By Prof Upendra Baxi

Every constitutional democracy faces the question of reconciling the demands of pubic security and order as a collective human right on the one hand and the freedom of individuals to protest peacefully on the other. Sooner or later, constitutional courts have to face the daunting task of interpretation of conflicting rights.

The Supreme Court of India has, in a long line of decisions, struggled to articulate the frameworks of reconciling the rights in conflict and in the specific contexts of adjudication. It recently upheld peaceful protest in non-belligerent occupation of certain public spaces as a vital aspect of a dynamic democracy always in ferment. And the police authorities are to act professionally, though with constitutional care and concern.

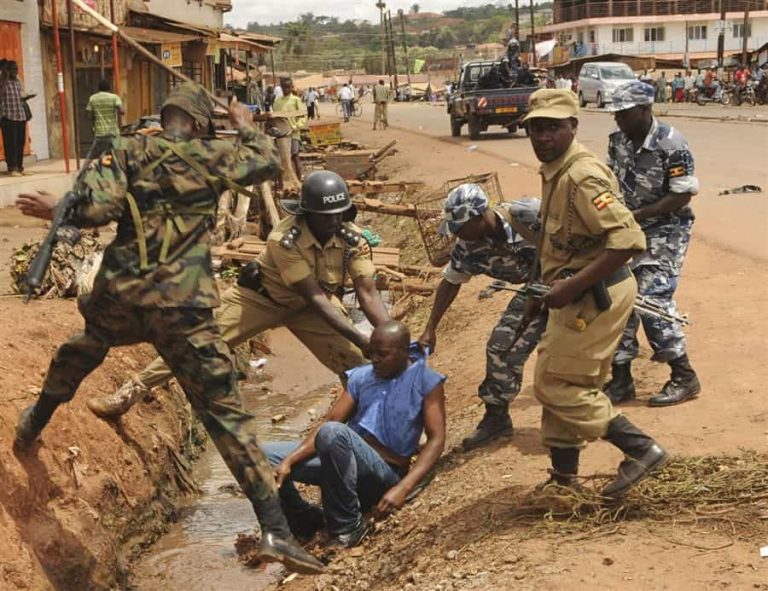

The Ugandan constitutional courts have handled similar questions. In Muwanga Kivumbi (2005), Section 32(2) of the Police Act was declared unconstitutional and this was upheld in a 2020 decision invalidating Section 8 of the Public Order Management Act, 2013 (POMA). This law rearticulated supremacy of police powers to maintain security and law, downgrading the right to peaceful assembly in public spaces. It is interesting at the outset to note the social identity of some of the social action petitioners.

Before the Court of Appeal were respectable groups of proud Ugandan citizens—Human Rights Network Uganda, the Development Network of Indigenous Voluntary Associations and the Uganda Association of Female Lawyers whose democratic agenda led them to argue that parliament may not enact a law invalidated by the apex court. Section 92 of the Ugandan Constitution says—and this may sound quaint to Indian constitutional ears—that “Parliament shall not pass any law to alter the decision or judgment of any court as between the parties to the decision or judgment”. Narrowly construed, POMA did not have this effect in the instant case, but the High Court adopted the larger view that in substance, the nullified Section 32(2) of the Police Act was “reincarnated” by POMA.

The gravamen of the petitioners was that the Act places burdensome restrictions on an individual’s ability to exercise rights to hold public meetings, assemblies and processions and that it “grants the Inspector General of Police or any officers he/she designates absolute discretion and broad authority to stop, control and use force to disperse public meetings”. They are also “authorized to impose criminal liabilities on organizers and participants of public meetings”.

It was contended that “it would not be wise to assume that all persons in the exercise of their right to assemble and peacefully demonstrate” may not “actually do so strictly in accordance with the law”. Justice Cheborion Barishaki (for the 4:1 majority, March 26, 2020) carefully revisited the 2005 judgment and held that the legislative intention and effect demonstrated how POMA essentially, and impermissibly, overturned that decision.

Also Read: Supreme Court says OBC quota in Maharashtra local bodies shouldn’t exceed aggregate 50 percent

Indeed, the Court lamented the fact that parliament and the executive “contemptuously ignored” a judicially well-reasoned decision. Neither the “blatant disregard” nor the watering “down” of that decision is to be considered as constitutional acts. The learned Justice applauded the raison de etre, and the ratio of that decision which, in essence, held that while the “supervision of public order is a core duty of the police”, it cannot “be discharged by prohibiting sections of the public from exercising their constitutionally guaranteed rights to demonstrate peacefully or hold public meetings of any nature”.

Thunderously, the Court held: “Passing legislation that alters or undermines a judicial decision has dire implications for the future application of the checks and balances necessary for the functioning of a civilized democracy and prevention of peremptory behaviour by the three pillars of government, namely, the Legislature, Executive and Judiciary”. Further, the separation of powers doctrine is “the very core of Uganda’s growing constitutional governance” and it requires that “no room should be given to attempts to whittle down this growth and regress into the dark days of the political and constitutional instability”.

Incidentally, this last observation also briefly refers to the basic structure doctrine. When parliament considers a constitutional amendment, it may “trigger” some intractable constitutional questions concerning whether some or all human rights provisions “form part of the basic structure of our constitution”. The Indian doctrine of the basic structure did not entirely shipwreck on the shores of Uganda, but it did sustain an amendment allowing no age restrictions for imperial presidency.1 The Indian doctrine anyway has been adjusted to changing realities in Anglophonic African jurisprudence.

The Court articulates constitutional anxieties about police powers which tend to become “a tool” for “the … partisan purposes under the guise of preserving public order”. It directs the police as well as all constitutional authorities to always recall that the constitution is not a charter of the “abuse” of public powers, but rather an arena that preserves, promotes, and protects citizens’ fundamental public rights. Transcending the idea that these rights are given by the Constitution and can therefore be only taken away under it, the Court valiantly holds: “Public processions, meetings or gatherings, irrespective of whether they are of apolitical, religious or social nature are protected by the constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of expression, free speech and assembly. Peaceful public protests are equally protected by the constitution.”

Justice Kenneth Kakuru (agreeing with the majority) goes a step forward when he reiterates his own views in Mawandha, (2007): “It cannot be that, under the Constitution made by the people themselves, a law that curtails and criminalizes their freedom of expression, assembly, and conscience, would be valid.” His Lordship further emphasises “the duty of every government to listen to the voice of its people and to attend to their grievances, lest this Country returns to the dark days of the past”. He rules that all criminalisation of peaceful dissent is unlawful.

Justice Elizabeth Musoke (concurring) clarifies that the Court is not only authorised to hear such petitions, it is equally obliged to resolve the issues therein. This a refreshing acknowledgement, especially when considered in the light of the recent SCI tendency to regard Article 32 right to constitutional remedies as basically a source of discretionary power rather than a constitutional duty.

She also says that the judgments that stress the human right of assembly are crucial “commendable steps to consider … Uganda’s international obligations in the field of respecting human rights, including the right to assembly”. The learned Justice recalls the draft comments on the Convention on Civil and Political Rights which extol “common expressive purpose” of participants in a peaceful assembly… “conveying a collective position on a particular issue” and “asserting group solidarity or identity”. Assemblies may also serve other goals and still be protected because they have an “expressive purpose”. The POMA provisions are found “unduly burdensome”, specifically enabling “the authorities the powers to use criminal law to sanction citizens merely for wanting to exercise their right to assemble”.

Justice Stephen Musota was the lone dissenter to find the “wording of Section 32(2) of the Police Act…completely different from that of Section 8” of POMA. Instead of giving vast arbitrary powers to the police as the former did, the latter “standardized” police discretion. Moreover, particular acts under POMA can always be reviewed by constitutional litigation. Justice Musota held that the duty of the Ugandan police to maintain security, law, and order and also the right to assemble: “The constitution therefore recognizes” both “in equal measure”; and the POMA “facilitates the police in performing this duty”.

The mere fact of this being a solitary dissent does not affect its integrity. Dissent necessarily means the end point of a dialogue; and at times, the dissent of today speaks to the law of the future. But (with respect), this dissent is not among those that address a democratic future.

Surely, the Ugandan National Constitution of 1995 is distinctive in the elaboration of duties and functions of the national police (Articles 211-214). But Article 212 which details its functions nowhere lists among these either downgrading of dissent or adjudication of rights enshrined in the constitution! The stated functions of the police agencies do not extend to the maintenance of the integrity of rights structures under the constitution.

As security agencies, their main task lies in maintaining law and order, and not necessarily in developing human rights friendly policing cultures. Aside from the problems of delegation of vast discretionary powers, how is the police official to arrive at a “reasonable order” adjusting the conflicting rights? Are all rights to be considered equal or do basic rights have a threshold paramountcy over considerations of law and order?

Also Read: Encroaching village pasture land can invite both civil, criminal action, says Allahabad HC

The wider implications of the comparable Ugandan and the recent SCI decisions on core human and fundamental human rights await a more detailed consideration and critique.2

—The author is an internationally-renowned law scholar, an acclaimed teacher and a well-known writer

1 See Benson Tusasirw, “The Basic Structure Doctrine and Constitutional Restraint In Uganda: The “Age Limit” Case”, East African Law Review, 46z;1, 29-53(2019); KaroliSsemogerere, “ Uganda’sAge Limit Petition: Constitutional Court Demurs on Substance, Cautious on Procedure”, https://constitutionnet.org/news/ugandas-age-limit-petition-constitutional-court… (14 August, 2018)

2 Constitutional histories of Uganda and India vary sharply, and in many respects are not comparable. See, for example, for Uganda, Yoweri K. Museveni, Sowing the Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda, (London: Macmillan, 1995); and for India, Granville Austin, Working a Constitution: The Indian Experience, (Oxford University Press, 1991). Yet the resilience of judicial review powers in both societies is quite remarkable.