Proroguing an assembly is discontinuing, without dissolving the House. The Governor, in his letter, cited that his powers come through Article 174 of the Constitution of India. This act was unprecedented, and the question was whether the powers have been justly used or misused. It is well-settled law that a Governor can use his discretionary powers given or envisaged in Article 174 of the Constitution, under reasonable circumstances.

In his first tweet of the day Governor Dhankhar wrote; “In exercise of the powers conferred upon me by sub-clause (a) of clause (2) of Article 174 of the Constitution, I, Jagdeep Dhankhar, Governor of the State of West Bengal, hereby prorogue the West Bengal Legislative Assembly with effect from 12 February, 2022.” An hour later he posted another Tweet, stating; “WB Guv: in view of inappropriate reporting in a section of media it is indicated that taking note of govt recommendation seeking proroguing of assembly, Guv in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Article 174 (2)(a) the Constitution has prorogued WBLA w.e.f. Feb 12,2022.”

So, what are the powers of a Governor, under the Constitution?

The powers of a Governor is defined in Article 174 of the Constitution of India, which deals with the power to summon, prorogue and dissolve an assembly. Under Article 174, a Governor shall summon the House at a time and place, as she or he thinks fit. Article 174 (2) (a) says a governor may from “time to time” prorogue the House and 174 (2) (b) allows her or him to dissolve the Legislative Assembly. Article 163 of the Constitution defines the scope where the Governor may exercise certain functions at his discretion, as provided in Article 163(1). The first part of Article 163(1) requires the Governor to act on the advice of his council of ministers. There is, however, an exception in the latter part of the clause in regard to matters where he is, under the Constitution, required to function at his discretion. The expression “required” signifies that the Governor can exercise his discretionary powers only if there is a compelling necessity to do so. These two articles, read together, explain the scope of a Governor’s powers.

Nabam Rebia judgment of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court, in its recent judgment in Nabam Rebia case (2016), settled the question of a Governor’s discretion and the ‘scope’ of judicial review over the governor’s functions. The five-judge Constitution Bench had held that “a governor can summon, prorogue and dissolve the House, only on the aid and advice of the council of ministers.” This explains the West Bengal Governor’s second Tweet. In that case, the Apex Court had clarified that if the Governor had reasons to believe that the chief minister and her or his council of ministers have lost the confidence of the House, a floor test could be ordered. Instead, it seems the Governor acted in a manner opposed to the rule of law and therefore, arbitrarily and in manner that certainly surprises “a sense of juridical propriety.” That case had stemmed from a constitutional crisis in Arunachal Pradesh, which emerged when the Governor had advanced the 6th session of the Legislative House from 14/01/2016 to 16/12/2015, by his order dated 09/12/2015, allegedly without the aid and advice of the council of ministers and the Chief Minister, and had listed the removal of the speaker on the agenda, which constitutes the foundation of challenge by Speaker Nabam Rebia.

Plea moved in Calcutta High Court seeking removal of Governor Jagdeep Dhankhar

Recently, a plea has been filed in the Calcutta High Court seeking directions to the Central government to remove Jagdeep Dhankhar, Governor, West Bengal, claiming that he was acting as the “mouthpiece of the Bharatiya Janata Party”. The plea alleged that he is bypassing the State council of ministers and is dictating directly to State officials which is violative of the Constitution. Petitioner relied on B.P. Singhal v. Union of India, wherein the Supreme Court observed: “A Governor is neither the employee nor the agent of the Union government. It had been further observed that like the President, Governors are expected to be apolitical, discharging purely constitutional functions irrespective of their earlier political backgrounds.”

Further, in case Rameshwar Prasad Vs. Union of India, wherein the Supreme Court had recognised that the Governor was not excused from judicial review simply because he enjoyed such immunity under Article 361 of the Constitution: “Immunity granted to the Governor under Article 361(1) does not affect the power of the Court to judicially scrutinise the attack made to the proclamation issued under Article 361 (1) of the Constitution of India on the ground of mala fides or it being ultra vires”

Prorogation held to be invalid, in United Kingdom, in case of R Vs Prime Minister by a full bench of 11-justices Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United Kingdom on the September 24, 2019, had ruled unanimously that prorogation was both justiciable and unlawful, and therefore null and of no effect. The court found that British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s advice to Queen Elizabeth II to prorogue Parliament “was outside the powers of the Prime Minister”.

The decision came in the case of “R Vs Prime Minister” where the British Prime Minister advised the Queen to prorogue the Parliament. The UK Supreme Court had held, “The Court is bound to conclude, therefore, that the decision to advise Her Majesty to prorogue Parliament was unlawful because it had the effect of frustrating or preventing the ability of Parliament to carry out its constitutional functions without reasonable justification.”

This reference becomes necessary in the light of the fact that the Indian Constitution was drafted with the shape and substance of existing laws in the UK in mind, and with adaptations. Keeping these in mind, Governor Dhankhar’s second tweet gains importance. If the government’s council of ministers had, in fact, made this request to the governor, his act was correct. If not, there would have been a court case in the offing.

Advocate Vikas Bansal is a practising advocate in the Supreme Court of India.